Abstract

(This paper takes stock of the economic challenges Pakistan is currently faced with. Ten areas are identified: scarcity of savings, low investment, limited availability of formal credit particularly to small and medium enterprises, low financial inclusion, dwindling FDI, low human capital, deficient and low-quality public infrastructure, regressive taxation structure, weak institutional quality, and stagnant exports. The key issues in the identified areas are discussed in the light of data and evidence. Comparison is also drawn with comparator countries on various accounts to highlight the issue of low national competitiveness. It is emphasized that constraints posed by the said economic factors have induced macroeconomic instability, further dampening the prospects of economic recovery. Summing up the discussion of the economic woes of Pakistan, this paper suggests that the creation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem would be required to put the country on the path of economic development – Author).

Increasing the size of GDP and wealth creation are important levers of prosperity. Sustained economic growth constitutes the minimum necessary condition for poverty reduction and well-being. One cannot directly see, or smell, or touch economic growth but it is in the newspaper headlines. It is in political debates. Economists and historians do research and publish books and papers on its determinants. IMF and World Bank forecast its short-term and long-term pace country-wise and for the globe. Despite its intangibility, it is omnipresent. It reflects itself in bricks and mortars, in schools, in hospitals, in kitchens, in health, in education and in overall wellbeing of the people though it tells little about the distribution of said things in the society1.

The growth story of Pakistan is a story of fluctuations, of ebbs and flows, of boom and bust cycles. It showed high growth rates during the 1960s and 1980s, however, in the 1990s growth took a downward trajectory. In the second half of the 1990s, it almost collapsed. The decade of 1990s was a lost decade in the economic history of Pakistan from the perspective of economic growth.

The low trend, with the exception of FYs 2003-2005, is continuing. During the period 2000-2021, Pakistan’s average annual real per capita GDP growth was 2.1%, the lowest among all the South Asian countries except Afghanistan (Table 1).

Low Savings and Investment

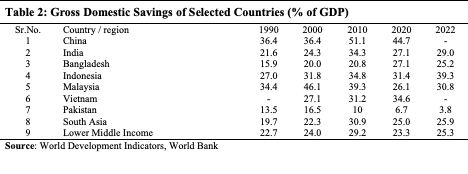

What is stopping Pakistan from riding the high trajectory of sustainable economic growth. Let us start with savings. Pakistan is a bad saver. Compared to its regional and other comparators like China, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, etc., Pakistan’s rate of saving is low. In 1990, its domestic savings were 13.5 % of the GDP, the lowest among the selected countries which gradually declined, except in early 2000s, when national savings increased around the level of 1990 due to improved macroeconomic environment and substantial increase in foreign remittances. Since 2005-06, Pakistan’s savings have persistently declined. In 2005-06, domestic savings were 13.4% of the GDP, which almost halved by 2013-14 when the domestic savings were estimated 7.54 % of the GDP (as per the Economic Survey of Pakistan 2013-14). Gross domestic savings of Pakistan were 3.8 % of GDP in 2022 whereas in case of China, India, and Bangladesh, domestic savings respectively are 44.7 % (year 2020 figure), 29% and 25.2 % (Table 2).

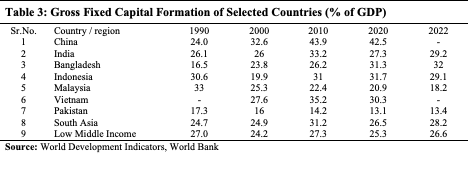

Low savings mean less investment or low capital formation. Gross fixed capital formation in terms of GDP or, in simple words, the investment ratio is persistently low, compared to regional and other comparator countries. Pakistan ploughs back less than half for capital formation compared to China, India, Bangladesh and other comparator countries (Table 3).

What are the main factors responsible for low savings and investment in Pakistan? Low tax revenue is perhaps the major culprit. Pakistan’s total revenue collection averaged to 12.8 % of GDP in the last decade, substantially lower than the South Asian average of 19.6 %. The worrying part is that total revenue collection in terms of GDP is on a decline. For example, total revenue collection averaged 13.2 % for the FYs 2013-17 and 12.5% for the FYs 2018-22. During FY 2021-22, Pakistan collected 12.4 % of GDP in total while tax revenues constituted 11.2 %. The revenues are persistently low and fall short of expenditures, resulting in large fiscal deficits. Tax exemptions, concessions, corruption in the tax machinery, political economy considerations, low fiscal capacity, and hesitation by the government to take hard choices are some of the reasons why Pakistan is unable to realize the huge tax potential. Large fiscal deficits contribute to the recurrent surges in the current account deficit. An analysis conducted by the World Bank shows that Pakistan’s fiscal deficit and current account deficit empirically tend to move together, meaning thereby that a strong correlation exists between the two. The financing of fiscal deficits generates other related but distinct macroeconomic challenges.

Large fiscal deficits have led to accumulation of huge public and publicly guaranteed debt, which stood at approximately 78 % of the GDP at the end of FY 22. Moreover, extensive borrowing from the financial sector crowds out the private sector from the credit market. Large public debts also crowds out development expenditure, having negative externalities for long-term growth. Debt servicing costs constitute a big share of the fiscal expenditures, which have now increased to an unsustainable level. During FY 22, interest payments stood around 4.7% of GDP and accounted for 35 % of the total federal expenditure. Large expenditure on interest payments and other pre-committed and largely rigid expenditure like government salaries, pensions, and government operating expenditures leave little for growth-enhancing expenditure and public investments. Subsidies to state owned enterprises (SOEs), security, contingency expenditures, and salaries to the public sector crowd out public sector investment.

In order to fill the savings-investment gap, Pakistan has to rely on foreign inflows. Foreign inflows have an in-built element of volatility. Pressure on reserves creates unsustainable current account deficits and macroeconomic instability. A nexus between the sovereign and commercial sector is apparent. The share of foreign debt and debt service payments is rising since 2014 which has increased the level of currency risk. The issue with the foreign bilateral and commercial loans is that they were primarily mobilized to support foreign currency reserves. External debt of Pakistan accounted for 32.1% of the total stock of federal debt outstanding on 30th June 2022 with 10% of total debt service payments. It means that Pakistan’s public debt problem is not basically an external debt problem, rather it is largely a domestic debt problem.

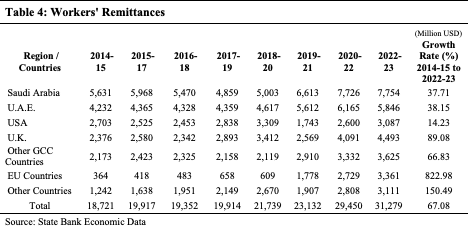

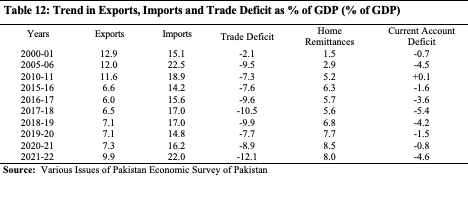

Foreign exchange reserves and the exchange rate are under constant pressure due to liberal capital account regulations, increasing payments for imports, and stagnant exports. The external debt to export ratio was 314.3 % in FY 2018 which in FY 2022 was 305.4 %. An analysis of Pakistan’s current account balance since FY 2000 shows that it has remained in the negative, except for FYs 2004-05 and 2005-6. The current account deficit in FY 2018 was 4.2 % of GDP which increased to 4.6% in FY 2021-22 but narrowed down in FY 2022 and 2023 due to the import compression policy of the government. The real interest rates in Pakistan have mostly remained in the negative. For the FY 2022, it was – 3.9 % of GDP. A decrease in real interest rate lowers the opportunity cost of capital and therefore increases desired capital stock and investment spending. Foreign remittances, despite all odds, have shown steady growth (Table 4) which could have be even higher had financial and political stability prevailed in the country. Due to consistent devaluation and prevalent instability (financial as well political), it is quite likely that large amounts of remittances were not sent to Pakistan through official banking channels.

Low Financial Inclusion

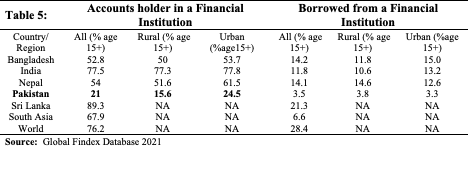

Financial inclusion and availability of credit are highly significant for promoting entrepreneurship. Besides crowding out credit for the private sector, other factors hindering the availability of finance for investors and entrepreneurs are also at play. Weak financial intermediation, high collateral requirements, and financial illiteracy are some big hindrances in the availability of finance in Pakistan, especially to small and medium enterprises. Jim Kim, a former World Bank President, wrote in a blog on financial inclusion for poverty reduction, “People who are unbanked struggle to save, plan for the future, start a business, or recover from unexpected losses. Small businesses without access to affordable financial services or credit cannot acquire capital to invest, grow, and create jobs. Financial access provides the building blocks people and businesses need to manage their economic well-being, and promote savings, investment, job-creation, and growth. Financial access also empowers women by making it easier for them to build wealth and create small businesses.”2 Pakistan lags behind in financial inclusion indicators in comparison to other South Asian countries. In Pakistan only 21% (of 15+age) hold accounts in financial institutions. In Sri Lanka, India, and Bangladesh, 89.3%, 77.5% and 52.8% respectively hold accounts in formal banking institutions (Table 5).

Pakistan embarked on structural reforms during the 1990s in the banking sector with a view to make the banking sector more efficient. These reforms reduced the footprint of the public sector in banking, but in terms of access the banking sector leaves much to be desired. Most of the population, especially in the rural areas, still does not have access to banking services. High interest rates coupled with high intermediation costs are still big concerns. Lending rates are comparatively high due to preference of the commercial banks to hold public securities. Deposit rates are low as deposits are held in banks for transactional purposes and banks as such do not attract savings of the people.

Pakistan’s monetary policy is operating in an environment where fiscal deficits and government debts are increasing and the government is continuously borrowing from the central bank3. Lending-deposit interest spread is a good measure of financial efficiency. Large interest rate spreads in Pakistan, among other factors, are driven by the opportunities for the banks to earn income from non-core business activities4. Domestic financial constraints in Pakistan are also driven by lack of financial depth. An average Pakistani household is still outside the formal financial system and does not use the banking system for depositing their savings. Over half of the population saves but not all entrust their money to formal financial institutions. One-third of the population borrows but only 3.5% use formal financial institutions. About half the population uses informal sources of credit where the interest rate charged, in most cases, is exorbitantly high.

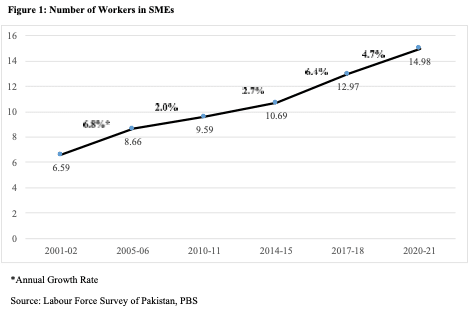

SMEs are considered growth engines of the economy as they create jobs, foster entrepreneurship, and provide depth to the industrial base of the economy. But SMEs get a disproportionately small share of credit relative to their contribution to the overall economy of the country. According to some estimates, there are around three million SMEs in Pakistan that, according to the Labour Force Survey 2020-21, employ 14.9 million labour force. Yet, SMEs get only 6% share of private credit despite providing over 35% non-agricultural employment in the country. The contribution of SMEs to employment as well as GDP has persistently increased, despite limited access to credit, etc., reflecting on their potential for economic growth and employment generation.

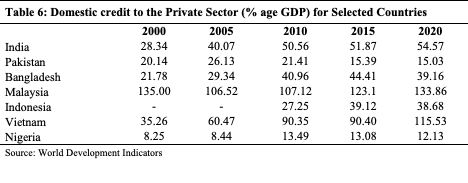

The credit extended by banks to the government rose by more than 400% in decade 2011-2021. The increased exposure to the public sector crowded out credit for the private sector. The credit to the private sector, in terms of percentage of GDP, has decreased over time. In 2020 it was just 15.03%, the lowest in emerging markets. (Table 6).

According to a study5, economic and cultural factors like poverty, financial illiteracy, and religious beliefs also hinder access to finance. Resultantly, most individuals and small firms use informal sources of borrowing rather than having to resort to financial institutions. Weak financial intermediation, low financial inclusion, and reduction in credit to the private sector are big constraints. Foreign remittances have traditionally remained an important source of finance, but the exogenous sources of foreign funds have not translated into productive investment. Generally, such flows ended up in real estate which resulted in a surge in real estate prices causing bubbles in the economy.

Low Foreign Direct Investment

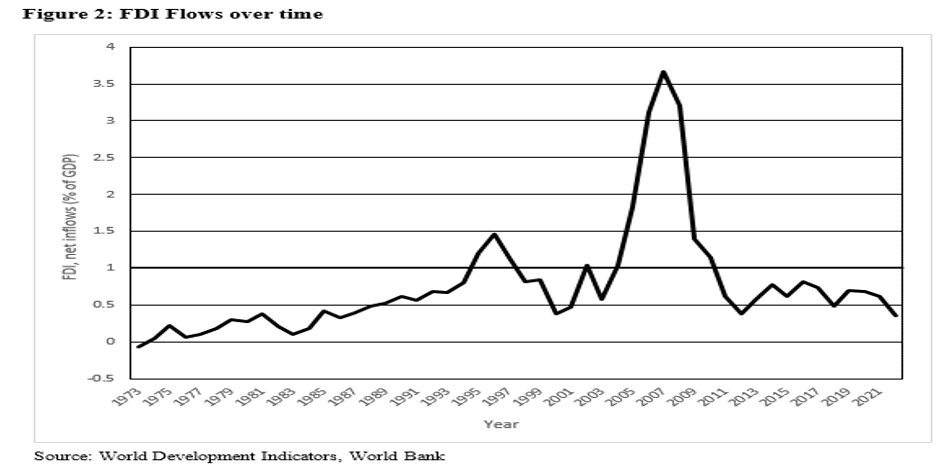

Traditionally, Pakistan has remained a poor attraction for foreign investment. According to World Bank data, FDI inflows into Pakistan remained less than 1% of the GDP since 1973, with the exception of the period 1995-1997 and 2004 to 2010. For the years 2006, 2007, and 2008, Pakistan attracted substantial amount of FDI (above 3% of GDP). Since 2011, a downward trend started which has persisted (Figure 2).

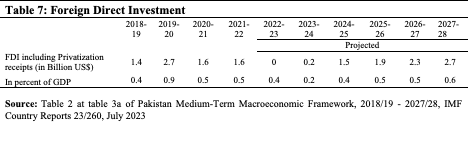

“The reduction in external inflows has aggravated internal and external financing issues. Pakistan has increasingly relied on monetary and central bank financing of the current account and fiscal deficits. The diversion of commercial financing to government bonds issued to finance the fiscal deficit has reduced credit for the private sector”6. The problem of low FDI is connected to bigger issues of uncertainty and instability. It is hard for the investors to invest in an environment which lacks policy uncertainty. If the rules of the game change frequently, nobody would take the risk of investment. The Public Investment Policy 2023 rightly emphasizes on reducing the cost of doing business, streamlining business processes, creation of clusters and special economic zones, and ensuring greater convergence between trade, industrial, and monetary policies. The said pillars of the Investment Policy cannot deliver unless the factors of uncertainty and political instability are addressed. Concrete measures are required, both at the micro level and macro level, to improve the investment climate. According to World Bank projections, the chances of some dramatic increase in FDI do not seem propitious in the near future (Table 7).

Public Infrastructure

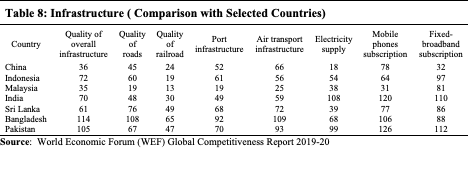

Poor quality of infrastructure is another big chain that binds the economic growth of Pakistan. According to the Global Competitiveness Report 2019-20 (latest available), Pakistan was ranked 110 out of a total 141 countries which is not an enviable position. An analysis of various categories of infrastructure shows that in terms of quality of roads, Pakistan sits at 67. With regard to Port infrastructure, Pakistan’s ranking is 70. Pakistan fares low compared to India, China, Malaysia, and Indonesia in terms of various variables of infrastructure such as the quality of roads and railroads, air transport structure, supply of electricity, etc. (Table 8).

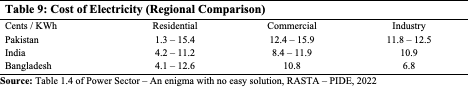

According to the World Bank7 “Pakistan’s public infrastructure has improved over the last 50 years, but slowly, resulting in many gaps that place the country at a disadvantage to competitor countries”. The power sector of Pakistan in particular merits mention due to its overall significance for industrial development and economic growth. This sector faces numerous challenges like expensive fuel mix, unreliable supply, and high circular debt. More than 40% of electricity generation is from imported fuels. An increase in international prices or devaluation of the Pakistani rupee increases the cost of electricity generation and often results in load shedding and an increase in the amount of circular debt. Transmission and distribution losses are high and theft of electricity is widespread. The circular debt (CD) i.e. the power sector deficit which originated in 2006 has become a big economic woe for Pakistan. At the end of June 2022, CD was estimated at around Rs. 2.25 trillion or 3.4 % of the GDP. The government borrows from commercial banks to finance the power sector and thus reduces availability of credit to the private sector. The cost of electricity is comparatively high for all categories of consumers in comparison to the region (Table 9), having adverse implications for the competitiveness of businesses and economic growth.

Low Human Capital

Besides hard infrastructure like roads, ports, etc., Pakistan lags far behind on soft infrastructure that is quality education and skills. It is bracketed with the countries having poor human development indicators. According to Global Human Development Report 2022, Pakistan’s HDI rank is 161 out of 192 countries. It is 142 out of 146, i.e. among the bottom five as per WEF’s Global Gender Gap Report, 2023. Pakistan has certainly made some gains but the situation is not enviable as almost half of the women in the age group of 15-25 are uneducated. Its education system is ranked among the least effective. One in ten of the world’s primary-age children who are out of school live in Pakistan. This makes the country second in the global ranking of out-of-school children, after Nigeria. It is the lowest in the Human Capital Index (HCI) in South Asia (ranks with Afghanistan). It may be appreciated that on average HCI and per capita income are correlated.

According to ASER, 46% of boys aged 5 to 16 and 38% of girls of the same age bracket could read sentences in Urdu or a regional language. Similarly, only 48% of boys and 39% of girls could read some English words. Regarding numeracy skills, 43% of boys and 36% of girls could subtract. Moreover, 75% of the students cannot read and understand a simple text by age 10.8 Internationally, Pakistani students’ achievement in mathematics and science is the second lowest, after the Philippines. In Mathematics and science the average score of 4th grade Pakistani students was respectively 329 and 290, almost half of that of Singapore, the top scorer9. The World Development Report, 2018 correctly calls such learning outcome gaps or education poverty “hidden exclusion”.

An analysis of the World Bank’s HLO database shows that countries like Congo, Central African Republic, Chad, Liberia, Nigeria, Rwanda, etc., which score less than Pakistan on HCI belong to the African region. Only two countries, Afghanistan and Yemen, lie outside the African region which have a lower HCI (respectively 0.4 and 0.37) compared to Pakistan. Countries like Gambia, Namibia, Myanmar, Cambodia, Haiti, and Nicaragua fare better than Pakistan on the said score. Similar is the case with health indicators. Child undernutrition is a case in point. Pakistan falls among the worst countries in terms of low birth weight, stunting, wasting, and underweight children—some important variables determining the nutritional status of children. The economic losses from undernutrition are estimated to be approximately US$ 7.6 billion annually, corresponding to nearly 3% of GDP.10 According to the Pakistan National Nutrition Survey (PNNS), the prevalence of low birth weight is estimated to be 20.1%.

In addition, women are hugely underrepresented in the labor force in Pakistan. ILO estimates show that female labour force participation (FLFP) in Pakistan is far below the Sub-Saharan African region, China, Vietnam, South Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. The ratio of male to female participation in the labor force is 30.4 as per 2021 estimates of ILO. The said ratio in the case of Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Indonesia is respectively 46.29, 47.37, 66.68 and 65.30. For India, it is 31.62. According to the World Bank11 “several cultural factors shape the speed of human capital gains in Pakistan. At more than 50% idleness—not in school or training, not employed, and not looking for work—among Pakistani women is the highest in the world. Women with a higher education are less likely to enter the labor force than women with no education, except for women in urban areas with a pre-university and above education. Marriage is associated positively with labor force participation for men and negatively for women”.

Low level of human capital or inadequate skills hinder firms from operating at Production Possibility Frontiers (PPF) (thus forcing the firms to be less efficient). Furthermore, the firms are required to bid up for scarce skills which renders their returns less competitive compared to other potential locations. On the other hand, the problem of costs or risks associated with hiring needed skills is the problem of appropriability as the firms’ ability to privately appropriate the returns to their investment is low due to microeconomic risks like labor market rigidities (like binding minimum wages or employment regulations) which reduce the firms’ prospects to earn a reasonable return on their investment. Education and skill levels of the workforce are undoubtedly low and we may safely hypothesize that a low supply of human capital is a constraint on economic growth.

The problem is, however, on the demand side as well. Had the problem been just on the supply side, then the logical corollary would have been higher returns on education. And the labour market would have been signaling to pay more to the educated few but this is not the case. Rather, educated youth are migrating to other countries to seek jobs. In the last two decades, migration of highly qualified people has increased massively due to a lack of absorption capacity of the labour market (Figure 3). The returns on education for various levels of education show that higher earnings are associated with higher education and professional degrees.

However, overall returns on education for university degree holders is low12. Unemployment among engineering, computer, and other graduates has increased in the last few years. For example, the unemployment rate among engineers increased from 11% in 2018-19 to 23.5% in 2020-21. A similar situation prevails with graduates in other disciplines like medicine, computer, and agriculture.13

The low quality of education and brain drain have implications for productivity which is invariably low across all the sectors of the economy as evident from the share of productivity in economic growth. An analysis14 by PIDE for the period 1972-2019 suggests that the average growth rate of Pakistan for this period was 4.81% per annum. Labour, capital, and TFP respectively showed annual average growth rates of 2.21%, 4.11% and 1.62% with an average investment ratio of 18%. The low productivity is partly due to the misallocation of resources. According to a World Bank report,15 “low level of innovation exchange in Pakistan is long-standing structural constraint to its growth. Innovation promotes productivity, job creation and knowledge sharing. Innovation exchange is directly related with Pakistan’s performance in export sophistication and productive diversification. Pakistan is ranked lowest on three global innovation indexes—global innovation, global competitiveness, and innovation capacity”.

Taxation Structure

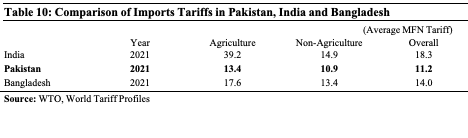

High tax rates can be another factor affecting private sector productivity, as entrepreneurs hesitate to invest when major chunks of their profits are extracted by the state through taxation. However, interestingly Pakistan has the lowest tax rate among its comparators in the region, like India and Bangladesh. It can be argued that factors other than tax rates such as cumbersome tax procedures and complexity of tax codes also discourage growth of businesses. The huge informal sector in Pakistan and businesses preferring to remain in this sector leads to speculations that the taxation structure of Pakistan is complex. This argument is valid to some extent. Pakistan, however, instituted numerous reforms to simplify and modernize its tax and trade regime. These reforms have shown some success. For example, customs procedures have been simplified and tariffs rationalized. The customs clearance time has decreased. Over 50% of imports and 95% of exports are cleared under the green channel of the WeBOC system of Pakistan Customs without any physical interaction with customs inspectors. Moreover, Pakistan embarked on a liberalization programme in the 1990s and gradually made drastic reductions in tariff rates. In 2000, an average MFN rate was around 25% which in now around 11%, a reduction of over 100% in two decades. The average MFN tariff for Bangladesh and India is respectively 14% and 18% (see Table 10). India has kept very high tariffs to protect its domestic agriculture sector, whereas Pakistan, with regards to its agricultural products, is quite liberal. Cotton is a case in point which is importable into Pakistan at zero customs duty.

Despite huge reductions, the fact remains that the tariff slab of 20% still practically covers the highest number of tariff lines. The tariff slab of 20% or higher is generally applicable to the goods which are manufactured locally. In addition to customs duty, additional customs duty (ACD) and Regulatory duty (RD) are also charged at the import stage against a substantial number of imported items. Pakistan has developed a system, over the years, of collection of direct taxes in the mode of indirect taxes. Withholding tax (WHT) and Sales tax are collected at the import stage with certain exemptions and concessions in statutory rates. Some statistics and trends of tax collection can clarify the pitfalls of the tax structure in Pakistan. (1) Around 50% of tax revenue is collected by the Federal Government at the import stage in the form of Customs duty, sales tax, Federal Excise duty (in sales tax mode) and withholding tax. (2) Sales tax is collected against imports as well as domestic supplies. On average, the collection of sales tax on imports is higher than the collection from domestic supplies. (3) Income tax is collected under three major heads: withholding tax, voluntary payments, and tax out of demand. Around 65% is collected as withholding, 28% as voluntary payments, and just 7% out of demand. (4) An analysis of tax collection for the period 1990-2020 shows that out of demand payments have decreased in percentage terms (in 1990-2000, 14% collected out of demand which was reduced to 7% in 2010-2020). Voluntary payments were 34% in 2000-2010 which were reduced to 28% in 2010-2020. (5) Withholding tax continues to be the major mode of collection of income tax.

Withholding tax in Pakistan as a source of revenue is “too large in scale, size, scope, and intensity” and is negatively impacting the entire economic system as withholding taxes “get stuck into the pricing structure of the final goods and services produced in the country rendering them price-incompetitive in the international market”16. High incidence of taxes at the import stage creates an anti-export bias and makes exports less competitive and creates incentives for smuggling and misinvoicing. The tax structure of Pakistan is also beset with several other distortions, anomalies and imbalances. For instance, contributions of agriculture, industry, and services sectors to GDP are 23%, 19%, and 58% whereas their respective contribution to revenue is 2%, 53%, and 45%.

Weak Institutional Quality

Security of property rights is considered vital for economic growth. Economists have emphasized four main channels17 through which property rights affect economic activity. First, expropriation risk—insecure property rights imply that individuals would fail to realize the fruits of their investment and labour. Second, insecure property rights lead to costs (unproductive expenditure) which the individuals have to bear to defend their property. Third, failure to capitalize on gains from trade and exchange, meaning a productive economy requires that assets be utilized by those who can do so more productively and improvements in property rights facilitates this. Fourth, property supports other transactions. Modern market economies rely on collateral to support a variety of financial market transactions. Secure property rights increase productivity by enhancing such possibilities. De Soto18 has postulated that capitalism triumphed in the West through formal property rights. People in the developing countries accumulate substantial amount of assets, however, these assets remain dead capital, as they cannot convert their assets to productive capital for want of formal titling and weak enforcement of property rights.

Enforcing property rights and contracts depends upon the institutional quality, especially of the courts. The capacity of the courts to decide cases promptly determines the enforceability of property rights and contracts. The way our judicial system operates hardly helps enforcement of property rights and rule of law. It limits access to justice leading to disaffection among the people. Courts are understaffed and judges inadequately trained. Infrastructure is poor. A lack of training of the judges and alleged corruption among some of them creates endless delays in the settlement of cases. The Government announced a National Judicial Policy in 2009 with a plan to redress the flaws. A weak judicial system has created distrust, anger, and frustration among the people. According to a report, “the lack of justice and public frustration over the existing legal system in Swat Valley contributed to an increase in support for the extremist brand of brutal but decisive law.”19

According to Doing Business 2019, Pakistan ranks at 156 against the indicator of enforcement of contracts and on average, it takes 1071.2 days to resolve the dispute of contract. The cost involved on average is 20.5% the value of the claim. Simply, disputes of property drag on for years. Titling of land is a complex issue in Pakistan and a lack of clear titles is a big hindrance to the realization of the potential of the land. Access, speed, and quality of the judiciary are not only essential for increasing deterrence to reduce future litigation but also for the development of a modern economy. A firm-level analysis shows that judicial efficiency and firm productivity are positively connected and judicial reforms targeting all above characteristics (access, speed, and quality) increase firm productivity20. The situation of contract enforcement in Pakistan is very poor, having serious negative implications for economic growth. A study of the lower courts finds that an average shelf life of a civil case in the province of Punjab is over three years and, on average, a case requires 58 hearings from its institution in the civil court to the passing of a decree.21 The disputes of titles are many and hardly 10-20% of land can be used as collateral with financial institutions due to joint ownership or ambiguity in titles. The only evidence of title in Pakistan is the registry system which can be challenged on the basis of oral transactions and earnest money. The laws of preemption and rent further complicate land-related transactions and generate disputes.

According to an estimation, 60-70 % civil litigation in Pakistan is land-related. Land-related civil litigation turns into criminal litigation in 40-50% of the cases22. Empirics suggest that speedy disposal of civil cases positively impact the firms’ contracting behaviour and economic performance. A decrease in breach of contracts creates more investment and provides better access to finance23. Judicial efficiency also impacts entrepreneurship. Slow dispensation of justice reduces incentives to start businesses and thus reduces economic growth24. “The theories that lay emphasis on encouraging savings to increase growth, assume that savings are converted into investment. The poor implementation of collateral laws and weaker land titles constrain bank lending and therefore investment activity. Therefore the increase in savings per se will not increase investment because legal institutions that are supposed to facilitate the investor are not strong enough”25.

Empirics suggest that good governance is associated with higher growth rates. An ADB study26 using the World Bank’s worldwide indicators of governance (government effectiveness, political stability, control of corruption, regulatory quality, voice and accountability, and rule of law) has suggested that developing Asian countries with a surplus in government effectiveness, regulatory quality and corruption control are observed to have grown faster than those with deficit in these indicators. Pakistan has consistently fared low against World Bank governance indicators.

Pakistan is bracketed with countries like Nigeria and Kenya in the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) of Transparency International. With regard to human development, Pakistan remains low in its ranking, as measured annually by Human Development Index (HDI). Similarly, other reports like Doing Business of the World Bank (published till 2020) and WEF’s Global Competitiveness Index bracket Pakistan with countries earning very low scores. According to the World Economic Forum’s report, each year corruption, inefficient government bureaucracy, government instability, policy instability, and crime and theft appear among the top problematic factors for doing business in Pakistan. The said factors are directly linked to bad governance and poor institutional quality. The results of Investment Climate surveys rate corruption as one of the major obstacles faced by businesses. Pakistan Planning Commission’s Framework for Economic Growth identifies microeconomic factors related to bad economic governance as the binding constraint for growth27.

According to one of the World Bank’s report28 “poor governance is a binding constraint to economic growth in Pakistan, with strong distributional and security-related implications. Pakistan ranks among the weakest performing countries on governance indicators worldwide”. Corruption, poor law and order situation, weak rule of law, and political instability are all manifestations of poor governance and poor institutional quality. “State has low capacity to enforce the law. Political discourse prefers passion to reason and does little to clarify issues for the citizens. Even on one issue as clear-cut as terrorism, there is no unanimity of view and a fair bit of fudging by some political parties and the media. A clear lack of national purpose along with the level of violence that exists in society precludes the country’s growth in any sector, societal or economic. The result is that Pakistan is a weak state with limited ability to tax, regulate, and protect citizens.”29 Low growth and poverty are rooted to a great extent in institutional decay as well.30 The WEF global competitiveness reports listed each year the most problematic factors for doing business for each country separately till 2018 when it discontinued such identification of factors in categorical terms. An analysis of the reports for the years 2008-09 to 2017-18 identifies corruption, inefficient government bureaucracy, policy instability, government instability, inadequate supply of infrastructure, and crime and theft as the top most factors every year with slight variations of rank. These factors are basically symptomatic of bad governance. The implication is that corruption and poor governance are the binding constraints for economic growth in Pakistan.

Macroeconomic Instability

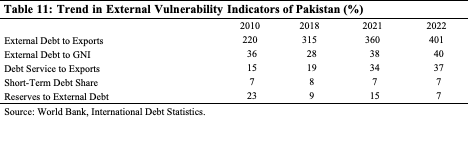

Pakistan seemed to be on the verge of a financial crisis as Pakistan could have faced a situation of default. Foreign exchange reserves stood just at US $ 5.5 billion at the end of December 2022. It faced a situation of external vulnerability. Overall, Pakistan maintained 3 months import cover which diminished to just one month cover due to the increase in import prices. To handle this situation, Pakistan had to adopt a policy of import compression, through use of tariff and non-tariff barriers (like delayed issuance of financial instruments by the banks) as the magnitudes of the external vulnerability indicators increased. The level of external debt to GNI increased from 36 % in 2010 to 40 % in 2022. The most severe deterioration happened in the indicators linked to exports due to limited growth in exports. The level of external debt to exports increased to over 400% and the debt servicing to exports went up from 15% in 2010 to 37% in 2022 (See Table 11).

Exchange rate volatility that started around May 2021, continued unabated adding uncertainty and inflation. It took almost one decade to double the dollar from Rs.75 to 150 but in less than 30 months, its value doubled against the rupee. The big gap between inter-bank exchange rate and the open market rate (which rose to the range of 15 to 20%) further complicated the situation by encouraging diversion of remittances and exports through unofficial channels. The large gap between demand and supply of dollars created a black market premium and the scarcity of foreign exchange problem complicated further. Generally, firms would prefer to go to the official market i.e. banks and authorized money exchangers for foreign exchange as informal channels entail additional transaction costs. So, the increase in black market premium itself is indicative of a shortage of foreign exchange. The challenge of external borrowing is also connected to the scarcity of foreign exchange reserves as foreign lenders are shy to lend due to debt sustainability concerns. The State Bank of Pakistan started a type of rationing of dollars to the business firms to mitigate the problem of the balance of payments. Shipments of importers were stranded at clearance ports and costs further increased due to demurrage charges etc., further reducing competitiveness of the businesses.

The depletion of foreign reserves aggravated the microeconomic challenges for individuals and households in the form of high inflation rate. It was 3.9% in 2017-18, rose to 12.2% in 2021-22 and touched the peak of 25.2% in the first half of 2022-23. Due to the devaluation of the Pakistani rupee, imports became expensive and contributed to inflation through the exchange rate pass-through effect. “Too much money chasing too few goods”, apparently should not have been the case in Pakistan because of high interest rates, however, in actuality this explanation squarely applied to the inflation situation in Pakistan. The monetary policy of Pakistan is a case of fiscal dominance due to huge borrowing by the government. The estimates31 suggest that inflationary expectations, rise in import prices, and devaluation of rupee respectively contributed 42.5%, 19.3% and 19% to the rate of inflation during the period 2019-20 to 2022-23. Food prices are an important part of the inflation story. Floods, due to climatic change, induced shocks to the supply and production of food. And unfortunately, food prices increased much more than the overall rate of inflation, thus severely hitting the vulnerable and poor people in the country.

The macroeconomic problem of Pakistan has basically got fiscal roots.

Stagnant Exports

Exports are an important stimulator of economic growth and development. They not only bring dollars but also make the exporting firms more productive. Export diversification not only leads to higher growth but also helps overcome export instability or the negative shocks of the terms of trade. Trade diversification promotes economic growth through structural transformation. Export-led growth was an important development strategy for the countries known as the Asian Tigers. South Korea, Singapore, and Hong Kong adopted export-led growth policies and achieved the status of developed nations. They achieved sustainable economic growth by integrating themselves into the global economy. Malaysia and Thailand also started the journey of export-led growth in the 1970s and substantially diversified their exports. The two countries decreased their export concentration in the last four to five decades. They moved into manufacturing exports like clothing and electronics and also developed resourced-based sectors. For example, Malaysia capitalized on its comparative advantage in palm oil and rubber while Thailand developed its agriculture and fish sectors into value-added products. China and Vietnam are two other pertinent examples whose high economic growth owes much to export diversification and structural transformation. Chile and Costa Rica in Latin America, and Tunisia and Botswana in Africa are developing countries that have made exports an engine of growth for their economies. Most of these economies transitioned from exports of primary products to value added and high- tech exports.32 Pakistan has witnessed a continuous decline in exports in terms of percentage of GDP. In 2000-01, exports constituted around 13% of GDP which virtually declined every year and hovered in the range of 6 to 7% between 2015-16 to 2020-21 with around a two point increase in 2021-22 (Table 12).

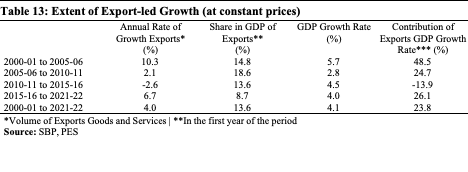

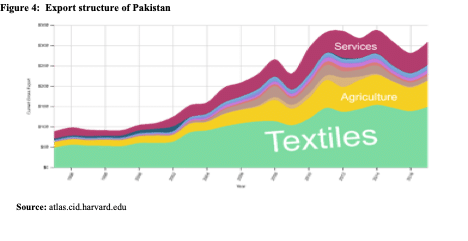

Pakistan’s exports are concentrated in low complexity items like textile and agriculture. An analysis of its export mix shows that a majority of its exports belong to low complexity items like textile, cotton, apparel, clothing, cereals, leather, minerals, fish, fruit, nuts, plastics, etc. The share of high-tech exports hovers around 2%. On the contrary, high-tech exports of India, Vietnam, and Malaysia respectively hover around 10%, 40 % and 50%. Product diversification in exports is low. Pakistani exports are highly dependent on textiles with a share of over 55% in the total exports. The index of export diversification, the value of which ranges between 0 and 1, has shown minor improvement from 0.535 in 2005-06 to 0.581 in 2021-22. This phenomenon raises concerns regarding export dynamism33. Pakistan’s share in high-tech contents (which hovers around 2%) has not changed since the 1980s. In terms of destination, Pakistan’s exports have not witnessed any tangible improvement in diversification in the last decade or so. Pakistan, since its very inception, followed an import substitution policy which was slightly reversed with the tariff liberalization policy in the 1990s. The exports witnessed around 48 % growth in the period 2000-01 to 2005-06. Thereafter, growth rate of exports had declined sharply. (Table 13).

Product diversification and export dynamism are lacking due to low productivity and innovation. Exports are stagnant affecting the current account deficit and other macroeconomic variables. Structural transformation is slow. According to the Labour Force Survey, 37. 45% of the people, 10 years age and above, are employed in agriculture compared to 14.9% in manufacturing. The contribution of agriculture to GDP has declined, yet this sector remains the biggest employer and the manufacturing and services sectors have failed to provide jobs proportionate to their contribution to GDP. The structural transformation of the economy is closely linked to economic development. During the process of structural transformation, the economy transitions from the production of low-value primary products to high-value, and high-tech sophisticated products, and the workers move from low-productivity to high-productivity sectors. As a result, national income increases and workers are better off due to an increase in their productivity and wages. The contribution of the services sector has increased substantially but without a commensurate increase in employment. The manufacturing sector is stagnant, both in terms of its contribution to GDP and employment since 1970.

Research from Growth Lab of Harvard34 suggests that generally countries whose exports are more complex than expected for their income level comparatively grow faster. A mix of a country’s products is a predictor of not only the subsequent pattern of diversification and economic growth but also a good predictor of economic inequality as the ability of an economy to generate and distribute income has strong correlation with the mix of products a country is able to produce and export.35 Hausmann et al have developed an indicator EXPY which measures productivity level associated with the export basket of a country and their findings are that countries which produce high-productivity goods grow faster compared to countries producing low-productivity goods. Simply countries are what they export.36

Constraints hindering Pakistan from producing high-tech, high-value goods are basically two-fold. First, Pakistan has specialized in sectors like textile and leather. The skill set acquired for producing these products is hardly relevant for the production of high-tech capital-intensive and consumer durables. Second, public policies such as the industrial policy, technology policy, innovation policy, etc. have not been effectively utilized to facilitate the jump from the periphery to the core of the product space. Low competitiveness and low value-added exports have become big constraints for the economic growth of Pakistan.

Conclusion

Both the public and private sectors have got vital roles in enhancing productivity and stimulating economic growth. The responsibility of the creation of an enabling environment for businesses to grow, by enhancing access to quality public goods and services rests with the government. The private sector requires to make itself competitive in the changing world, not through shielding behind state protections, but by making efficient use of inputs like capital, labour, water and energy. So rebalancing of the roles of the private and public sectors would be required. “Entrepreneurship is effectively the willingness and capacity of individuals to take risk in the creation of a business opportunity. This requires an ecosystem that encourages entrepreneurship and innovation through ‘institutional technology’ whereby the institutions, policies, business culture and rule of law provide market dynamics that provide a level playing field”37. Human resource development, overhauling the taxation structure, speedy contract enforcement, and development of a vibrant export sector should be some of the priority areas of any reform agenda for the creation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Notes and References

1 Pilling, David ‘The Growth Delusion: Wealth, Poverty, and the Well-being of Nations’, 2018. This book provides an incisive critique of economic growth and GDP in an entertaining and journalistic style.

2 End extreme poverty? Let’s start with financial access for all (blog February,2015)

3 Ehsan U. Choudri and Hamza Malik, “Monetary Policy in Pakistan: confronting fiscal dominance and imperfect credibility”. International Growth Center (Dec2012)

4 Mahmood ul Hassan Khan & Bilal Khan, “What drives interest rate spreads of commercial banks in Pakistan? Empirical evidence based on panel data”, SBP Research Bulletin, 2010

5 Tatiana Nenova, Cecil Thioro Niang & Anjum Ahmad, “Bringing finance to Pakistan’s poor: A study on access to finance for the undeserved and small enterprises”, World Bank (May,2009)

6 Jose Lopez-Calix & Irum Touqeer, “Revisiting the constraints to Pakistan’s growth”, Policy Paper series on Pakistan, The World Bank ( June, 2013)

7 Pakistan—Finding the path to job –enhancing growth, The World Bank, 2013

8 ASER, 2019.

9 TIMMS,20119

10 ‘The Economic Consequences of Undernutrition in Pakistan: An Assessment of Losses’, a study conducted by the Ministry of Planning, Development, and Reforms of Pakistan in collaboration with WFP in 2017. This is available online on the official website of the Ministry.

11 The World Bank 2013 ibid

12 See PIDE knowledge Brief No.2023: 101, March,2023

13 See special report of PIDE “Why our Graduates are migrating”, 2022

14 PIDE (2020), “Total Factor Productivity and Economic Growth in Pakistan: A Five Decade Overview”, PIDE Working Paper No.2020: 11, Islamabad.

15 The world Bank 2013 ibid

16 Muhammad Ashfaq Ahmed (2020), “Pakistan: Witholdingisation of the Economic System- A Source of Revenue, Civil Strife, or Dutch Disease?” Pakistan Development Review, 59:3, Islamabad.

17 Tim Besley & Maitreesh Ghatak, “Reforming property rights”, VOX, CEPR’s Policy Portal (April 22,2009)

18 “The Mystery of Capital: Why capital triumphs in the West and fails everywhere else”, Basic Books Hardcover Edition (2000)

19 Pakistan 2020, A Vision for Building a Better Future, Asia Society Pakistan 2020 Study Group Report, p. 22.

20 Chemin, M (2020), ” Judicial Efficiency and Firm Productivity: Evidence from a world database of judicial reforms”, Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol.102, issue1, pages 49-64.

21 This study was conducted by Umar Gilani and Usher Qazi in 2011 and is available in the library of the Supreme Court. Another study conducted in 2016 under the auspices of the European Union’s Access to Justice program also came up with similar results of inordinate delay; Another report (of Legal Society) on the trial courts of Karachi, based on data for the period May 2013 to March, 2016, found that at any given date there was 58.65% chance that the case would be adjourned.

22 “Economic Analysis of Law in Pakistan”, PIDE Knowledge Brief No 6/2020.

23 Chemin, Matthieu (2010), “Does Court Speed Shape Economic Activity? Evidence form a Court Reform in India”, Journal of Law , Economics and Organization

24 Chemin, Matthieu (2008),” The Impact of the Judiciary on entrepreneurship: Evaluation of Pakistan’s “Access to Justice Programme”, Journal of Public Economics.

25 Abdul Qayyum et al 2008

26 Xuehui Han, Haider Khan & Juzhong Zhuang, “Do governance indicators explain development performance? A cross-country analysis”, ADB Economic Working Paper Series (2014)

27 Pakistan: Framework for economic growth, Planning Commission (May 2011)

28 The World Bank 2013 ibid

29 IPR ibid

30 Akmal Hussain, ‘Institutions, economic structure and poverty in Pakistan’, South Asian Economic Journal (2004)

31 Dr. Hafeez pasha

32 UNCTAD 2008 paper

33 A net creation or destruction of exported items is considered a proxy for export dynamism. A net positive creation i.e. number of creation minus the number of destruction of exported items, is indicative of export dynamism. In case of Pakistan, we do not see much increase in the number of exported items which are yet concentrated in few sectors.

34 See Atlas of Economic Complexity of Harvard ( atlas.cid.harvard.edu )

35 Hartmann, Dominick et al (2017), “Linking Economic Complexity, Institutions, and Income Inequality”, World Development, vol.93, pp. 75-93

36 Hausmann, Ricardo; Hwang, Jason & Dani Rodrik (2007), “What You Export Matters”, Journal of Economic Growth, Vol. 12, No.1.

37 New Growth Models: challenges and steps to achieving patterns of more equitable, inclusive and sustainable growth, World Economic Forum (January, 2014)

1 thought on “Economic Woes of Pakistan”

Pingback: Pakistan, Middle Powers and a Multipolar World - Criterion Quarterly Journal

Comments are closed.