Abstract

(The alarming escalation of violent extremism and terrorism in Pakistan, owing to instability in Afghanistan, not only catalysed grievous damage to Pakistan’s economy but has also led to widespread far-reaching human suffering due to indiscriminate attacks against innocent Pakistani civilians.

It is in South and Central Asia’s overall interest that Pakistan and Afghanistan resolve their seemingly intractable stalemate1. After all, both countries enjoy geographical and demographic contiguity and mutual economic interests. The dividends of peace would be immense. Afghanistan’s geo-strategic and geo-economic positioning at the very crossroads of South and Central Asia adds to its importance for Pakistan and vice versa. Pakistan, for its part, is trying its best to scramble for a peaceful and stable Afghanistan, yet the Afghan Taliban have made Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) an intractable issue and remain obstinately recalcitrant.

The Afghan Taliban’s non-co-operative attitude with regards to Pakistan’s legitimate demands (for sterner actions to be implemented against the TTP) hampers a full diplomatic entente cordiale between Islamabad and Kabul. – Author)

2023: A Blood-Drenched Year – Soaring Terrorist Attacks in Pakistan

A multitude of terrorist attacks of late have once again become a major concern for Pakistan. Pakistan reels under nefarious tactics of asymmetric shock and awe, instigated largely by the TTP.

Life-shattering TTP attacks have taken place, including a daringly criminal endeavour to seize control of a border district in northern Pakistan, as TTP miscreants attacked numerous villages in Kalash, Chitral—a top tourist destination bordering Eastern Afghanistan.2 Four soldiers and 12 terrorists perished. Pakistan’s government had to impose a three-day curfew. TTP chose Chitral due to its rugged mountainous terrain, mineral resources and it being well-suited to bolster their insurgent guerrilla warfare.

The bloodshed in Mastung3 in September 2023, serves as another grave indication of the ongoing escalation of terrorist militancy posing a severe menace to Pakistan’s security. In addition, a suicide attack targeting a Rabiyul Awwal (birth of the Holy Prophet PBUH) gathering in Balochistan resulted in 62 fatalities. On the same day, five more individuals fell victim to a deliberate assault in KP, further inflating the devastating death toll. This marked one of the deadliest days of 2023, with the greatest number of fatalities among security forces.

Terrorist assaults have become nearly a daily occurrence4, presenting a critical challenge for Pakistan, a country already entangled in manifold challenges. The sequence of killings throughout the country showcases the expanding capabilities of terrorist groups, engaged in increasingly bold and brazen blood-soaked atrocities.

It is not only the TTP but also groups like the Balochistan Liberation Army, Balochistan Liberation Front and others that have found safe havens in Afghanistan, especially in the Southern Afghan province(s) of Nimroz and nearby parts of Helmand, Kandahar, and Farah provinces.5

After Mastung’s murderous spree, Balochistan’s Information Minister, Jan Achakzai, warned of a ‘befitting retort” and accused India6 of playing a role in such a large-scale, highly co-ordinated, premeditated deadly massacre.7

Armed assailants continue their deadly offensives with impunity. The nature and extent of the violence indicate enhanced armament and meticulous organization among the militants.

An informative document from Islamabad’s Centre for Research and Security Studies (CRSS) highlights an overwhelming killing of more than 700 security forces and civilians in the first nine months of 2023. The report highlighted a dramatic increase in suicide bombings and insurgent raids, especially in southwestern Baluchistan and northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces. Some excerpts of the report are as follows:

“Pakistan’s security forces lost at least 386 personnel, 36% of all fatalities – including 137 army and 208 police personnel – in the first 9 months of 2023, marking an eight-year high as the country continues to battle proxy terrorism, largely in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. With 1087 violence-related fatalities recorded so far during the year, the outlaws suffered 368 (34%), followed by civilians with 333 (31%) fatalities…. Collectively, KP and Balochistan suffered a staggering 92% of all fatalities from January-September 2023.”

“As for the third quarter of 2023 (July-Sep) some 445 people lost their lives and 440 suffered injuries from as many as 190 terror attacks and counter-terror operations. KP and Balochistan provinces were the primary centers of violence, accounting for nearly 94% of all fatalities and 89% of attacks (including incidents of terrorism and security forces operations) recorded during this period.”

“July to September 2023 registered a staggering surge in violence by around 57%, while the total number of fatalities catapulted from 284 in the second quarter of 2023 to 445 in the third quarter (July-Sep) 2023. This encompasses an overwhelming 131% upward trend registered in Balochistan and 28% in KP. Punjab observed a significant 67% decrease in violence compared to Apr-June 2023, whereas Sindh witnessed a 283% rise in violence although the volume of fatalities was low.”

“Approximately 79% of all violence-related casualties recorded from July-Sep 2023 were from terrorism; with a 57 percent surge in nationwide militant violence over the last quarter. 141 terrorist attacks caused 318 fatalities and 381 injuries of civilians and security personnel. On the other hand, the security operations were as low as 49 leaving 127 outlaws dead and 59 injured. This worryingly shows a huge gap between the frequency of terror attacks and counter-terror operations as well as the number of outlaws eliminated in security operations.”

“Boring the heaviest brunt of violence, civilians were the biggest victims in this quarter; suffering nearly 58% of all casualties, followed by security personnel, suffering nearly 23%. The outlaws suffered the least; constituting only about 20% of all casualties in this period”.8

January-September 2023 showed worrisome tendencies related to security forces’ losses. First, “with 386 lives lost so far into the year, their fatalities have hit a record 8-year high, exceeding the 2016 level and highest since 2015.

Second, their percentage of the fatalities among other victims of violence recorded this year (nearly 36%) has also hit a record 11-year high.

Third, the period from 2021 onwards records a constant rise in their number of fatalities”.9

On 3 November 2023, three distinct attacks resulted in the tragic demise of seventeen Pakistani soldiers.10 In one of the attacks, militants struck a convoy in Gwadar, resulting in the loss of fourteen soldiers. Gwadar port possesses deep strategic and economic gravitas for Pakistan and is a jewel in the crown of the Chinese-driven CPEC Belt and Road project. Gwadar is at a cross-junction of international maritime and oil trade routes; despite delays and setbacks, it is poised to be a global trade hub for Pakistan.

Again, on 3 November, six civilians and a soldier lost their lives and twenty-four more were grievously injured from improvised explosive device (IED) blasts in Dera Ismail Khan. D.I. Khan is strategically significant for Pakistan, not just because it is one of Pakistan’s most resource-rich regions, endowed with oil and gas resources and is home to the D.I. Khan Economic Zone,11 accessibly located, it is also the second-most significant intersection of the CPEC route, on the Western Corridor.

Authorities have ramped up their kinetic efforts and commenced extremist clearance operations, especially in Balochistan and KP, in light of these lethal deadly attacks.

On 4 November, troops thwarted a militant assault on the highly sensitive Mianwali Training Air Base of the Pakistan Air Force, killing nine extremists. On 6 November, four troops, including a high-ranking officer, perished in an intelligence-based operation (IBO) in the strategic Tirah Valley of Khyber tribal district, which has played host to renegades and rebels since centuries.

The Tirah valley has historically been restive for Pakistan. Pakistan army mounted several kinetic operations in Tirah over the years, and in 2015 captured key passes in a remote region that was never before under total government control and was always a stronghold for the TTP and a hideout for TTP ally Lashkar-e-Islam (LI), and other extremists in nearby North Waziristan.12 It is the strategic Masatul pass, which links to Afghanistan’s restive Nangarhar province, through which TTP crosses into Pakistan and often return to their base.

Improved coordination among intelligence agencies, police, and Counter-Terrorism Departments (CTDs) has been pivotal, often underreported. Operations spanning from Gilgit to Gwadar, dismantling militant infrastructure, have thwarted terrorist attempts,13 safeguarding the populace in the recent wave.

Pakistan’s armed forces are our first line of defence. Most of the TTP terrorism is targeted at them (whereas others like ISKP aim at soft civilian targets). Though the TTP have a penchant for directing attacks at “hard targets” such as the military or LEAs, when they are given an opportunity, they also strike against civilian-centred “soft targets”,14 especially large public gatherings, in their major strongholds of KhyberPakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan. By doing so, these militants aspire to infiltrate urban areas by enfeebling urban defences.

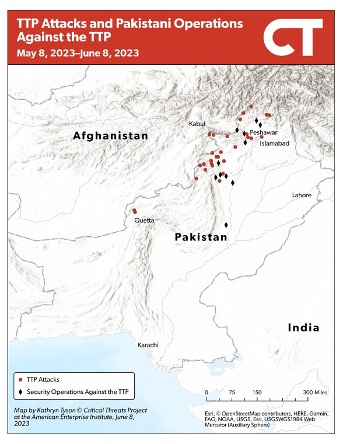

The infographic reinforces how TTP attacks and corresponding Pakistani counter-terrorism operations against TTP have mostly focused across the Pakistan-Afghan border regions, with a pre-eminent focus on KP and Balochistan.15

Such terrorism places pressure on an already tenuous rapport between Pakistan and Afghanistan. Prime Minister Anwaar-ul Haq Kakar stated on 8 November that terrorism augmented in Pakistan ever since the interim Afghan Taliban government captured the reins of power in 2021. He also assured that stern retaliation would be initiated against anti-Pakistan groups, especially the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan, and they will not be permitted to use Afghan territory against Pakistan.

When the Afghan Taliban took over Kabul, several commitments had been made to the US and coalition forces. Two of their main pledges were essential in the Doha Accords: firstly, that Afghanistan’s soil would not be utilized against any other nation. The other fundamental commitment was that an all-inclusive consensus government would be formed in Afghanistan. As the coalition forces departed, the Afghan Taliban refrained from inviting other political factions to forge an inclusive consensus government. Futhermore, militants such as the TTP burgeoned under their watch.

Meanwhile, the TTP pledged allegiance to the Afghan Taliban’s chief Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada. The interim Afghan Taliban regime offers them safe sanctuary, especially in Afghanistan’s Eastern belt of Paktika, Paktia, Kunar, Khost and Nangarhar provinces, among others.

There is video footage depicting TTP’s lead, Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud, in Afghanistan’s Kunar province guiding fighters in Pakistan’s Chitral16 district, which in September witnessed deadly TTP assaults. Nonetheless, the Afghan Taliban obstinately refuse to admit this presence. When Pakistani delegates negotiated with TTP leaders, the TTP’s top cadre were in Kabul. The Afghan Taliban leaders consistently insisted that they were “facilitating talks” between the TTP and Pakistan. During this time, multiple extremists were released as a goodwill gesture by the former government of Pakistan. However, post negotiations, some militants were seen stirring trouble/violence in Swat.

The recent surge in terrorism is arguably linked to the coalition forces’ Afghanistan withdrawal. Previously, Pakistan received international aid in combating terrorism, in the form of Coalition Support Funds, but South Asia is no longer a focal point for the West, especially the US and allied forces.

TTP, ISKP and Baloch Separatists – An Unholy Trinity for Pakistan

Although a revitalized Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) reportedly orchestrated a Herculean chunk of recent terrorist attacks in Pakistan, the increasing presence, and actions of the self-styled Islamic StateKhorasan Province (ISKP) group are equally disconcerting. Several recent militant operations have been linked to the ISKP death cult, who notoriously masterminded the JUI-F political rally Bajaur blast in July 2023. Despite no formal claims, the Mastung suicide attack in September 2023 bears resemblance to an ISKP assault. ISKP are a hardcore Salafi organization who violently oppose the Afghan Taliban and JUI-F, considering them as lightweight Deobandi outfits, not following the true path of (their distorted version of) Islam.17

IS in Pakistan have two local affiliates — the Islamic StateKhorasan Province (ISKP) and the Islamic State in Pakistan Province (ISPP) introduced in 2019. Some former TTP extremists defected from TTP, dismissing them as too “soft-core”, and joined ISKP or ISPP.18 Many of them are Salafi or espouse to highly divisive anti-Shia sectarian inclinations. These mainly come from several sections of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), including Orakzai, Bajaur, Kohat, and South Waziristan. The second group consists of former extremists from the now outlawed militant outfit Lashkari-Jhangvi (LeJ), an anti-Shia militant group, predominantly from Balochistan’s Mastung, Quetta, Nushki and Khuzdar regions, as well as parts of northern Sindh.

On 14 September 2023, IS claimed responsibility for a bomb detonation which struck a Jamiat-e-Ulema Islam-Fazl (JUI-F) rally, a religious political party, in Joto, Mastung district. The heinous attack injured 11 people, including the party’s former senator, Hafiz Hamdullah.

IS in Pakistan also claimed responsibility for the killing of a levies officer and injuring another in Bus Adda on 7 September, only days after the assault targeting a policeman near Wali Khan police station on 26 August. In another incident, on 12 August, the terror group claimed to have killed a policeman in the Kanak area,19 signalling a concerning escalation in ISKP/ISPP terror activities.

ISKP’s/ISPP’s eventual aspiration in Pakistan is to topple the government and its neighbours, erecting a transnational caliphate. Its ambition is highly sectarian and global, whereas TTP is more concerned about and contained to Pakistan itself. ISKP targets non-Sunni Muslims (including Shia and Sufi Muslims), Sikhs, and Christians in Afghanistan and Pakistan and are sworn enemies of the Afghan Taliban,20 whom they accuse of being hateful nationalists. They condemned their negotiations with America, labelling them as “sell-outs” after the Doha Accord. ISKP also increased its anti-China stance and has assaulted Chinese interests in Pakistan.

ISKP attacks in KP have also escalated noticeably. Over the past few months, the terror group has claimed responsibility for multiple atrocities in the North-Western province. It asserted responsibility for a July suicide bombing at a JUI-F political rally in Bajaur district bordering Afghanistan, claiming at least 54 lives. Bajaur has since ages been a shelter for extremists, including TTP and ISKP.21

Such newer confrontations in Bajaur partially stem from the conflict between ISKP and the Afghan Taliban in Afghanistan. Numerous Afghanistan based JUI participants, previously fighting shoulder-toshoulder with the Afghan Taliban, have returned following the war’s conclusion. The confrontation has now spilled over to other locations in KP and Balochistan, injecting a new dynamic into the ever-evolving terrorism landscape.22

The evolving alliance between certain TTP units and ISKP is deeply troubling. Some dossiers hint at a tactical collaboration amongst certain Baloch separatists, ISKP/ISPP and TTP. The BalochTTP connection is already set in motion. In December 2022, Mazar Baloch’s Makran division joined TTP. In June, the Aslam Baloch faction from Noshki district pledged allegiance to TTP’s head Nur Wali Mehsud. This partly explains why the Baloch separatists have not adversely reacted to TTP’s ingress in Balochistan. This lack of reaction is taken as a tacit approval of an entente reached between TTP and Baloch separatists. The Baloch separatists’ adoption of suicide terrorism is the result of training given by TTP in its training camps in Eastern Afghanistan. Lastly, TTP has overtly articulated empathy with Baloch ethnic grievances in its propaganda rhetoric. Nur Wali, in his book, Inqilab-e-Mehsud, commented that during TTP’s glory days, not fostering collaboration with Baloch separatists was an oversight.23

Such an amalgamation of diverse extremist entities complicates matters for the army, law enforcement agents and counter-terrorism departments. Figures suggest that post-Taliban takeover there has been a surge in IS-K combatants in Afghanistan, drawn from other transnational terrorist factions. This reality represents a danger beyond Afghanistan.

ISKP’s risk to Pakistan cannot be downplayed, given the escalating militant events in the nation. ISKP seeks to, amongst other things, lure terrorists from competing rivals so they can strengthen their footprint in Pakistan. Their key target for recruitment is TTP. ISKP blamed TTP for leaving their terror campaign after having declared a ceasefire with the Government of Pakistan (GoP) in December 2021.24 Many TTP extremists were against these talks to begin with and tied the knot with ISKP. A similar outcome happened with the Afghan Taliban, whose disenfranchised extremists became members of ISKP after the Doha Accords.

ISKP’s upsurge intensifies Pakistan’s present problems. ISKP will never be willing to accommodate any views by the GoP due to their hard-core ideological intransigence. Their lack of a centralized decision-making structure in South Asia makes it tougher to pin them down. ISKP’s official communications exhibit a persistent soft spot for the TTP as opposed to their hardline stance towards the Afghan Taliban and GoP. A TTP-ISKP alliance would be deadly for South and Central Asia and further afield.

Islamabad’s over emphasis on the TTP allows more operational maneuverability and tactical advantage to ISKP/ISPP to strengthen their Pakistani presence and profile. The scheduled elections in February 2024 will offer the ISKP death cult another opportunity to carry out conspicuous assaults. Decision-makers, LEAs, CTDs and intelligence agencies must carefully assess such risks and implement preventive initiatives to counter and combat this menace.

EVALUATING PAKISTAN AFGHANISTAN RELATIONS

The Afghan Taliban—Declaratory Rhetoric versus Ground-Realities

In September 2023, the Afghan Taliban reportedly captured and rounded up two hundred TTP militants (with pressure from Pakistan) having been accused of their involvement in cross-border terror attacks and initiated measures to “neutralize” TTP militant activity. However, that was mere declaratory rhetoric rather than a realistic crackdown. There has been no reduction in militant attacks, quite the opposite. As these recent months and the whole year of 2023 attest, hundreds of innocent Pakistani civilians and security forces lost their precious lives, largely due to TTP (and to an extent ISKP/ISPP) terrorism.

After a fiery exchange of diplomatic and public statements between Pakistan’s top civilian and military brass and the Afghan Taliban—the former expressed “grave concerns”25 to the Afghan Taliban government regarding the participation of Taliban fighters alongside the TTP in carrying out attacks across Pakistan— a Fatwa (religious decree) was passed by the supreme leader (Emir) of the Afghan Taliban, Sheikh Haibatullah Akhundzada, urging the TTP that any “Jihad” against Pakistan is “haram” (a non-permissible sin) as it contravenes the laws of Shariah.

However, what has largely gone unreported and unnoticed is that the spokesman for the Afghan interim government, Zabihullah Mujahid,26 maintaining a low-profile, conjured up a clarification, opportunistically denying that the Fatwa had been issued by their supreme leader himself.

Zabihullah Mujahid reasoned that edict was actually issued by the Dar-al-Ifta, a Taliban-run Institute of Islamic Jurisprudence27 (Usul-ulFiqh) which issues Sharia based decrees. Edicts by the Dar al-Ifta of the Islamic Emirate are not orders but rather a fatwa of the institute.28

In addition, there is no specific mention of the TTP in the Fatwa. It carefully dodges citing the TTP,29 not even indirectly implying that it might be parenthetically aimed at the TTP. Thus, this U-turn once again indirectly gives TTP an insidious carte blanche to attack Pakistan. In fact, the fatwa orders the Afghan Taliban not to join the armed struggle in foreign countries, including Pakistan, or take part in operations carried out by the TTP. Yet the TTP have reduced this Fatwa to a paper tiger, showing their selective “pick and choose” policy when it comes to religious doctrine.

In the aftermath of Zabihullah Mujahid’s clarification, TTP wasted no time in releasing a circular: “Zabihullah Mujahid has explained that no such Fatwa (preventing TTP from targeting Pakistan) has been issued by the Emir ul Momineen, Sheikh Haibatullah Akhundzada”.30 TTP then reinforced their allegiance to the Islamic Emirate as an obligation. Such obfuscation allows the TTP “get-out clauses” from their commitments to the Emir, while proceeding with their bloodlust.

Such machinations reveal a duplicitous insincerity and hypocrisy. Such actions are what sour their relations with Pakistan and the international community.

One reason the Afghan Taliban delivers conflicted commitments, seem incoherent and do not follow-up on their word is that they are internally fragmented. A reason why the Afghan Taliban has not devoted its significant time, resources and attention to militants within Afghanistan is due to their own internecine infighting, squabbles and quarrels. The Taliban never evolved from a guerrilla force into a functional government (hence remain unfit to rule).

The Taliban, comprised primarily of Pashtuns, is divided along ethnic, regional, and tribal lines. There are also policy divergences. There is mounting competition between the Haqqani network based in Eastern Afghanistan versus a faction of Taliban co-founders in the South of the country. There is also a smaller and less powerful faction of ethnic Tajik and Uzbek Taliban commanders who are based in northern Afghanistan31. There are also fissures between the Taliban’s more pragmatic figures, hard-core field commanders (strong in rural areas), and extremist clerics who are bent on implementing their version of Shariah law.

Pakistan’s Escalating Pressure Campaign

The rapport between Islamabad and Kabul is about to plummet further given Pakistan’s escalating pressure campaign and the Taliban’s unwavering support for the TTP. The Afghan Taliban’s top brass has negated Islamabad’s legitimate qualms on the TTP, casually and brazenly labelling it as Pakistan’s “domestic issue”.32 By labelling the TTP as a domestic issue in Pakistan, the Taliban leadership negligently sidesteps Pakistan’s credible concerns.

In a presser on 8 November 2023, Anwar ul-Haq Kakar, the care-taker PM of Pakistan, gave a scathing indictment of the Taliban government in Afghanistan.33 He declared that since the Taliban took over Afghanistan in August 2021, over 2,800 Pakistanis lost their lives due to the TTP’s anti-Pakistan terror campaign, which got backing by the Afghan Taliban leadership.

Even though there has been proof of the Afghan Taliban’s support for the TTP, in the form of safe sanctuaries and material aid, the Pakistani government has been previously cautious in its portrayal of the relationship since the Taliban took over in August 2021. This time, PM Kakar abandoned softer diplomacy and asserted that there was “clear evidence of [the Taliban] enabling terrorism” by the TTP, albeit “in a few instances.”34 PM Kakar further stated that “since the Taliban’s return to power, terrorism in Pakistan has surged by 60 percent and suicide attacks by 500 percent, killing over 2,300 people.” In addition, he asserted that of the “24 suicide bombings witnessed in Pakistan in 2023, 15 were carried out by Afghans.”35 Asif Durrani, Pakistan’s special envoy to Afghanistan, commented on Kakar’s criticism of the Taliban a few days after the speech, saying that “peace in Afghanistan, in fact, has become a nightmare for Pakistan.”

Pakistan has launched a wider pressure campaign in accordance with the new policy to persuade the Taliban to re-evaluate and renege their TTP backing. The expulsion of illegal migrants is part and parcel of this pressure tactic. Repatriation of 1.7 million undocumented Afghan refugees from the country has been set in motion. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) confirmed that 327,000 refugees36 have been directed to leave Pakistan en route back to Afghanistan.

Recently, Taliban Prime Minister Hassan Akhund urged Pakistan’s government and “military” to follow “Islamic guidelines”. A statement from the group’s supreme leader, (Emir) Hibatullah Akhundzada, voiced concern over the treatment of undocumented Afghan refugees. Pakistan has also been cautioned by the Acting Taliban Defence Minister, Mawlawi Muhammad Yaqoob Mujahid, to consider the “consequences” of its actions and to remember that it will reap what it sows. Mr Yaqoob staunchly critiqued the treatment of Pakistan’s caretaker government towards Afghan refugees. In an audio clip, Mujahid called on Pakistan’s authorities to not “be cruel to the Afghans, not seize their personal property and assets.” “They cannot do it by any law or rule. Such actions will be questioned. We will attempt with all our capacity to prevent it and will not allow anyone to seize and steal the personal property of our Afghan brothers.” He urged the global community, UN and other entities to pressure Pakistan to end “the current situation towards the refugees.”37

The intensity of the Afghans’ and Taliban members’ rage over Pakistan’s repatriation of Afghan refugees is partially voiced in these declarations made by Taliban’s top brass. Following the collapse of the TTP-Pakistan talks that the Taliban had mediated last year, Taliban leaders have expressed exasperation over Pakistan’s increasing pressure on them as well as Islamabad’s (understandable) outright disinclination to engage in negotiations or make any kind of concession to the TTP.38 Interestingly, the alignment of leaders from various divisions and units within the Afghan Taliban on this matter provides valuable insight into Afghan domestic politics indicating that they may be reaching a consensus regarding their anti-Pakistan stance.

Pakistan is also prepared to intensify economic leverage to force the Taliban to reconsider their backing of the TTP. Pakistan’s economic clout stems in part from its location as the primary transit route for commerce between land-locked Afghanistan and the Taliban-led state. Over 40% of Afghanistan’s customs revenue comes from border crossings with Pakistan; this accounts for almost 60% of the Taliban’s overall profits and returns. Pakistan has tightened the economic belt on regulations for transit trade, placed strict bank guarantees on Afghan importers (often accused of underinvoicing), increased the category of products Afghanistan is not permitted to import through Pakistan, and levied 10% processing fees on key commodities that Afghanistan imports.39 Not only has all such activity curbed Pakistan’s ‘informal economy’, bringing many smugglers under the tax-bracket, it has also strengthened the Rupee which has appreciated from PKR 325 against the US dollar in July 2023 to PKR 286 versus the U.S. dollar.

According to the Taliban, Pakistan has also decelerated and reduced the flow of containers reaching its ports (Karachi, Qasim, Gwadar) from Afghanistan. Pakistan’s economy will be somewhat impacted by these initiatives, but it is not as dependent on the Afghan economy as it once was. Pakistan used to import a considerable amount of coal from Afghanistan, but that has decreased as global coal prices have plummeted. Pakistan has opted for South African and Indonesian coal. All in all, consequently, by reducing its income and trade volumes, Pakistan’s actions will exert more pressure on an increasingly alienated Taliban40 government. Pakistan still has other options to exert more economic pressure, such as blocking, sealing or disrupting border crossings to cut off Taliban’s revenue base.

If economic strategies prove ineffective, Pakistan may resort to a more aggressive approach, as a very last resort, which includes conducting cross-border military operations (trough air power/drones41) targeting TTP’s senior cadre and training/camps in Khost, Kunar, Ghazni, Paktika, Paktiya, Nangarhar, Nuristan and in Afghanistan’s eastern regions. Yet this would be a very last resort.

Such measures are a last option, as they would intensify hostility towards Pakistan in Afghanistan, bolster support for the TTP there, and provoke revenge attacks. Nevertheless, such cross-border kinetic actions may compel the Taliban to reconsider their stance with TTP, at least temporarily, as seen previously when Pakistan’s airstrikes in April 2022 prompted the TTP to agree to a ceasefire, under pressure and influence from the Afghan Taliban.

Furthermore, Islamabad has to intensify its regional diplomatic charm offensive to counter the intransigent Taliban and limit the operational manoeuvrability of the TTP. Islamabad must foster more intense relations with neighbouring/nearby countries in Central Asia and Iran to regionally resist terrorist influence from within Afghanistan42. After all, this is the strategy Taliban is deploying to counterweight Pakistan. Recent attempts by Taliban Deputy Prime Minister Abdul Ghani Baradar to secure increased port entry (especially Bandar Abbad Chabahar) and trade discounts from Iran highlight this strategy, aiming to reduce reliance on Pakistan for transit trade.

To counter-weight Islamabad’s recent pressure, Kabul can attempt to diversify its foreign policy alliances and options. Such a foreign policy strategic rebalancing act would aim at influencing Islamabad to cave into compromises on TTP43 and other factors. The Taliban could seek rapprochement with Central Asian Republics, India and Iran to better shoulder the weight of the current jolt they received due to Pakistan’s migrant repatriation, tightening transit trade and anti-smuggling measures. On 4 November 2023, a Taliban delegation arrived in Tehran where both countries bilaterally signed economic collaboration pacts in civil aviation, transportation, mining and free trade and economic zones.44

In 2016 India-Iran-Afghanistan forged a partnership, involving $8 billion investment in Chabahar port and industries in Chabar Special Economic Zone. Though Chabahar port has lost its lustre45 compared to Gwadar, it seems as if Afghanistan is trying to influence Iran to try and reactivate the Chabahar port as it is a transit route to Afghanistan and Central Asia. However, the extent to which Iran can serve as a comprehensive alternative remains uncertain.

To leverage on Islamabad’s perceived apprehensions, the Taliban may also try to strengthen ties with India, and grant India trade concessions in return for financial support. India has restarted work on stalled infrastructure projects46. New Delhi also carries on offering humanitarian relief to Afghanistan47, especially medical and food aid for the Afghan people. The BJP government has partnered with United Nations World Food Programme (UNWFP) for internal distribution of wheat.

Keeping in mind the hawkish sentiments reverberating from Afghanistan towards Pakistan (especially after the policy to expel all illegal migrants) and the influence that may be asserted by hostile countries, the strategy to escalate extremist activity in Pakistan using proxies may be employed.

This would be an unwise course of action by the Taliban. The use of terror will not result in the desired change in Pakistan’s conduct. Even if more attacks occur, representing additional economic strain, it’s very improbable that these will compel Islamabad to resume talks with the TTP.48 As a matter of fact, such attacks will prompt Pakistan to exercise added pressure on the Taliban instead.

The alternate option is that the Taliban may try and communicate with Pakistan through a diplomatic backchannel. Previously, the Taliban have relied on pro-Taliban Pakistani decision-makers to defuse tense situations with Afghanistan. The Taliban can also request assistance from a few foreign parties to defuse the situation. Qatar is the most accessible and well-positioned nation to act as an independent peace broker and mediator49 between Pakistan and the Taliban. China may attempt to mediate as well, but it may share Pakistan’s viewpoint on the growing insecurity in Pakistan and has its own security concerns regarding militant factions based in Afghanistan, most notably the Turkistan Islamic Party with a presence in Badakhshan Province.

The Need of a Holistic Approach to Counter Terrorism in Pakistan – 2024 and beyond

As political and economic uncertainty engulf Pakistan, terrorists of all hues and stripes are poised to exploit and wrongly take advantage of the situation. The most current cycle of terrorism has once again exposed the need of a cohesive policy as security forces tenuously grapple against the audacious extremist assaults that have claimed the precious lives of scores of security personnel and innocent civilians, especially soaring in 2023.

The pressing imperative rests on devising an effective and sustainable counterterrorism strategy to eliminate and downgrade all threat vectors endangering the nation’s precarious and fragile security. Pakistan must urgently re-evaluate its national security policy50 to rectify the flaws that have led to this dire situation. Good starting points would be to re-activate National Counter-terrorism Authority of Pakistan (NACTA) vesting with it the power it requires for enforcement, upgrading and revising the 2014 National Action Plan which has to be made more comprehensive and current as well as fully empowering Federal and recently formed Apex Committees to initiate bold and decisive action to counter violent extremism (CVE).

Additional holistic counterterrorism measures should include:

- Community Engagement: Strengthen community resilience51 programs to embolden trust between law enforcement agencies and local communities, encouraging and incentivizing local stakeholders’ cooperation with Suspicious Activity Reporting (SAR). This is a truly whole-of-society approach to preventing violent extremism (PVE).

- Countering Financing of Terrorism: The economic levers Islamabad deployed is a great starting point. However much more needs to take place, on a forensic and audit trail level for the Countering Financial Terrorism (CFT) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) milestones complemented by Pakistan’s 2010 Anti-Money Laundering Act and Financial Monitoring Units (FMUs) to be effective.

The National Accountability Bureau (NAB), the Anti-Narcotics Force (ANF), the Directorate of Customs Intelligence and Investigations (CII), and the Federal Investigative Agency (FIA), the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) and the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP) all have a pivotal co-ordinated role to play. They must enhance their efforts to track and disrupt the financial flows and funding sources of terrorist organizations by enforcing anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing laws.

- Capacity Building: Invest in the capacity building, training, joint kinetic drills of law enforcement agencies, intelligence services, and judicial systems to effectively combat terrorism.

- International Cooperation: Strengthen collaboration with neighbouring countries and international partners through intelligence sharing and joint operations to tackle transnational terrorist threats.

Pakistan Afghanistan Relations into 2024 and beyond

Afghanistan must discard the deep misgivings that choke the enormous potential for collaboration due to its geo-strategic positioning as a bridge between South and Central Asia. The existing chasm must be bridged between Islamabad and Kabul. The repatriation of 1.7 million52 unregistered migrants back to Afghanistan will taint bilateral relations for a while but eventually those departed migrants will be re-integrated into Afghan society. No doubt, this will take time.

The Taliban needs to move away from finger-pointing and blame-games and start ruling Afghanistan with governance and institutional resilience; for that the Taliban have to mature from an insurgency into a functional government. Here again many countries can help the Taliban with governance, institution and capacity building. The Taliban must let go of their hubris and request the global community for help in rebuilding Afghan institutions.

Pakistan, 76 years back was a new state born into arduous conditions including bitter neighbors (both on the Eastern and Western borders) characterized by cut-throat power contests. Pakistan’s relationship journey with its western neighbor is characterized by socio-political cataclysms. Despite substantial historic, demographical, cultural and trade relations between and amongst a significant Pakistani and Afghani population, the ongoing mutual resentment between the states has frozen bilateral rapport and is ill-disposed to yielding resilient friendly relations. In previous decades, Islamabad and Kabul’s rapport wavered to excesses.

For now, given Islamabad’s tense relations with Kabul, it must tread cautiously on shifting geopolitical sands, where a ‘handshake’ with the Taliban will suffice, for an ‘embrace’ is highly unrealistic, with a predominantly difficult yet co-dependent rapport between the neighbours. Urgent issues carry on shaping the bilateral Af-Pak rapport: the inflow into Pakistan of millions of (largely undocumented) Afghan migrants53, the safe-havens TTP exploit and enjoy in Afghanistan, Kabul’s non-acceptance of the Durand Line, their ongoing shielding of TTP terrorists, and misuse of the transit trade routes contravening Pakistani laws.

Despite escalating tensions, especially at the border regions, caretaker Prime Minister Anwaar-ul-Haq-Kakar wrote a letter to his Afghan counterpart, Mullah Hassan Akhundzada, advising that both countries must work on common goals54 of which there are many. Despite shortcomings, come what may, Pakistan has close fraternal relations with Afghanistan rooted in culture, history, and shared faith. Kakar said Islamabad is determined to strengthen bilateral trade and security ties with the Taliban government.

At present, despite Kabul’s persisting criticisms against the repatriation of undocumented Afghans55, Afghanistan’s Minister of Commerce and Industry, Nooruddin Azizi, met with Pakistan’s foreign minister, Jalil Abbas Jilani in Islamabad for the trilateral Pakistan-Uzbekistan-Afghanistan trade negotiations. According to Mr. Azizi`s statement, a trilateral technical group will meet to identify methods to grow regional trade via joint investments and enhanced trade transit services. This is the regional economic connectivity promise and potential that Kabul, Islamabad and Tashkent must capitalize on.

Pakistan-Afghanistan rapport has almost always been volatile with both sides at loggerheads. Seventy-six years later56, the tendency of swinging between engagement and hostility continues.

Despite all the above, bilateral trade negotiations are still ongoing, including key talks on transit trade, an economic lever and overture which Islamabad is using to maximum effect. The uneasy incongruity of collaboration and clashes will carry on shaping Af-Pak bilateral relations into the foreseeable future.

The sixteenth Tashkent ECO summit provides a concrete example of Islamabad and Kabul swinging between engagement and hostility; between collaboration and confrontation as the norm57. The paradox of undue tension and extreme inter-dependence of this relationship was seen in practice. Within just a span of one day, care-taker PM Kakar brazenly offered Kabul an ultimatum: to choose between either Islamabad or TTP terrorists in Afghanistan. The very following day, PM Kakar talked of Afghanistan’s key role in the achievement of regional connectivity, as a bridge between South and Central Asia. Seasoned diplomats from both sides of the border are fully accustomed to a bitter-sweet foreign policy between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Navigating judiciously across contradictions in a holistic manner is at the core of enhancing Pakistan’s relations with Afghanistan. Pakistan understands the centrality of its relations with Afghanistan58 for trade, commerce and security. It must accordingly steer bilateral and regional relations forward going into 2024 and beyond.

Epilogue

Pakistan and Afghanistan are undergoing trials and tribulations as seldom seen before. Relations have always been patchy yet this is a new low. Islamabad made diplomatic overtures when in October 2023 Afghanistan underwent a devastating earthquake in Herat. Pakistan offered to help only to have their offer dismally rejected.

The constant invoking of a spectre of a New Cold War between Islamabad and Kabul especially by pundits and the media for sensationalism is unhelpful and it encourages a disproportionate knee-jerk response. Afghanistan and Pakistan, through third party intermediaries, back-channel diplomacy, well-meaning mediation, regional geo-economic connectivity and mutual interests must find a way to co-exist, a modus vivendi of sorts.

Conceded, the above will take time, yet it is better than nay-sayers constantly stoking bilateral fear which will neither help Islamabad nor Kabul to propel us along a path of bilateral resilience. In South Asia, as a general rule of thumb, we desperately need a cooling of rhetoric and an injection of cool-headed statesmanship. All sides will need to give and take, discard their ideological intransigence and tribal myopia to collectively move forward.

References

- Baqai, Huma and Nausheen Wasi (2021) Pakistan-Afghanistan Relations: Pitfalls and the Way Forward, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, September, 2021.

- Siddique, Abubakar and Majeed Babar (2023) Pakistan Taliban attempts land grab to boost insurgency against Islamabad, Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, 16 September, 2023.

- Gul, Ayaz (2023) Suicide bombings, militant raid kill 62 in Pakistan, Voice of America, 29 September, 2023.

- Gul, Ayaz (2023) Surge in Terrorism kills more than 700 Pakistanis, Voice of America, 30 Sep, 2023.

- Hussain, Zahid (2020) Regional militant sanctuaries, Dawn, July 29, 2020.

- For more https://www.geo.tv/latest/512538-information-minister-warns-ofbefitting-response-if-india-behind-deadly-mastung-blast

- Balochistan government moves to rein in terrorism (2023) The Nation, October 2, 2023.

- ibid

- ibid

- Islamabad, Kabul should work together, Pakistan PM Kakar tells Afghan counterpart amidst border tensions. Islamabad, Kabul should work for common goals, Pakistan PM Kakar tells Afghan counterpart amidst border tensions (2023) Deccan Herald, 18 September, 2023.

- View the D.I. Khan Economic Zone website at https://kpezdmc.org.pk/DIKhanEZ

- Pakistan army battles Taliban for strategic Tirah valley, Agence France Press, 4 April, 2015.

- Appraise: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/pakistan/supportpakistan%E2%80%99s-action-counter-terrorism-special-reference-khyberpakhtunkhwa-pact-kp-project_und_kk?s=222

- McGovern, Glenn P. (2012). “Securitization After Terror”. In Margaret E. Beare (ed.). Encyclopedia of Transnational Crime and Justice. Sage.

- Tyson, Kathryn (2023) Critical Threats Project, American Enterprise Institute, 8 June, 2023

- Hussain, Abid (2023) Four soldiers, 12 TTP fighters killed in Northwest Pakistan, Al-Jazeera, 7 September, 2023.

- Palmer, Alexander and McKenzie Holtz (2023) The Islamic State threat in Pakistan: trends and scenarios, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 3 August, 2023.

- ibid.,

- Rehman, Ur Zia (2023) Inside Balochistan`s sectarian shift – the rise of IS from Lashkar-i-Jhangvi, Dawn Prism, 3 October, 2023.

- Sikandar, Ayesha (2023) Assessing ISKP`s expansion into Pakistan, South Asian Voices, 25 September, 2023.

- Islamic State Khorasan claims responsibility for deadly suicide bombing in Pakistan (2023) Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, 01 August, 2023.

- Jadoon, Amira, Mines Andrew and Abdul Sayed (2023) The enduring duel: Islamic State Khorasan`s survival under Afghanistan`s new rulers, Combating Terrorism Centre (CTC Sentinel) at Westpoint, August 2023, Volume 16, Issue 8.

- Khan, Basit Abdul (2023) Is there a Baloch separatist-Pakistan Taliban nexus: Separating fact from fiction, Arab News, 27 January, 2023.

- Refer to: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https:// www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/sr-520-growing-threat-islamic-stateafghanistan-south-asia.pdf

- Go through https://www.rferl.org/a/azadi-briefing-afghan-taliban-pakistanjihad-indonesia-refugees/32656456.html

- See https://www.rferl.org/a/azadi-briefing-afghan-taliban-pakistan-jihadindonesia-refugees/32656456.html

- More at https://tolonews.com/afghanistan-184593

- Adib, Fatima (2023) Darul Ifta issues Fatwa prohibiting Afghans from war abroad: Mujahid, Tolo News, 11 August, 2023.

- See https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2023/04/14/ttp-led-terrorism-is-unislamic/

- View https://www.voanews.com/a/afghan-taliban-chief-deems-cross-borderattacks-on-pakistan-forbidden-/7213760.html

- For in-depth details on internal divisions: https://www.rferl.org/a/taliban-riftsexposed-afghanistan/31880018.html

- Evaluate https://www.mei.edu/publications/pakistan-afghan-taliban-relationsface-mounting-challenges

- View: https://www.voanews.com/a/pakistan-to-taliban-ruled-afghanistanchoose-bilateral-ties-or-support-for-militants-/7346720.html

- Analyse https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-asia/afghanistan/afghanistanssecurity-challenges-under-taliban

- Review: https://thediplomat.com/2023/11/pakistans-new-afghan-policyanother-disaster-in-the-making/

- OCHA (2023) : 327,000 Afghans returned from Pakistan since mid-September, Tolo News, 16 November, 2023.

- Stanikzai, Mujeeb Rahman Awrang (2023) Acting Defence Minister warns Pakistan against “cruel” treatment of Afghans, Tolo News, 3 November, 2023.

- https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Afghanistan-turmoil/ Taliban-warns-Pakistan-about-Afghan-expulsions-Reap-what-you-sow

- chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.usip.org/ sites/default/files/2021-08/pw_175-afghanistan_pakistan_ties_and_future_ stability_in_afghanistan.pdf

- For more on Pakistan`s economic belt-tightening: https://www.arabnews.pk/ node/2387031/pakistan

- On the effectiveness of drones: https://tnsr.org/2022/01/were-drone-strikeseffective-evaluating-the-drone-campaign-in-pakistan-through-captured-alqaeda-documents/

- https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-asia/pakistan/pakistani-taliban-test-tiesbetween-islamabad-and-kabul

- Ahmed, Samina (2023) The Pakistani Taliban test ties between Islamabad and Kabul, The International Crisis Group, 29 March, 2023.

- Aktas, Alperen (2023) Iran, Afghanistan sign 5 key economic agreements, Anadolu Agency, 10 November, 2023.

- Aliasgary, Sourosh and Marin Ekstrom (2021) Chabahar Port and Iran`s strategic balancing with China and India, The Diplomat, 21 Oct, 2021.

- The emerging role of India in Afghanistan: Pakistan`s concerns and policy response (2023) Pakistan Institute for Peace Studies (PIPS), 2 May, 2023.

- The India Pakistan rivalry in Afghanistan https://www.usip.org/ publications/2020/01/india-pakistan-rivalry-afghanistan

- Sayed, Abdul and Tore Hamming (2023) The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan after the Taliban`s Afghanistan takeover, Combatting Terrorism Centre at Westpoint, CTC Sentinel, May 2023, Volume 16, Issue 5.

- Salami, Mohammad (2021) Navigating Influence in Afghanistan: the Cases of Qatar and Pakistan, Fikra Forum, Washington Institute, 26 Oct, 2021.

- To read Pakistan`s entire National Security Policy (2014-2018) http://nation.com.pk/islamabad/27-Feb-2014/text-of-national-securitypolicy-2014-18

- Mirahmadi, H. (2016) “Building Resilience against Violent Extremism: A Communitybased Approach,”the ANNALS of American Academy of Political and Social Science 668, 129-144, (2016).

- Ali, Mushtaq and Mohammad Yunus Yawar (2023) Pakistan speeds up Afghans` repatriation as deadline expires, Reuters, 3 November, 2023.

- Hussain, Zahid (2023) Pakistan`s forced expulsion of Afghan migrants has brought bilateral relations to breaking point, Arab News, November 12, 2023.

- Islamabad Kabul should work for common goals, Pakistan PM Kakar tells Afghan counterpart amidst border tensions (2023) Times of India, September 19, 2023.

- Sajid, Islamuddin (2023) Afghan minister raises refugee issues with Pakistani officials in Islamabad, Anadolu Agency, 14 November, 2023.

- Baqai, Huma and Nausheen Wasi (2021) Pakistan-Afghanistan Relations: Pitfalls and the Way Forward, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, September, 2021.

- Islamabad, Kabul should work together, Pakistan PM Kakar tells Afghan counterpart amidst border tensions. Islamabad, Kabul should work for common goals, Pakistan PM Kakar tells Afghan counterpart amidst border tensions (2023) Deccan Herald, 18 September, 2023.

- Threlkeld, Elizabeth and Easterly, Grace (2021) Afghanistan-Pakistan ties and Future stability in Afghanistan, United States Institute of Peace, Number 175, August, 2021.