Abstract

(Terror attacks proliferated in Pakistan ever since the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul, deteriorating already strained relations between Islamabad and Kabul. Actionable steps are recommended in this paper, involving both hard and soft power1, to confront terrorism’s seemingly never-ending generational menace. – Author)

From crushing poverty to an attrition in the state’s institutional capability, to climate change and natural disasters, to venomous mob attacks against Christians, to abductions, assassinations, sectarian extremist outbursts; Pakistan teeters on a razor`s edge of volatile mayhem. Add to this the lack of literacy, a population explosion2, a foreign policy in disarray, a constitutional crisis, election delays and uncertainties and a fragile democracy on tenterhooks; Pakistan is being challenged in the worst of ways imaginable.

As if Pakistan did not already have enough on its proverbial plate, compounding all these problems is an unsafe and unreliable Afghanistan. Since the Taliban warmed the seats of power in Kabul two years back on August 15, 2021, terrorist attacks in Pakistan amplified by an astronomical 73%. The number of victims killed in the attacks in Pakistan from August 2021 to April 2023 (21 months) alarmingly increased by 138%3. The Taliban command spurred extremists operating from (mostly Eastern Afghanistan) furnishing them with safe sanctuaries animating them to augment cross-border attacks in Pakistan.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan particularly experienced a troubling rise from the impact of Afghan`s fragile faltering state and terrorist violence, where the plethora of attacks during these 21 months surged by 92% and 81%, respectively. Conversely, the amount of extremist attacks in Punjab, Sindh and Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT) illustrates a relative downward slope since the Taliban takeover as compared to corresponding 21 months pre-August 20214.

Counterterrorism, public welfare, peace, security and economic policies are cross-cutting and intertwined and must be viewed through a more integrated lens. Economic and political milestones will remain difficult to implement so long as internal security remains compromised, which has added negative impacts on an already volatile political climate.

Pakistan’s National Security Policy (NSP) 2022-2026 revealed in January 2022 merits to be rigorously revised annually. No security policy should have a static timeframe of 4 years as security and counter-terrorism challenges evolve from month to month. The NSP, however, is a move in the right direction—focusing on citizen-centric human security that encourages geo-economics as the bastion for holistic stability. However, political disarray since March 2022 has moved Pakistan further away from materializing the NSP’s vision. Policy continuity has always been a major challenge for Islamabad. Pakistan should chart a course back to the fundamentals of the NSP and embrace human security as a central plank of its counter-terrorism policy. Achieving this, to a great degree, is contingent upon some semblance of political consensus, especially after the national elections likely to be held in early 2024.

The NSP is a creative re-imagining of national security (and counterterrorism) from “state-centric” to “citizen-centric”. Since its immersion in the Afghan War and during the Global War on Terrorism, Pakistan has been involved in long-drawn-out regional conflicts to the intense disservice of its nation-wide development and citizens’ well-being. Such involvement led to the breeding of multiple militant outfits who are now haunting Pakistan’s quest for internal peace and security.

As a “frontline state” and a “major non-NATO ally”, Pakistan decided to assume the role of a regional security guard for extra-regional powers5. The substance of the NSP articulates that Pakistan is no longer seeking to being seen only through the limiting lens of “geopolitics”. It is economic security that would, hereafter, steer the state’s strategic orientation and diplomatic engagements. A welcoming development, as militants such as TTP, AQIS, JuA, BLA, ISKP and others thrive mostly by exploiting poverty and financial vulnerabilities.

Pakistan’s torment of transnational terrorism

In January 2023, the Peshawar police lines mosque blast carnage claimed countless lives shaking the country’s morale to the core. Notorious TTP militants Umar Mukarram Khurasani and Sarbakaf claimed the Peshawar attack via their personal Twitter accounts6 (confirmed by TTP`s propaganda media wing Umar Media) within a couple of hours of the attack.

February witnessed armed extremists target a major police office in the southern coastal city of Karachi in an attack that lasted hours and killed at least seven people7. Another large-scale attack unfolded in the Swat area of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in April 2023 when radicals targeted a counterterrorism office, which tragically resulted in the death of 17 people. July witnessed the targeting of a political rally in Bajaur.

In late August 2023, 11 labourers working on an under-construction army post were ruthlessly killed as a truck exploded with an improvised explosive device (IED) detonated in North Waziristan’s Shawal valley,8 close to the Afghan border.

Attacks by the TTP soared and became ever-more unabashed after the breakdown of its ceasefire with Pakistan’s government in November 20229. The myopic ceasefire was itself a fruitless endeavour by the Pakistani government to terminate the militants fourteen-year war against Pakistan. Unmitigated terror ensued during and after the pretense of a ceasefire.

In the forthcoming two years, complementing and expanding on the Afghan Taliban’s take-over, and gaining resilience and inspiration from it, the TTP’s re-emergence is amplifying. The organization seeks to mirror the successes of the Taliban in neighboring Afghanistan. With a geographical widening of its operations, added mergers, its militants relocating from Afghanistan to Pakistan10, and a highly local focus, the TTP has heightened its terror against the Pakistan state.

The TTP has geographically extended its activities from its major operating theatre in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. By broadening its insidious operations to the Pakhtun area of Balochistan, the banned entity has enlarged the security threat to a province already dealing with unhinged violence by Baloch separatists/militants.

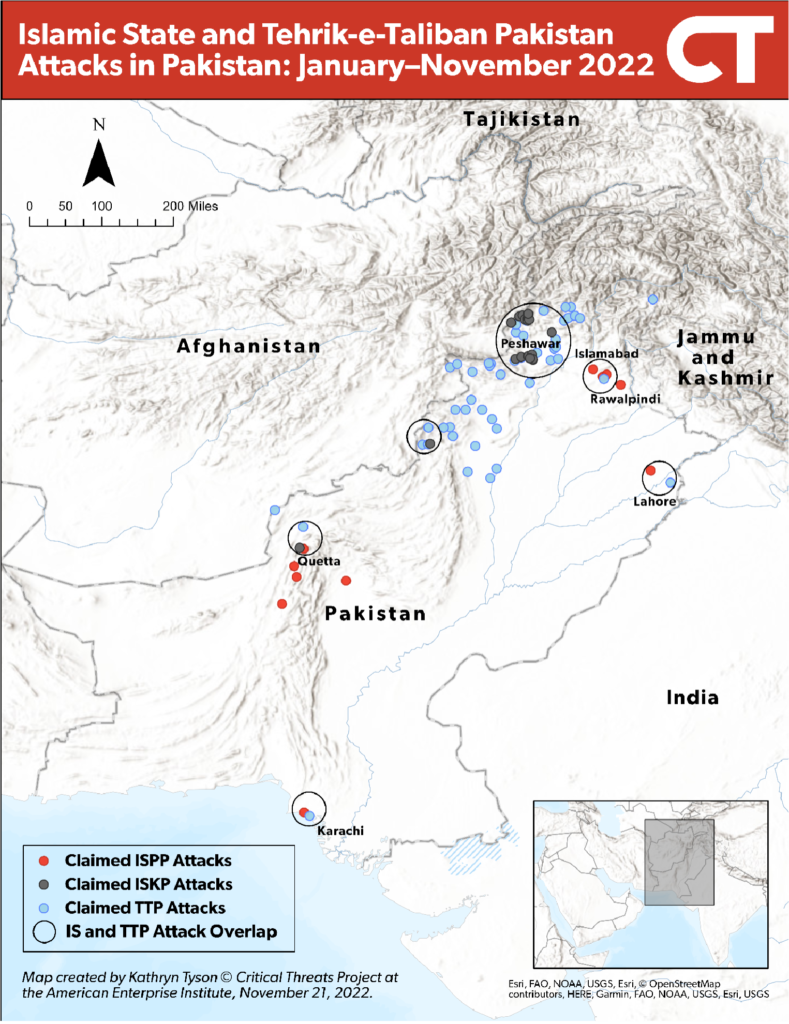

The spate of recent terrorist attacks against Pakistan, spearheaded mostly by the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and by the so-called Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP),11 illustrates that the Afghan Taliban have flagrantly violated most of their own agreed to Doha Agreement which is now nothing more than a symbolic paper tiger unilaterally shredded to pieces.

Though the head of TTP, Noor Wali Mehsud, repudiated12 the reality that the TTP were utilizing Afghanistan’s territory for assaults against targets out of Afghanistan, it is telling that he did not disagree that his terrorists are going on a rampage against Pakistan.

Observations and Implications of the Zhob attack

A recently formed terrorist group labelled Tehreek-e-Jihad Pakistan (TJP), believed to be tied to TTP, has also mounted numerous attacks in Pakistan, recently massacring 12 soldiers and a civilian at a Pakistan army base in the restive southwestern Baluchistan province. Five “terrorists” endeavoured “to sneak into the facility” in Balochistan province’s northern Zhob district, cantonment area13, followed by another deadly attack in Baluchistan’s Sui area, strategically important due to gas reserves and other lucrative mineral and energy resources.

Research is being compiled on TJP; however, it still remains unclear as to whether or not they are part and parcel of a larger extremist group or a separate faction per se. Such factions and splits within ‘TTP and TJP reinforce their fragmented and fluid structures making them nebulous and tougher to track down’.

Three intensely armed combatants allied to TJP/TTP were among some five assailants in the Zhob attack. The ‘Pakistani foreign ministry reported that investigators had specifically identified the three slain Afghans as residents of the southern Kandahar province in Afghanistan’14, and it had requested the Afghan Embassy to receive their bodies.

On July 14, 2023, Pakistan’s army chief, General Asim Munir, declared that he held “serious concerns on the safe havens and liberty of action available to TTP in Afghanistan.” He added, “Such attacks are intolerable and would elicit an effective response from the security forces of Pakistan.” He also claimed that “Afghan nationals were involved in recent acts of terrorism in Pakistan”.15

With the Afghan administration disinclined to act against the TTP, its reorganizing in Afghanistan after the Taliban’s coming to power represents an alarming menace to Pakistan’s security16. Consecutive reports by the United Nations17 Security Council’s Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team observed that the “TTP has arguably benefited the most of all the foreign extremist groups in Afghanistan from the Taliban takeover”.

A recent U.N. Security Council dossier also affirmed that “In June, some TTP contingents were transferred away from the border area close to Pakistan as part of the Taliban’s initiative to restrain and regulate the extremists under pressure from Islamabad”. It noted that up to 6,000 TTP members operate out of Afghanistan, and the Taliban takeover has “emboldened” them18. The U.N. report warned that the TTP could become a regional threat if it carries on enjoying a safe operating base in Afghanistan.

Security forces confirmed that the Zhob19 attack was conducted by five skillfully trained and well-armed militants. The terrorists had night vision goggles (NVGs) along with the most contemporary technology.

With the hasty coalition exit from Afghanistan, the Afghan Taliban carefully sifted all the military ware which remained back by their previous adversaries and put this equipment to use. Photos and videos of Taliban combatants blustering around Kabul, donned in American-made military clothing20, wielding U.S.-manufactured automatic weapons were splashed across multiple media outlets and newspapers after the Taliban takeover.

It is a logical corollary, therefore, that the TTP, who have theological and tactical affinity and rapport with the Afghan Taliban, easily armed themselves to the teeth with the very same plundered bounty and loot of war. The TTP brazenly applies such weapons in its lethal attacks against Pakistani security operatives.

Diagnosing the difference between TTP and ISKP and Pakistan’s forthcoming national elections

ISKP is a Salafi entity put in place by the unholy trinity of TTP, al Qaeda in the Indian Sub-Continent (AQIS), and Taliban combatants who defected from their former organizations in late 2014. ISKP deem the TTP, AQIS and Afghan Taliban to be not hard-liner enough. The ISKP terrorists group mainly operate from Afghanistan, where they are embroiled in a fever-pitched insurgency against the Taliban, and in Pakistan’s KPK, Balochistan21, and, to a lower degree, in Punjab.

Since the 2014 clampdown, the TTP has primarily targeted hard targets such as law enforcement, FC, police and soldiers, mainly refraining from attacking soft target civilians (unlike ISKP). The TTP, eerily emboldened since the Taliban took over, are yearning for relevance and publicity by staging unremittingly inexorable attacks against state security troops. Deluded extremists like the TTP aspire to topple the Pakistani government, destabilise the state and insert their own flavour (and interpretation) of Shariah law in a majorly Muslim nation with more than 241 million people.22

ISKP is motivated by a rationale of outbidding all in the competitive terrorist landscape of an increasingly restive South Asia. ISKP avows itself via lethal large-scale attacks, their trademark since inception. Unlike TTP or TTJ, ISKP is determined by the ideology of its mother organisation ISIL or ISIS—with a few of its combatants trained in Iraq and Syria—which aspires to birth an “Islamic Caliphate” the world over. The TTP (as yet) bear no such aspirations.

ISKP now represents an imminent threat within Pakistan itself. The terrorists purposely target civilians at crowded events such as electoral campaigning which multiplies their chances to wreak maximum havoc. ISKP also poses a grave risk to Taliban members in Afghanistan and retains its global craving to initiate terrorism far and beyond, including in Europe and America, amongst others.

The organization’s yearning for a global footprint remains front and center of their narrative, whereas TTP has a more localized focus (for now). For instance, in mid-2020, an Afghanistan-based virtual planner was suspected of guiding IS, comprising of four Tajiks who were reportedly aiming to attack US and NATO military bases in Germany23. Although the assault never transpired, it is an empirical example of the role ISKP can play in planning or executing attacks against the West. Another reported plot linked to ISKP was uncovered in Türkiye in January 2023, when two militants were placed behind bars. And, in February 2023, following the leak of classified Pentagon documents on the social messaging app Discord, it was reported that US intelligence sources had learned of 15 terrorist plots targeting the West coordinated by ISKP in Afghanistan24.

The terror of the TTP frequently overshadows that of ISKP, which habitually targets civilians. Though ISKP primarily executes attacks in Afghanistan, it is increasingly broadening its territorial relevance and remit by targeting Pakistan, as is apparent after the July 30 Bajaur attack, given its globally expansionist trans-national caliphate agenda.

ISKP also has distinct objectives – the organization aspires to undercut its Taliban arch-enemy by assaulting them in Afghanistan, unlike TTP which sides with the Afghan Taliban. ISKP also targets entities who side with them25. One such organization happens to be Jamiat Ulemae-Islam-Fazl (JUI-F), the religious party that organized the political rally in Bajaur. ISKP likely targeted them firstly because JUI-F supports the Taliban administration in Kabul, and secondly because it accepts democracy by partaking in elections, irrespective of its conservative and austere social worldview. JUI-F’s head, Fazlur Rehman, was part of the ruling coalition (PDM).

ISKP’s eventual lofty aspiration is to topple the government of Pakistan and its neighbors to bring into being a transnational caliphate. Its aim is overtly sectarian and global.

On August 14, 2023, Iran blamed ISKP armed militants for the second attack in less than a year on a major shrine in southern Shiraz, Fars province and arrested a group of foreign citizens for the attack. Ramezan Sharif, the spokesperson of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), said: “The goals of ISKP and affiliated terrorists are against the national interests and people of Iran”.26

A single gunman, identified as Rahmatollah Nowruzof, from Tajikistan, infiltrated the Shah Cherag Shrine and went on a shooting spree aimed at Shia pilgrims and staff, killing one and injuring numerous others. ISKP often mounts terror attacks against Iran from Tajikistan; Iran and Tajikistan have therefore cemented ties as they look warily at a terribly volatile Afghanistan.

ISKP indicts the Pakistani government and especially the Afghan Taliban for their non-Islamic rampant nationalism and faulted the Kabul administration’s dialogue with America (in Doha). ISKP also deepened its anti-China posture over the last few years, warning that it will target Beijing’s interests in Pakistan.27

With general elections forecast to take place towards either the end of the year or early in 202428, densely populated party-political rallies and electoral campaigning will remain a persistent target-base for radical extremists and a threat to Pakistan`s security forces. ISKP’s Bajaur bomb blast was not the first political rally related militant assault in Pakistan, nor was it the most lethally fatal.

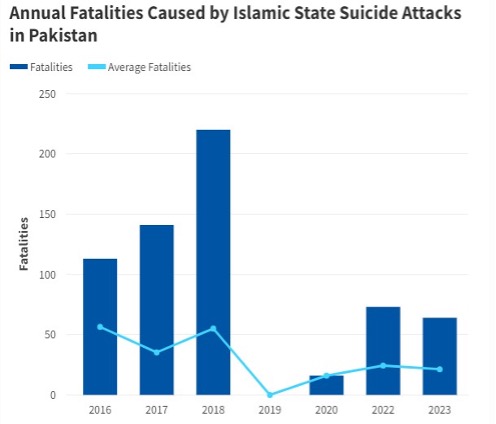

During the 2013 election campaign, there were over a hundred and nineteen attacks in the three weeks in the run up to election day. Islamabad has never delayed a general election due to extremist threats, including in those days. In 2018, ISKP claimed one of the most perniciously harmful bombings in Pakistani history, mercilessly killing 149 with 189 civilians severely wounded in Mastung district of Balochistan province29, as a suicide bomber detonated his explosives at an election rally of the Balochistan Awami Party (BAP) in the southwestern town of Drigarh, 35km south of the provincial capital, Quetta. Targeting highly crowded political rallies via suicide bombing from Mastung to Bajaur is now a signature ISKP terror trademark.

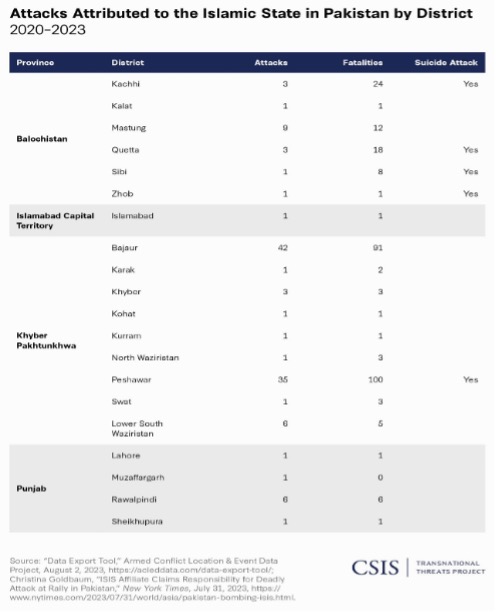

Since 2020 to date, view the soaring rise of ISKP perpetrated attacks intensifying everywhere in Pakistan, divided in detail by district.

ISKP’s activities in Balochistan are difficult to differentiate from those of the Islamic State Pakistan Province (ISPP), an independent network that formally parted ways with ISKP in May 2019 and that primarily mounts smaller-scale attacks.30 Such a myriad of parallel terror ecosystems and agendas in South Asia makes it harder for law enforcement agencies to constrain militants.

By allowing such extremists to fester on their soil, along with an inability to deal with ISKP in Afghanistan, the Afghan Taliban explicitly reneged on Part 1 of the Doha Agreement31 which offers assurances that the Taliban will not allow the use of Afghan soil by any multinational terrorist entity against the security of the United States and its allies including Pakistan. They also contravened part 3 of the Doha Declaration which detailed a political settlement resulting from an intraAfghan dialogue and negotiations between the Taliban and an inclusive negotiating team of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.

The aforementioned violations prove that the Afghan Taliban, despite lofty declaratory rhetoric, often go back on their word and that the government of Pakistan has to tread very cautiously while negotiating and dealing with them. This has widened the trust deficit between the already fragile Pakistan and Afghanistan relations, which, for the prosperous stability of South and Central Asia, must be bridged.

Trans-National Terror and why it is tougher to crack down on TTP and ISKP

The TTP has spearheaded some of the most fatal attacks within Pakistan since their inauspicious foundation in 2007. The TTP is an umbrella entity of numerous unsavoury hardline entities operating separately, and even individually in Pakistan. The fact that the TTP is atomized into distinct and multi-faceted organs, many of which have splintered from each other, renders it even more arduous for Pakistan`s authorities to pin-point and track them down, let alone sit on the negotiation table with them (no longer a safe or plausible option).

An example to prove that the TTP is not a unitary monolith but rather a confusing labyrinth (to the chagrin of law enforcement agents) was when, for instance, Khan Said, an adherent of a TTP commander who had formerly conflicted with Hakimullah32, mounted a rival leadership opposition bid against Baitullah Mehsud, a tribal head of the Mehsud tribe in South Waziristan33. Another example of internecine disagreements within the TTP was when disagreements were witnessed during the Zhob attack. Responsibility for the attacks was claimed by TJP, causing consternation within TTP rank and file regarding the accuracy of the claim.

Asad Afridi, who leads TTP in Dera Ismail Khan, openly defied the TJP’s claim and maintained that it was the TTP that conducted the attack. This posture, however, was rapidly renounced by TTP’s core spokesperson34, Mohammad Khorasani, who launched an opposing statement conceding the claim of TJP and labelling them “a brother organisation”.

Concomitantly, such divisions between Core Command and Dera Ismail Khan could highlight a cunning ruse whereby the proscribed TTP is using pseudonyms to escape rising pressure from the Afghan Taliban on them35. Asad Afridi’s assertion reportedly created humiliation for the TTP`s top brass, and in the aftermath of the alleged blunder, he was rapidly replaced.

Such divergence between Dera Ismail Khan and Central Command is more common within the TTP than observers believe. Such division and divergence attest to their homogeneity, just like ISKP’s terror in Balochistan is hard to differentiate from those of the Islamic StatePakistan Province (ISPP). Such ideological ambiguity between TTP and TJP as well as ISKP and ISPP makes it more challenging for Pakistani security forces to breach their already fragmented cells, intercept their covert (and often conflicting) communications and disrupt their violence extremism.

Furthermore, there have been defections and migrations away from TTP to ISKP (which explains the upsurge of terror by ISKP in Pakistan) as former ideologues bring their firebrand beliefs into more recently formed militant entities.

So disparate arteries of ISKP and TTP have commenced planning joint attacks together, with no clear reporting structure making it tougher for Pakistan`s agencies to intercept and penetrate such ever-changing terror cells. Rivalries, divided loyalties, rebranding36 and mergers make terror cells tougher to restrain. Several cells go purposely dormant (“sleeper cells” only to re-awaken when the heat is off them). Terror cells in constant flux, with ever-changing flexible circumstances and shifting loyalties imply that they are more fragmented, geographically dispersed with swift cross-border cross-province mobility, thereby gving them a competitive advantage.

These terror organizations are rarely ever unitary monoliths. The Afghan Taliban (though they do not show this in public) also have ideological rifts between the Haqqani and Akhundzada tribes37 as well as between Central Command in Kabul and the more stringent views espoused by Provincial Commanders.

Emir Akhundzada’s latest decree on cross-border Jihad.

After countless terrorist attacks against Pakistan in 2023, with Afghan bodies found at terror sites (Zhob) and hints from the Pakistan army that if such behaviour persists militants will be targeted by Pakistan within Afghanistan itself, the supreme leader of Afghanistan’s ruling Taliban, feeling the political heat, in early August 2023 officially labeled cross-border attacks, including those against Pakistan, as “haram”38 or forbidden under Islam.

High-ranking Taliban representatives articulated this “decree” from Emir Hibatullah Akhundzada to Pakistani officials during a recent bilateral dialogue to emphasize their resolve not to permit any outfit to threaten other states from Afghan territory. The topic appeared importantly during meetings between Asif Durrani, the special representative on Afghanistan, and his delegation (held in July) and Taliban’s Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi and Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani in Kabul.

The trip occurred amidst a surge in deadly attacks on Pakistani security forces and civilians, with the outlawed TTP claiming responsibility for planning most of the violence39. “Sheikh Hibatullah Akhundzada`s decrees bind every group pledging allegiance to him, and his decree is that attacking Pakistan is haram,”. The Pakistani delegation insisted that the Taliban make the decree public to stop/contain TTP and its Afghan backers from conducting terror activities that dampen and sour bilateral relations. The Taliban assured Pakistan that “We have circulated it among our people, among the [security] formations, and intelligence”.

Afghanistan`s national TV station broadcasted an audio speech by the Taliban Defense Minister, Muhammad Yaqoob, where he revealed some specifics regarding Hibatullah’s order on crossborder attacks. Yaqoob stated, refraining from naming any nation, that the Taliban supreme leader had ended the Jihad (holy war), and “obedience” to his decree is mandatory for all. “If someone still leaves Afghanistan intending to wage Jihad abroad, it cannot be considered Jihad anymore. If Mujahideen [Taliban forces] continue to fight despite orders from the emir to stop, it is not jihad but rather hostility,”40 Yaqoob stated.

Islamabad, however, remains deeply skeptical (and rightly so). Pakistan is aware of senior TTP miscreants, known to have pledged allegiance to Emir Hibatullah, and other militant bodies that have migrated their operational bases to Afghanistan41 ever since the Taliban resumed power in Kabul. The Taliban obstinately refute such allegations as unsubstantiated.

The Taliban counselled Islamabad to re-initiate negotiations with the TTP to reach a ‘negotiated settlement’. Pakistani officials understandably rejected the offer, rightfully asserting that former negotiations, brokered by Kabul in 2022 “miserably failed” as the TTP had repudiated any surrender of their arms and refused to pledge allegiance to the Constitution of Pakistan.

These are, and must be, Pakistan’s non-negotiable conditions. Whether the TTP like it or not, such demands must be complied with. Pakistan can ill-afford to let notorious Non-State Actors42 (NSAs) to dictate their terms and narratives (which include a release of their prisoners, less military presence in KPK and an implementation of their own distorted version of Shariah law).

Voice of America reported that the Taliban allegedly told the Pakistani delegation that they plan to move TTP members and families away from Afghanistan’s border regions to address Islamabad’s counterterrorism concerns. They also reiterated that Kabul requires financial assistance for relocating and resettling the extremists in other areas of Afghanistan.

The Afghan Taliban’s Troublesome Intransigence

The Afghan Taliban, while condemning the Bajaur blast, carries on denying Pakistani allegations. “After the recent security incident in Pakistan, officials have once again blamed Afghans instead of strengthening the security of their country,” stated Zabihullah Mujahid, chief spokesman for the Taliban administration. “The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan once again emphasizes that it is not in favour of any attack on Pakistan and we will not allow anyone to use the soil of Afghanistan against Pakistan. However, it is not our responsibility to prevent and control attacks inside the territory of Pakistan,” Mujahid added,43 asserting that “We do not allow them (TTP) to live and operate in Afghanistan. We have faced consequences of wars and do not want others to suffer like Afghanistan”. He, however conceded “This is a problem here, but it is also the responsibility of the other side (Pakistan) to find a solution”, asking Pakistan to substantiate its claims with proof.

However, in another interview with BBC Pashto, Mujahid adopted a more stringent stance, pleasing Afghan audiences, recommending Pakistan to straighten out “its internal issues itself, instead of pointing fingers at others”44. He continued “This is a naive approach to shift the blame of one’s own failures to others,” and warned of a “serious reaction if Pakistan used force inside Afghanistan”. He snubbed the Pakistani government’s petition of the Doha accord, saying that it was signed between the Taliban and the US, not Pakistan.

However, the Doha Accord makes reference to “Afghanistan`s neighbours and the region” which most clearly alludes to Pakistan. The Islamic Emirate’s Orwellian ‘doublespeak’45 on the issue is astonishing, given how Pakistan is efficiently acting as a bridge between the Kabul regime and the international community, at present.

The war of words accentuates the swiftly waning bilateral rapport between the two states, as Pakistan endures mounting assaults on its law enforcement officers and citizens alike. The Afghan Taliban persist in reminding the global community that the Doha Peace Accord did not include issues related to Pakistan46, and they keep portraying TTP challenges as Pakistan’s own domestic internal matter. If Kabul keeps negating its responsibilities, bilateral relations will slide further downhill.

The TTP remains theologically, spiritually and conceptually affiliated with the Afghan Taliban but operates distinctly. Among their manifold demands, the TTP want the emancipation and setting free of their associates in Pakistan’s custody47, and a diminished Pakistani military presence in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

Pakistan, in turn, demands that the TTP renounce all arms and pledge allegiance to Pakistan`s constitution. Neither of which have been done.

Luring the Afghan Taliban through Regional Economic Connectivity

There are alternative carrots and sticks in Islamabad`s policy portfolio that must be cautiously contemplated with the aspiration to both positively influence Taliban leadership as well as elevate the cost of non-compliance for Kabul.

A “carrot” in Islamabad’s armoury is to lure the Afghan Taliban through regional economic connectivity megaprojects. One such positive stride was accomplished as railway representatives from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Uzbekistan in July 2023 established the route of a tri-nation railway linkage aspiring to intensify regional, transit, and trilateral commerce amongst the cooperating states.

The Joint Working Group (JWG) of the railway venture concluded the joint procedures with relevant railways/transport ministries. The key purpose of the tri-nation project is to establish a regional railway connectivity route linking Uzbekistan Railways with Pakistan Railways through Afghanistan. The connectivity will traverse the journey from Termez to Mazar-e-Sharif, Logar and Karachi. A major plus point of this 573 km railway project48 is that this trans-railway link will offer linkages from Russia, Uzbekistan through to Pakistan and onto the Arabian Gulf.

The Uzbekistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan (UAP)49 railway project, for passengers as well as landed freight facilities, won’t only deepen regional, economic transit, and trilateral commerce, but will intensify people-to-people regional connectivity.

The participants consented to a joint direction for technical issues, project financing opportunities and other essential facets for a smooth execution of the project. Though the materialization of the project will require major funding from large donors such as the Asian Development Bank, luring the Taliban with uplifting regional prosperity projects like this has the promise and potential to make the Afghan Taliban realize that bad blood between neighbours favours no one and puts too much at stake. Such initiatives are key to tame trans-national terrorism risks.

Border Management Policies and Beyond

Pakistan’s wisest course of action over the near-term is to fully seal and fortify border security, but contemporary endeavours encountered challenges.50 For instance, in December 2022 and in February 2023 Afghan border security guards breached Pakistan’s side of the border. Specifically, Torkham, the major border crossing between Afghanistan and Pakistan, where local residents reported gunshots close to the usually bustling border transit point. Militants belonging to TTP, Jamaat-ulAhrar and now ISKP also use the Af-Pak border in Spin Boldak to spread terror.

The border fencing was about ninety-four per cent complete as of 5 January 2022, when Pakistan`s Interior Minister confirmed that twenty km remains to be fenced in totality51. As of April 2023, 98% of fencing and 85% of fortification have been completed. The project is estimated to cost close to $532 million. Despite financial challenges, the time is ripe for Pakistan to fully seal and fortify the border. Nothing is more sacred than the safety of our citizens.

The Durand Line, which was established as a bilateral border by the British is a perennial bitter bone of contention between Afghanistan and Pakistan since decades. Pakistan has tried to make Afghanistan accept this as an international border, yet Afghanistan has not and will not accept it, primarily due to Pakhtun tribal codes and allegiances which transcend borders.

Till the acceptance of the Durand line as a formal border is not accepted, cross-border smuggling, narcotics, arms trafficking, internally displaced persons (IDP`s) and militant cross-over will persist. One workable solution regarding the border could be to form a Jirga based along the traditional Pakhtunwali code to resolve the border and militant issues. The composition of the Jirga must be broad-based, inclusive, and its decision binding52.

In addition to our Federal Investigation Agency`s (FIA) Integrated Border Management System (IBMS) tech and intel, Pakistan, no doubt, must conduct a more efficient supervision of its border management as there are credible reports of militants snaking their way into Pakistan amongst the routine daily visitors from authorized crossing points like Torkham and Chaman.

One innovative approach toward better border management policy in Pakistan was interestingly initiated in Austria. Top-brass at Pakistan’s Federal Investigation Agency (FIA), with the backing of the Ministry of Interior of Austria, are collaborating to develop a border management leadership training programme for the senior managers responsible for immigration control at the 32 Border Crossing Points (BCPs) on Pakistan’s borders.

This is a truly innovative program of its kind in Pakistan and can prove invaluable to FIA`s senior managers in charge of immigration controls at Pakistan’s BCPs. Conducted throughout 2022, the leadership programme succeeded in equipping the FIA with a cadre of internal “master” trainers via a substantive training initiative, developing a customized training curriculum, and training over 40 FIA managers stationed at Islamabad, Lahore, Multan, Peshawar and Karachi airports, as well as FIA regional offices and land BCPs with Afghanistan and Iran53.

Pakistan’s goodwill gestures and bridge-building

Asif Ali Khan Durrani, Pakistan`s special representative to Afghanistan, unequivocally demanded the Afghan government to give up TTP top brass to Pakistan, in order for them to be brought to justice for their crimes against humanity. “This is our demand… the TTP leaders should be neutralised so they do not pose any threat to Pakistan. They should not use Afghan soil against Pakistan,”54 Mr. Durrani said. He specifically dismissed further negotiations with the TTP, affirming that Islamabad had exhausted that alternative which did not yield any affirmative outcomes.

Pakistan’s military, defence and foreign ministry have now all dispatched stern messages to Kabul, that if TTP terrorism persists, Islamabad will do what is necessary to keep its citizens safe and that reprisal can be on any level.

Islamabad stands vindicated in its demands. Ever since the fall of Kabul in August 2021, Islamabad has been the most vociferous supporter of the Afghan issue, with former Foreign Minister, Bilawal BhuttoZardari, consistently urging multiple stakeholders in the international community to engage with the Islamic Emirate, for the sake of the Afghans55, if nothing else.

Stakeholders in the Kabul administration insisted that they were initiating procedures to curb TTP`s violent extremists, contending that entities such as TTP often operate from the rugged mountainous terrain of eastern Afghanistan in Paktika, Paktia, Khost and Kunar, territory areas where, purportedly, the Islamic Emirate’s writ doesn’t apply56.

While the West has been yearning to boycott the Taliban administration over their glaring infringement of human rights, particularly the prohibition on girls’ education and working women57, Pakistan has been beseeching the international community to resolve the matters through ‘engagement’ rather than ‘alienation’.

Pakistan is also a strategic partner for Afghanistan’s languishing economy, with a majority of the state’s trade and a huge chunk of its food and aid supplies being routed through Pakistan.

Skeptics reason that it is increasingly tougher to view Af-Pak relations cementing over the near to mid-term, for they persist in a perennial finger-pointing blame game. At best, both states can aspire to “manage” relations, but not much beyond that should be expected.

Those informed of the ground-realities assert that TTP militants do not seek safe havens, as was formerly the reality under the Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani governments. At present, these terrorists live openly and operate freely in the main cities of Afghanistan.

KP and Baluchistan provinces bore the brunt of most attacks. The TTP and the so-called Baluch Liberation Army, both classified as international terrorist organizations, have taken responsibility for most of the bloodshed in the two provinces and elsewhere in Pakistan58. Balochistan remains geo-strategically significant due to its abundance of energy and minerals reserves and is where a low-level insurgency has raged for years.

The recent spate of attacks (especially in Bajaur) will only further aggravate already simmering strains between both countries59. Pakistan was overly optimistic in hoping that the Afghan administration would clamp down on the TTP, in this regard Kabul evidently neither acted resolutely nor conclusively.

Meanwhile ISKP carries on clinching traction, terrain, influence and presence in Pakistan’s tribal border regions. Pakistan’s exasperation with the Taliban has incrementally risen60, irrespective of whether the TTP is considered as inactive or restrained. Poignant messages were conveyed to Kabul by Pakistan`s Corps Commanders Conference in July which echoes a grave disenchantment within the top brass over Afghanistan’s ostensible reluctance to stem the tide of extremists and weaponry coursing through Pakistan’s western border.

Former foreign minister, Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari’s speeches reflect Pakistan communicating its vexation more emphatically, with the hope of influencing the Taliban to heed its admonition more cautiously.

A senior delegation headed by former Defence Minister Khawaja Asif visited Kabul for talks in February. After the recent attacks against Pakistan Mr. Asif sternly stated, “Afghanistan is neither fulfilling its obligations as a neighbouring country nor safeguarding the Doha agreement”. He said, “terrorists who shed the blood of Pakistanis find refuge on Afghan soil”, and warned that “Pakistan would employ all possible resources and measures”61 in response. After Zabiullah`s intransigence on the matter, Khawaja Asif persisted with, “Pakistan stands resolute in uprooting terrorism from its soil, whatever the source… regardless of whether or not Kabul has the will to reign in militants from within its borders”.

Pakistan’s February delegation intensely emphasized that the Afghan Taliban must comprehend Pakistan’s non-negotiable stance on terror, especially emanating from Afghan territory and ensure a rocksolid commitment from Kabul to stifle and restrain TTP and deny it safe havens.62 In these talks, senior-ranking Taliban officials requested financial aid, as they say they are cash-strapped since the U.S froze billions of Afghan central bank reserves. Kabul told Islamabad that they would use that financial assistance to neutralize, disarm and resettle (away from the border with Pakistan) TTP combatants and their families, projected to be between five to six thousand in number. Yet all this was to no avail.

Afghanistan’s Foreign Minister, Amir Khan Muttaqi, visited Islamabad in May and also met the Army chief63. Yet the dialogue had minimal effect and could not curb the bloodletting, with the TTP conducting more than ninety attacks solely in the month of July 2023. The TTP represents a unique dilemma for the Afghan Taliban owing to the entities` historical allegiance, shared background and common cultural roots.

Pakistan is diplomatically re-engaging with America to counter regional security trials and tribulations. General Michael Erik Kurilla64, heading the United States Central Command, spoke to Pakistan’s army chief in July 2023 during his second visit to Pakistan in six months. Both stakeholders spoke on matters related to regional security and defence collaboration. The U.S. can no longer treat TTP and ISKP as “localized” threats. History attests as to how terror organizations tend to infectiously spread, grow and contaminate extremist minds, transcending borders and boundaries, taking a true trans-national footing.

ISKP wormed their way into South Asia, being an offshoot of ISIS Syria and Iraq. Witness the growing number of Wilayats (territorial claims) made by the self-styled Islamic State (IS) to further their agenda of erecting a global caliphate. Al-Qaeda in the Indian Sub-Continent (AQIS) also amply illustrates the crossborder and highly mobile nature of global terror. Such organizations remain strategically positioned in weak ungoverned regions of countries where “governance vacuums exist” and the government lacks substantial clout and control.

For the unforeseeable future, TTP will keep unleashing terror and turbulence in Pakistan`s tribal belt and all the aforementioned dialogue and meetings have not yet yielded the desired outcomes.

Islamabad can carry on issuing Kabul with public warnings and ultimatums and hope that this will force the Taliban to capitulate and comply. Yet this tried-and-tested formula hasn’t worked thus far and cannot produce a distinct result from the past.

Should Pakistan do what Afghan Taliban leaders often desire and partake in talks with the TTP once more?65 That was an unmitigated disaster on a previous occasion and the blowback was devastating for Pakistan, the ramifications of which it is still having to tackle.

Dialogue irreparably failed when it became crystal-clear that the TTP’s unreasonable demands were non-negotiable.

Such demands included the removal of Pakistan’s military corps from the border area (a grave security faux-pas), to undo FATA’s merger with KP which would contravene Pakistan`s 25th Amendment after which FATA was officially merged with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa66. The TTP also sought to force the imposition of it`s own brand of Shariah law in some KP regions. Given such unrealistic demands, Pakistan’s military officials have understandably rejected dialogue with TTP.

Should Pakistan envisage targeted strikes against militant sanctuaries in Afghanistan if the Taliban persistently decline to act against TTP? Covert kinetic strikes have hitherto been launched by Pakistan, aimed at TTP67. Such strikes took out some of their senior cadre. Yet this is not a sustainable measure over the long-haul and carries with it blatant risks of irreversible escalation.

A Regional Solution

The deficit of a political consensus in the country at a crucial juncture remains Islamabad`s most significant drawback. Political polarisation has rendered it close to impossible for the country`s security establishment to forge a national approach on countering terrorism. The lack of effective governance has generated broad-based disillusionment68, particularly with younger citizens, making them gravitate towards radical ideologies and methods.

To make a bad situation worse, the political elite have no clear sense of direction, vision and getting the country back on course. Internationally, the interest in Pakistan is ebbing, further salting the wounds of a crisisladen country that must get a grip. With the upcoming national elections the security situation is likelier to disintegrate as extremists exploit rallies and huge gatherings, making for easy prey.

Islamabad, as stated earlier, must work on a regional solution. This could evolve a coordinated multilateral regional strategy so that combined pressure is applied on Kabul with stringent deliverables and deadlines. This could also involve organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the OIC, the Greater Eurasian Partnership and their respective counter-terror wings. Security and counterterrorism, after all, remains a worry for all of Afghanistan’s neighbours even though their self-interests may diverge.

Dealing decisively with the TTP and related terrorists necessitates a multi-pronged approach that addresses the root causes of the group’s violence along with the underlying issues leading to its resurgence after the Afghan Taliban’s takeover. Some measures must include “soft strategies” such as disengagement and deradicalization campaigns, peace education69, amnesty programs (within reasonableness) for militants who surrender themselves and placing them in newly formed deradicalization and rehabilitation centers. Empowering civil society to counter violent extremism through anonymous web complaint and citizen type apps and portals can also be a way forward.

What is evident is that Pakistan’s current Afghan foreign policy must be re-thought, revised and reset to more successfully safeguard its security and self-interests.

References

- Ahmet Yiğitalp Tulga (2021) Hard and Soft Terrorism Concepts: The Case of ISIS. Journal of terrorism research, Volume 3, Issue 2, July-December, 2021. A National Counter Terrorism Authority Pakistan (NACTA) Journal.

- Relief Web (2023) Pakistan crisis response plan, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), 18 January, 2023.

- Khan, A. Iftikhar, (2023) Terror attacks increased in Pakistan after Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, Dawn, 1 June, 2023.

- Pakistan Institute for Peace Studies (PIPS) (2023) “Pakistan`s Afghan perspective and policy options”, June 6, 2023. PIPS is an Islamabad based think-tank.

- Ibid,.

- Muhammad Khurasani (2023) “Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan explanation about the Peshawar Police Lines mosque attack,” Umar Media, January 31, 2023

- Adil, Jawad (2023) Taliban claim attack on police in Pakistan`s Karachi, 7 dead, Associated Press, February 18, 2023.

- Al Jazeera (2023) Suspected IED attack kills 11 labourers in Pakistan`s North Waziristan, August 20, 2023.

- Sayed, Abdul and Hamming, Tore (2023) The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan after the Taliban`s Afghanistan takeover, Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, Volume 16, Issue 5, May 2023.

- Ibid,.

- Sayed, Abdul and Hamming, Refslund Tore (2023) The growing threat of the Islamic State in Afghanistan and South Asia, Special Report by the United States Institute of Peace, Number 520, June 2023.

- Ahmed, Samina (2023) The Pakistani Taliban test ties between Islamabad and Kabul, International Crisis Group, 29 March, 2023.

- Gul, Ayaz (2023) Militants raid Pakistan army base: 12 soldiers, Civilian die in clashes, Voice of America, July 12, 2023.

- Gul, Ayaz (2023) Afghan Taliban chief deems cross-border attacks on Pakistan forbidden, Voice of America, August 6, 2023.

- Pakistani army chief warns Afghan Taliban against harbouring militants (2023) Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty`s Radio Mashaal, July 15, 2023.

- Kaura, Vinay (2022) Pakistan-Afghan Taliban relations face mounting challenges, Middle East Institute, 2 December, 2022.

- UNSC, “Twenty-Second Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team.”

- Gul, Ayaz (2023) Afghan Taliban chief deems cross-border attacks on Pakistan forbidden, Voice of America, August 6, 2023

- Akbar, Naveed (2023) Security forces kill five terrorists in Zhob Garrison clearance ops, Aaj News English, 12 July, 2023.

- Afghanistan`s security challenges under the Taliban (2022) International Crisis Group, Report 326, Asia, August 12, 2022.

- Tyson, Kathryn (2022) Islamic State increases attacks as Pakistani Taliban negotiates, Critical threats project at the American Enterprise Institute, November 21, 2022.

- This researcher gained the figure of 241 million and rising from Worldometer (2023) The population of Pakistan, as per United Nations

- Nodirbek Soliev (2021) “The April 2020 Islamic State Terror Plot against U.S. and NATO Military Bases in Germany: The Tajik Connection,” CTC Sentinel 14, no. 1, January 2021.

- Lamothe, Dan and Warrick, Joby (2023) “Afghanistan Has Become a Terrorism Staging Ground Again, Leak Reveals,” Washington Post, April 22, 2023

- Nasar, Najeeb Ullah (2018) ISKP`s objectives in Afghanistan, Center for Strategic and Contemporary Research, February 14, 2018.

- Bayramli, Nigar (2023) Iran vows decisive response to terrorists over Shrine attack, Caspian News, August 15, 2023.

- Gul, Ayaz (2023) Afghan Taliban chief deems cross-border attacks on Pakistan forbidden, Voice of America, August 6, 2023.

- Economist Intelligence Unit (2023) Pakistan election: limited solution to political dysfunction, June 14, 2023.

- Abbas, Hassan (2021) Extremism and terrorism trends in Pakistan: changing dynamics and new challenges, Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, Volume 14, Issue 2, February, 2021.

- Schulz, Dante (2022) ISKP`s propaganda threatens Asia`s security apparatus, Stimson Center, October 4, 2022.

- The purpose of the 2020 Doha Agreement was to grant the Afghan Taliban international legitimacy, address the qualms of regional neighbours in South and Central Asia, detail the American withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan all being dependent on the Taliban`s rock-solid guarantees and assurances that Afghan soil would not be utilized as a launch pad by the TTP, al-Qaeda or Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP), for attacks vis-à-vis the United States, Pakistan or any regional neighbours. For more consult: The Doha Agreement (2020) An Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan, signed in Doha, Qatar on February 29, 2020 between the U.S. Department of State and the Afghanistan Taliban.

- TTP`s presence in South Asia (2023) National Counter-terrorism Center, Directorate of National Intelligence.

- TTP`s presence in South Asia (2023) National Counter-terrorism Center, Directorate of National Intelligence.

- Firdous, Iftikhar and Valle, Ricardo (2023) The perplexing credit taking dynamics within militant organizations, The Khorasan Diary, July 13, 2023.

- Mir, Asfandyar (2022) Pakistan`s twin Taliban problem, United States Institute of Peace, 4 May, 2022.

- Jadoon, Amira, Jahabani, Nakissa and Charmaine Willis (2018) “Challenging the ISK Brand in Afghanistan-Pakistan: Rivalries and Divided Loyalties,” CTC Sentinel, Volume 11, Issue 4, April 2018.

- The Haqqani network (2021) The new kingmakers in Kabul, War on the rocks, November 12, 2023.

- Gul, Ayaz (2023) Afghan Taliban chief deems cross-border attacks on Pakistan forbidden, Voice of America, August 6, 2023.

- Ibid,.

- Ibid,.

- Mir, Asfandyar (2022) Pakistan`s twin Taliban problem, United States Institute of Peace, 4 May, 2022.

- Felbab-Brown, Vanda (2023) Nonstate armed actors in 2023: persistence amid geopolitical shuffles, Brookings, Jan 27, 2023. Twitter: @VFelbabBrown

- Pakistan bombing puts focus on it`s struggle to keep militants at bay (2023) Arab News, 31 July, 2023.

- Ibid,.

- Orwell, G. (2021). Nineteen Eighty-Four. Penguin Classics.

- Kumar, Rahul (2023) Afghanistan, Pakistan relations slide downhill over TTP terror, India Narrative, Jul 18, 2023.

- Ahmed, Munir (2023) What`s behind the Pakistani Taliban`s insurgency? Associated Press, Jan 30, 2023.

- Latif, Aamir (2023) Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan sign tri-partite railway link project, Anadolu Ajansi, 18 July, 2023.

- Noor, Asif, Muhammad (2023) Uzbekistan-Afghanistan Pakistan Railway Network- Fostering Regional Connectivity, Gwadar Pro, July 22, 2023.

- Basit, Abdul (2021) Pakistan Afghanistan border fence, a step in the right direction, Al Jazeera, 25 February, 2021.

- Yousaf, Kamran (2022) Pak-Afghan border fencing here to stay: DG ISPR, Express Tribune, January 5, 2022.

- Khalid, Ozer (2023) The resurgence of TTP and Pakistan`s counter-terrorism plight, Criterion Quarterly, April, 2023.

- International Center for Migration Policy Development (2023) Austrian support leads to stronger leadership at Pakistan`s borders, ICMPD Budapest Process, May 11, 2023.

- Shabbir, Saima (2023) Pakistani envoy meets Afghan Taliban leaders in Kabul, Arab News, July 21, 2023.

- Latif, Aamir (2023) Pakistan offers assistance to Afghanistan to ‘curb terrorism’, Anadolu Ajansi, Aug 1, 2023.

- Sayed, Abdul and Hamming, Tore (2023) The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan after the Taliban`s Afghanistan takeover, Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, Volume 16, Issue 5, May 2023.

- Fetrat, Sahar (2023) One year on, the Taliban still attacking girls` right to education, Human Rights Watch, Mar 24, 2023. Twitter: @Sahar_fetrat

- Gul, Ayaz (2023) Militants raid Pakistan army base: 12 soldiers, Civilian die in clashes, Voice of America, July 12, 2023.

- Hussain, Abid (2021) Violence surges in Pakistan`s tribal belt as Taliban, IS-K go on attack, British Broadcasting Corporation, October 13, 2021.

- Mir, Asfandyar (2022) Pakistan`s twin Taliban problem, United States Institute of Peace, 4 May, 2022.

- Hussain, Abid (2023) Pakistan`s defence and spy chiefs discuss security with Taliban, Al Jazeera, Feb 22, 2023.

- Gul, Imtiaz (2023) Explaining the resurgence of terrorist violence in Pakistan. Center for research and security studies. 29 March, 2023. Twitter: @ImtiazGul60

- Mehmood, Khalid (2023) Muttaqi makes Pakistan, TTP talks pitch, Express Tribune, May 8, 2023.

- Readout: General Kurilla visits Pakistan Armed Forces (2023) Press Release Number 20230725-01 by the S Central Command, July 25, 2023.

- Yousaf, Kamran (2023) Islamabad to convey strong message to Kabul on TTP, Express Tribune, July 18, 2023.

- Which received assent from President Mamnoon Hussain on 31 May 2018.

- Ahmed, Samina (2023) The Pakistani Taliban test ties between Islamabad and Kabul, International Crisis Group, 29 March, 2023.

- Shuja Nawaz et al. (2023) The unfinished efforts against terrorism and militancy in Pakistan, Atlantic Council, March 31, 2023.

- Qadeem, Mossarat (2021) Peace Education: A Remedy for Preventing Violent Extremism in Pakistan, Journal of terrorism research, Volume 3, Issue 2, JulyDecember, 2021. A National Counter Terrorism Authority Pakistan (NACTA) Journal.