Geneses, Perceptions, Challenges and the Way Forward

by Air Commodore (R) Khalid Iqbal TI (M)*

The writer is a retired air commodore of Pakistan Air Force, he is founding chairperson of a leading think tank “Pakistan Focus”. An abridged version of this paper was read in an international conference organized by the Political Science Department of Peshawar University (Bara Gali Campus) and HSF Islamabad on September 3-5 2018. The paper has since been updated, research closed on July 22, 2019.

Abstract

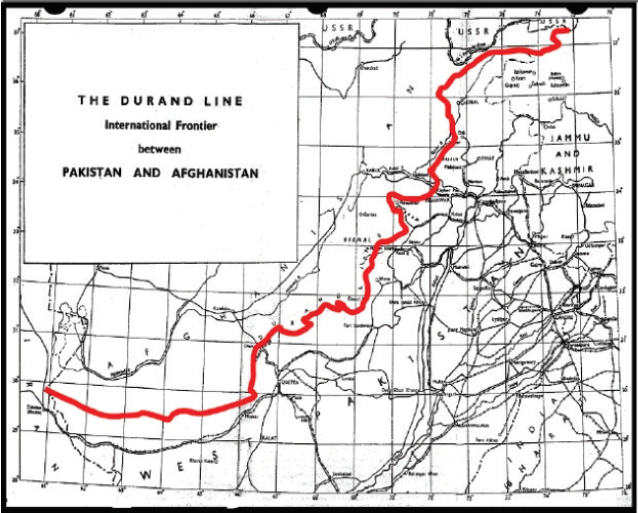

(The land mass constituting Pakistan-Afghanistan borderlands changed hands between British India and the Afghan government, at times more than once. 1 The current status of these borderlands is often traced back to the Durand Line Agreement 1893 2 that was, by and large, upheld by all Afghan governments until Pakistan came into being. International community recognizes The Durand Line as an international border 3, since 1947. Afghanistan does not. People living astride the Durand Line think that it never existed. The Durand Line Agreement, a fairly straight forward single page, seven articles exchange of territories document, has, over time, gathered a huge baggage of myths, thus throwing up a functionally complex borderland in the socio-political context, presenting a governance nightmare. The current borderland status draws its strength from the benefits thrown up by informal trade and illicit trafficking that underwrites a huge informal borderland economy. Pakistan is struggling to mainstream its side of the borderland through legislative, political and administrative measures. Due to continuing political turmoil in Afghanistan, the well-being of its side of the borderland has, since long, been neglected. Notwithstanding the zeal for mainstreaming by one side and indifference by the other side, the life style of the people astride the international border bears amazing resemblance – archival texts suggest – as if the clock froze centuries ago. Culturally this trans-border region is so comprehensively integrated that one wonders whether air-tight separation between the conjoint twins is a viable option. The land mark 31st constitutional amendment marks the notional integration of Borderlands with KP 4, but substantive integration is still a far cry, warranting bold steps at local, bilateral (i.e. Pakistan-Afghanistan) and international levels. There is need to evolve major enablers and structure requisite hasteners for making this integration successful, leading to an adequate and equitable trickle down of sustainable empowerment to grass root levels and ensuring wellbeing and prosperity of the people living astride the Durand Line.

Alongside historic review of events leading to the current situation, this paper examines the ways and means of speedy integration of tribal areas into mainland Pakistan. – Author)

Background

Frequent stampeding by advancing and retreating militaries induced a perpetual sense of insecurity leading to a culture of arms bearing as a matter of routine, and using them on the slightest pretext. Thus making the Pak-Afghan borderland a strategic tinderbox. Readily available drug making materials in Afghanistan and generously rewarding drug markets in Europe and Americas fascinated those living in the borderland to make quick financial gains by evolving and safeguarding international trafficking lanes. A frequent influx of refugees has had positive and negative ramifications for both countries, as indeed the region. The myth of an independent tribal belt is misleading as, in reality, the presence of the draconian Federal Crimes Regulation (FCR) 1901 5, has been harsh and oppressive. The concept of collective punishment, perforce, tied each individual to his tribe 6, and one could not afford to think of any other institution worthy of primary loyalty. Contrary to the myth of isolation, the residents of the area are well travelled and well connected. Acquisition and distribution of wealth is neither uniform nor equitable. Elementary Human Resource Development Indicators are lower than even the poorest countries of the World 7.

Successive governments in Pakistan have been taking tangible steps for mainstreaming its side of the borderlands in a block building approach. The draconian FCR was amended in 2011 8 and then done away with; political parties were made functional and universal franchise implemented 9; superior courts were given jurisdiction over these borderlands 10; and, finally, through a comprehensive 31st constitutional amendment, tribal areas have been regrouped to their ethno-cultural conjoins 11.

Pakistan-Afghanistan borderland management presents a unique political mosaic; its collective and cooperative mainstreaming is a far cry. Viability of steps taken by Pakistan will remain questionable unless there are matching measures by the Afghan government on their side of the borderlands.

The major causes leading to the current situation are:

(a) Interpretations and misinterpretations of the Durand Line Agreement

(b) Socio-political challenges of a borderline dividing households and families

(c) Huge gap between formal and informal trade

(d) Location at cross roads of human, arms and drug trafficking routes

(e) Post 9/11 terrorism and counter terrorism dilemmas

(f) Regional and global dynamics of neo-Great Game

Durand Line Agreement November 12, 1893: Myth and Realities

The Durand Line Agreement is a single page document containing seven articles pertaining to the exchange of territories between Afghanistan and British India governments, and laying down the principles of border and borderland management.

The Durand Line Agreement 12 is the most misunderstood agreement by the people of the two countries residing across the line; the main reason is that its context and text is often misquoted and misinterpreted by the Afghan government.

The signing of Durand Line Agreement and subsequent demarcation of borders brought a sense of stability in bilateral relations and set a tempo and tenor for a number of subsequent agreements between the two sides. All such agreements acknowledged and re-affirmed the validity of the Durand Line Agreement. Realising the end of the British Raj and emergence of Pakistan, Afghan foreign minister despatched a communique to Indian Prime Minister Jawahar Laal Nehru in 1946. The letter acknowledged the legality of the Durand Line Agreement with British India, and tried to build a narrative for creating confusion about continuation of this Agreement with the upcoming new state – Pakistan 13. The Prime Minister of British India ridiculed the Afghan government by stating: “if one was to go by historic perspective then once the Hindu Kush range marked the Afghan border with India” 14. All Afghan governments, except one odd aberration, had recognized the Durand Line as a legitimate international border till 1947. Since then, all Afghan governments have preferred to repudiate it 15.

Historic Position

Two myths which the Afghan side often likes to put forward are: the “signing of Durand Line Agreement under duress”; and “a 100 years’ time bar” on this agreement. Afghan historic interpretations have deep roots and are full of pot holes. Some Afghan ultra-nationalists continue to see Peshawar as Afghanistan’s old winter capital snatched from them by the Sikhs in 1834 16. Most of the maps of Pakistan published by them begin Pakistani territories from the borders of Punjab – East of the Indus. In practice, successive Afghan governments endorsed the validity of the Durand Line agreement by signing subsequent accords with the British Empire based on this Agreement— in 1905, 1919, 1921 and 1930 17. The contention that “Amir signed Durand Line Agreement under coercion” is also negated by overwhelming evidence. It was challenged by the Amir himself as well as all the documented narrative of the Darbar (Royal court) held by the Amir for approval of the Agreement by the Jirga. And as regards 100 years’ time limit, no authentic reference has been put forward to support the impression.

“Amir Abdur Rehman was generally satisfied with the outcome of his negotiations with Sir Mortimer Durand. They were conducted according to the satisfaction of both parties, and eliminated past misunderstandings between the two. While signing the Agreement, the Amir held a ‘durbar’ where his two elder sons, high-ranking civil and military officers, and four hundred leading chiefs were present. Writing about this occasion, Sir Mortimer states, ‘He (Amir) made a really first class speech beginning. He then urged his people to be true friends to us and to make their children the same. He said that we did them nothing but good and had no designs on their country. After each period of his speech, there were shouts of ‘Approved! Approved’’ from amongst those present. This account has been corroborated by the Amir himself in his memoirs where he writes that “before the audience I made a speech to commence the proceedings in which I gave an outline of all the understanding which had been agreed upon and the provisions which had been signed for the information of my nation and my people and all those who were present. I praised God for bringing about friendly relations which now existed between the two Governments and putting them on a closer footing than they had been before 18.”

Such accounts, along with the nature and terms of the Durand Line Agreement, adequately indicate that the agreement was not forced on the Afghan side and that this action had requisite institutionalized public consent 19. Following the “third Anglo-Afghan War”, both sides concluded the “Rawalpindi Treaty” in 1919. Subsequently, “the Anglo-Afghan Treaty of 1921” was signed. In both these treaties, the two sides reaffirmed the validity of the Durand Line Agreement 20. Ever since, the international community has recognized the legitimacy of the Durand Line: initially as the international border between the Raj and Afghanistan, and later between Pakistan and Afghanistan 21.

The second misinterpretation of the Durand Line Agreement is that after 100 years, the territory given up by Kabul would be returned to it 22. In the past, Afghan governments had been claiming, again without admissible legal evidence, that the “Dari and Pashto language copies of the Durand Line agreement have specifically mentioned the 100 years period, but it was left out from the English version by Mortimer Durand” 23, who insisted that only the English text would be the authentic text of the Durand Line Agreement; and he signed only the English document. The Afghan government is yet to produce supporting evidence to validate its claim 24. In addition, Afghanistan has abstained from taking this matter to any international forum due to their inherently weak legal standing.

Another subject is about “easement rights granted to the tribes living close to the border and affected by some of the restrictions placed on their movement across the Pak-Afghan border”. While there is no mention of “easement rights”, traditionally the people separated by the Durand Line “have enjoyed free movement across the Pak-Afghan border by simply producing a ‘rahdari’ (permit) issued to them for identification purposes 25. These easement rights are limited to only Shinwari and Waziri tribes; and are quite limited in scope and extent, they can travel up to 20 kilometres across the Durand Line for attending social functions, such as deaths, weddings, etc, of relatives” 26. The problem arises when those residing in, for instance, Mazar-e- Sharif in the north and Karachi in the south, start claiming easement rights.

On its independence on August 14, 1947, Pakistan succeeded to “all the international rights and obligations of the British Indian Government with the Afghan government; for which it assumed responsibility in line with Article 62 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. 27

Positions and Perspectives

Pakistan’s interest “with regard to the border is to maintain the status quo” 28. Whereas Afghanistan’s intent is unclear; and it lacks consistency. Numerous actions of the Afghan state have sent across signals of not only de facto but even de jure recognition of the border. Afghan governments are politically weak; hence fearful that internal political opponents would portray any negotiated settlement with Pakistan as a national betrayal. The saga of Afghanistan’s borders with all its neighbours presents the same story of divided communities. Afghanistan sparingly regulates any of its international borders. Mostly, the other sides “feel compelled” to manage their respective sides.

For the people who live along the Durand Line, it has never constituted an international border. They act as if it does not exist. Local inhabitants prefer to see the border issue remain unresolved because it makes it easier for them to reject state authority of all types and benefit from illicit trade, trafficking and peddling.

The International Community has always recognised the Durand Line as an international border. And through its actions in the ‘Global War on Terror,’ it has reaffirmed the recognition of the Durand Line as the de jure international border. International Security Assistance Forces (ISAF) and NATO land forces never crossed the Durand Line, even in hot pursuit operations. The US and the UK have always recognized the Durand Line as an international border.

Areas of Concern: Governance and Societal issues

Salman Bangash in his article “Areas of concern: Problems with the Fata merger” argues that due to “a peculiar form of administrative structure in the tribal areas, the inhabitants of these areas were subjected to systematic exploitation and unfair treatment. The subordination of the populace was implemented through military operations, intimidation, bribery and the divide and rule policy”. Tribal administration was run under the FCR, a law often referred to as an “engine of oppression and subjugation” 29. The system continued for decades after independence. FATA’s merger with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is a significant step in its own right; however, its implementation would be a Herculean task.

Major challenges include restructuring of tribal administrative structures and systems, and rewriting the role, responsibilities and rules of the functioning of various categories of officials, and a whole range of tribal forces like: the Frontier Corps; Frontier Constabulary; the Levies Force; Khasadars, etc 30. It is also still unresolved as to what type of model shall be adopted for setting up the various government functionaries in the ex-tribal areas, like the recruitment of the lower judiciary and setting up of police stations 31. Indications are that the system prevalent in KP would be extended to erstwhile FATA/PATA entities, which have already assumed the role of districts; and the Political Agents have been re-designated as Deputy Commissioners. The advantage of this approach is that the entire KP would have a uniform governance pattern.

Matters related to rehabilitation, reorganisation and reconstruction have been adversely impacted by militancy and military operations. Societal structures stand shattered. Multi-dimensional polarization and upheavals “have not only fragmented and shattered the tribal structures; they have also generated and ignited ill feelings and grievances among certain segments of the populace towards the state of Pakistan” 32.

The new setup needs to extend a healing touch through reconciliation. There is need to defuse and placate the mind-set of the masses. Another challenge is the integration of the tribal structure into a modern state and sub-state level set-up.

External Dynamics

Likewise there is an external dimension of the integration issue:-

- External actors and elements assisting them for decades are not likely to give up their role as long as they continue to be paid for by their puppeteers. They are likely to remain pliable in the hands of foreign elements who could, off and on, manipulate them to impede the implementation of integration 33.

- Provincial and Federal governments alongside civil society should remain cognizant to the Afghan government’s negative reaction to the merger. It is essential to have a strategy at hand to neutralize cross border attempts to unravel the integration processes.

- Busy international drug trafficking routes pass though this area. Drug barons are likely to pump in money to sponsor the prolongation of the status quo 34. Gun running and human trafficking are other issues 35 that need attention.

If these impediments are managed prudently, the process of integration is likely to offer a wide range of opportunities. Efficient exploration of rich natural resources is likely to generate plenty of resources for developmental uplift and prosperity.

Setting up of “Free Economic Zones” will, most likely, generate jobs for the local inhabitants. This could be done through a three pronged approach: Provincial and State level effort; CPEC integrated approach; and seeking help from the UN, US, EU, etc. for generating sustained financing for Human Resource Development as a prerequisite for sustainable eradication of militancy and terrorism.

The UN should be approached for special resource allocation, through its various organs, for comprehensive development of FATA/ PATA territories – especially infrastructure, governance capacity enhancement and Human Resource Development. The merger is likely to strengthen the international counter terrorism regime significantly; hence the international community should come forward to donate substantially under the counter terrorism effort.

The period 2019-2038 should be designated as the “Era of Transformation, Integration and Development” for a comprehensive uplift of the ex-FATA/PATA territories. To accomplish this objective, “special grants in aid should be allocated for the coming years under a proper monitoring mechanism to rebuild and renovate the basic communication and civic infrastructure. And promised reforms should be implemented phase-wise and in a transparent manner”. 36

The FATA Dilemma: Beyond the 31st Constitutional Amendment

The status of ex-FATA territories and its inhabitants continue to “constitute a core issue”. Over the years, the government of Pakistan has made concerted efforts to mainstream the people and territories of FATA/PATA. The FCR was amended in 2011 37 to exclude some of the harsher punishments, especially group penalties; it incorporated recourse to Riwaj (custom) and provided some facets of Appeal, Wakeel (advocacy) and Daleel (argument) 38. The law of universal franchise has already been extended to FATA since 1997 and political parties were allowed to function in 2013 39. The elections of 2013 and 2018 were held as per the norms of universal franchise under the umbrella of political parties 40. After the merger, the first ever provincial level parliamentary elections were held on July 20, 2019 41. The political rights of the people of erstwhile FATA are now at par with any other part of Pakistan, as the parliamentary seats’ allocation has been on the basis of population alone 42. There has also been progress in setting up of the police and judiciary system in former FATA 43. Seamless integration, however, may be decades away, mainly due to the inclination of the ex-FATA people towards Riwaj (Tribal norms and customs) as their primary law 44. This may also impede their journey towards attaining parity with the rest of the country with regard to Human Rights.

Left at their own, borderlands thrive on informal economies. The resultant unaccounted for wealth leads to the evolution of misplaced power centres controlled by criminals, peddlers, traffickers and warlords, ultimately leading to politics of coercion and terrorism. Development of transnational economic zones under various brand names and evolving Free and Preferential Trade Agreements are some of the ways of mainstreaming borderlands through economic uplift and transformation of the informal economy into a formal economy by applying bare minimum essential regulatory measures. Unfortunately, Pak-Afghan borderlands missed an opportunity when the Americans went back on their project of setting up Reconstruction Opportunity Zones 45.

Managing the Borders/Borderlands

To fulfill their responsibility towards the international community, Afghanistan and Pakistan need to effectively manage their borders. Neither could abdicate this responsibly and hope that criminals, terrorists and third party state and non-state actors would abide by some voluntary code of conduct and desist from undertaking their nefarious pursuits.

Pakistan has traditionally followed benevolent border management practices towards Afghanistan even at the cost of great socio-economic losses and security concerns. Whenever the Afghans were under pressure, due to foreign invasions, the government and the people of Pakistan welcomed them in numbers. As a result of the prolongation of this process the borders existed only on paper. But with the threat of terrorism and the advantage being taken by third party actors – state as well as non-state – to ferment trouble in the heartland of Pakistan, the option of unregulated borders is no longer tenable.

Apparently, time is not yet ripe for achieving a mutually acceptable bilateral border agreement, even though the border’s current management status is the primary issue troubling Pakistan-Afghanistan relations. Unless Pakistan goes ahead with its unilateral actions to manage the border, even if Afghanistan does not do it, the borderlands will remain the way they are. Afghanistan and Pakistan are under obligation by the “United Nations Security Council Resolution 1373” to “deny safe haven to those who finance, plan, support, or commit terrorist acts, from using their respective territories for those purposes against other states or their citizens.” Hence both countries are under obligation to manage their borders effectively.

In the overall perspective, the Pak-Afghan border should be seen as a medium of pragmatic goodwill and a positive leverage by both sides, especially in the people’s context, rather than an instrument or pretext for conflict brewing. Socio-economic development of the border region coupled with political, legal and administrative reforms is a prerequisite for peace, stability and progress.

Once peace returns to Afghanistan, the interim stringent measures would become superfluous and their continuation would be an overkill. At that point and time, both the countries should and must relax undue restrictions and adopt a model close to the European Union or that of US-Canada. This is also what Prime Minster Imran Khan envisages.

After decades of suffering, due to the geographic location, regional and global power politics, lingering insecurity, economic backwardness, illiteracy and political isolation, the people of the Tribal Areas may finally witness a certain level of peace and prosperity through the proposed “FATA Reforms package 2016” 46 and the ensuing “31st Constitutional Amendment”. However, before the promises come to realization, there is a long way to go. Seeing the convolution of tasks, sensitivity of the matters, and far-reaching implications of policy options 47, the road to Tribal areas’ “happy future requires stewardship of the highest order” 48.

Mainstreaming of tribal areas “is easy in the sense that there is broad consensus among the various stakeholders” 49 about it. However, “it is also a challenging task due to the lack of unanimity about the various steps, priorities and the pace of reform. This is quite natural, given the complicated nature of the subject that entails political, social, economic, constitutional, legal and security implications. The possibility of vested interests, both domestic and foreign, sabotaging the proposed package of reforms, cannot be ruled out as a mere hypothesis. There are potent attendant dimensions in the national, regional and international contexts” 50.

Since the FATA “reforms process has entered a new phase following the constitutional amendment, there is even greater need for sustaining consensus among the stakeholders, building an environment of trust, disseminating information, as well as sequencing and prioritizing the reform steps”.

This is “perhaps the most opportune time for the people of FATA/ PATA and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) to frustrate these vested interests and steer the process of integrating FATA into mainstream Pakistani state and society” 51.

Primary focus should be “to ensure that the reform programme conforms to the constitutional requirements. This will not only forestall the plethora of unnecessary litigation that is usually witnessed against such momentous reform initiatives but will also help policy-makers and political leadership” 52 have requisite resolve and poise to continuously move ahead.

Another important area of immediate focus is chalking out an institutional dispensation to secure the smooth transition from the existing system to a substantial merger with KP. The key challenge in this regard “would be how best to balance and secure the legitimate interests of the people of both FATA and KP through such an institutional” set up 53. The common perception is skeptical about governance in FATA/PATA. Context has to be set right by understanding that there are a number of steps in diverse fields which are required to be taken in parallel.

The integration process “entails constitutional, legal, administrative, political and economic readjustments. The whole process, while keeping the public confidence intact, is sure to take some time. So, where unnecessary delay is not called for, haste and rush too would mean further complications” 54.

Facts and figures (for instance, regarding the population of FATA) have been questioned for accuracy and reliability. Residents of ex- FATA/PATA should get a fair deal in terms of resource distribution in the wake of FATA’s merger with KP. At the same time, the people of KP should not feel unfairly treated in this regard. It is essential that “the resources meant for ex-FATA areas be exclusively spent on those areas”. 55

Importantly, the KP government needs to be enabled to handle the additional burden. This entails the allocation of a far greater share in the NFC award for KP. Such measures are likely to help in winning sustained trust and good will of the masses of ex-FATA areas.

Effective border management is another important issue. Durable security should be the overarching objective alongside “special emphasis on addressing the key contributory factors responsible for the ongoing insecurity”. Moreover, “the grievances and sense of frustration prevailing among the local populace due to the collateral damage and hardship caused by numerous military operations must be adequately addressed to transform a sense of inhibition and despondency into a lasting sense of ownership” 56.

The mechanism of distribution of powers at all tiers should be precisely spelled out and rightfully distributed. Local Government elections should be held at the earliest, and at least 50% of the allocated resources should be spent through local bodies, to provide early harvest benefits to the common man. As an interim measure, the Rewaj system could cater to the aspirations of the people as it seeks legitimacy from the tribal Jirgas. Though continuation of the local Rewaj system may be essential for dispute settlement and for maintaining social fabric for an interim period, there are fault lines between the Rewaj and the constitution, particularly with regard to human rights. For instance, women will remain under empowered under the Rewaj system and the underwritten judicial system will remain over shadowed by the Jirga system. Misuse of authority by the civil administration is a serious issue. People need a judicial system which is sufficiently modern enough in content, and yet in harmony with local cultural and traditional norms.

The Head of the FATA Reforms Committee Mr. Sartaj Aziz said “following the constitutional amendment the people of the federally administered tribal areas were now mainstreamed and would enjoy equal rights like other citizens of the country… all the agencies of FATA would now convert into districts and the assistant political agents would now serve as deputy commissioners 57”. He said “Rs1 trillion would be spent on the development of the area over a period of next ten years” 58.

Conclusion

A constitutional amendment is not a magical wand that will integrate the FATA/PATA people into K-P. It is only the first step towards a process. True integration requires the people of FATA to discard the yoke of Rewaj in favour of basic Human Rights, as enshrined in the constitution of Pakistan. This will not be a simple task, but it is a necessary one. Constitutional rights may suddenly be given to these people, but they will mean nothing if people still consider Rewaj as “the supreme law of the land.” In addition, the Jirga will continue as the preferred method of justice for the people of FATA unless we fix our broken court system, which is plagued by delay, corruption and inequity. Women will continue to be invisible in FATA unless mechanisms are introduced to give them a voice that allows for their stories to be heard. We cannot let this historic moment fall flat on its face because we failed to appreciate the long and arduous process that is needed to create true integration. 59 Sustained political will and durable commitment are the corner stones to success. The pace of transformations should neither be too fast to cause socio-economic disruptions, nor too lethargic to lose the steam and allow other elements to derail the process.

ANNEXURE

Durand Line Agreement 60 (November 12, 1893)

Agreement between Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, G. C. S. I., and Sir Henry Mortimer Durand, K. C. I. E., C. S. I.

Whereas certain questions have arisen regarding the frontier of Afghanistan on the side of India, and whereas both His Highness the Amir and the Government of India are desirous of settling these questions by friendly understanding, and of fixing the limit of their respective spheres of influence, so that for the future there may be no difference of opinion on the subject between the allied Governments, it is hereby agreed as follows:

- The eastern and southern frontier of his Highness’s dominions, from Wakhan to the Persian border, shall follow the line shown in the map attached to this agreement.

- The Government of India will at no time exercise interference in the territories lying beyond this line on the side of Afghanistan, and His Highness the Amir will at no time exercise interference in the territories lying beyond this line on the side of India.

- The British Government thus agrees to His Highness the Amir retaining Asmar and the valley above it, as far as Chanak. His Highness agrees, on the other hand, that he will at no time exercise interference in Swat, Bajaur, or Chitral, including the Arnawai or Bashgal The British Government also agrees to leave to His Highness the Birmal tract as shown in the detailed map already given to his Highness, who relinquishes his claim to the rest of the Waziri country and Dawar. His Highness also relinquishes his claim to Chageh.

- The frontier line will hereafter be laid down in detail and demarcated, wherever this may be practicable and desirable, by joint British and Afghan commissioners, whose object will be to arrive by mutual understanding at a boundary which shall adhere with the greatest possible exactness to the line shown in the map attached to this agreement, having due regard to the existing local rights of villages adjoining the frontier.

- With reference to the question of Chaman, the Amir withdraws his objection to the new British cantonment and concedes to the British Governmeni the rights purchased by him in the Sirkai Tilerai At this part of the frontier the line will be drawn as follows:

From the crest of the Khwaja Amran range near the Psha Kotal, which remains in British territory, the line will run in such a direction as to leave Murgha Chaman and the Sharobo spring to Afghanistan, and to pass half-way between the New Chaman Fort and the Afghan outpost known locally as Lashkar Dand. The line will then pass half-way between the railway station and the hill known as the Mian Baldak, and, turning south-wards, will rejoin the Khwaja Amran range, leaving the Gwasha Post in British territory, and the road to Shorawak to the west and south of Gwasha in Afghanistan. The British Government will not exercise any interference within half a mile of the road.

- The above articles of’ agreement are regarded by the Government of India and His Highness the Amir of Afghanistan as a full and satisfactory settlement of all the principal differences of opinion which have arisen between them in regard to the frontier; and both the Government of India and His Highness the Amir undertake that any differences of detail, such as those which will have to be considered hereafter by the officers appointed to demarcate the boundary line, shall be settled in a friendly spirit, so as to remove for the future as far as possible all causes of doubt and misunderstanding between the two Governments.

- Being fully satisfied of His Highness’s goodwill to the British Government, and wishing to see Afghanistan independent and strong, the Government of India will raise no objection to the purchase and import by His Highness of munitions of war, and they will themselves grant him some help in this Further, in order to mark their sense of the friendly spirit in which His Highness the Amir has entered into these negotiations, the Government of India undertake to increase by the sum of six lakhs of rupees a year the subsidy of twelve lakhs now granted to His Highness.

H.M. Durand, Amir Abdur Rahman Khan. Kabul, November 12, 1893.

References

1- Thomas J. Barfield, “Problems in Establishing Legitimacy in Afghanistan”, Iranian Studies, 37, No. 2, Afghanistan (Jun., 2004), pp. 263-293 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. on behalf of International Society of Iranian Studies. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4311624

2- Dr Sultan-I Rome, “The Durand Line Agreement (1893): —Its Pros and Cons”, J.R.S.P. Vol. XXXXI, No.1, 2004. http://www.valleyswat.net/

3- Anwar Iqbal, “Durand Line is recognized border: US”, Dawn, September 11, https://www.dawn.com/news/1206218

4- Hassan Niazi, “The borderlands”, Express Tribune, May 29, 2018. https://tribune.com.pk/story/1721112/6-the-borderlands/

5- Umer Dil (posted by), “Black Law (FCR) in Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan”, Atlas Corps Blog, July 20, 2016. http://www.atlascorps.org/blog/black-law-in-federally-administered-tribal-areas-fata-of-pakistan/

6-Ibid.

7- Associate Professor Udoy Saikia, Dr. Merve Hosgelen, Associate Professor Gouranga Dasvarma, James Chalmers (Lead Authors), “Tomor-Leste National Human Development Report 2018, Planning the Opportunities for a Youthful Population”, United Nations Development Programme ISBN: 978-92-1-126436- 4). http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/2843/978-92-1-126436-4_web.pdf and: Pakistan: Human Development Indicators, UNDP, http://hdr.undp.org/en/%20en/countries/profiles/PAK

8- Hafiz Muhammad Irfan, “End of draconian laws” , Pakistan Today (Editors Mail), August 18, 2011. https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2011/08/18/end-of- draconian-laws/

9- Ibid.

10- Nadir Guramani, “Bill extending PHC, SC jurisdiction to Fata passed by National Assembly”, Dawn, January 12, 2018. https://www.dawn.com/news/1382472

11- “NA passes 31st Constitutional Amendment Bill, bringing FATA into mainstream”, Associated Press of Pakistan, May 24, 2018. http://www.app.com.pk/na-passes-31st-constitutional-amendment-bill-bringing-fata-mainstream/

12- Blog Khyber.0rg. http://www.khyber.org/history/treaties/durandagreement.shtml

13- Iqbal Khan, “Afghanistan’s Durand Line Dilemmas”, The Frontier Post, April 17, 2018. https://thefrontierpost.com/afghanistans-durand-line-dilemmas/

14- Ibid.

15- Naveed Siddiqui, “Afghanistan will never recognise the Durand Line: Hamid Karzai”, Dawn, March 05, 2017. https://www.dawn.com/news/1318594

16- “The Durand Line: History, Consequences, and Future”, “Report of a Conference Organized in July 2007 by the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies and the Hollings Center in Istanbul, Turkey November 2007”.

17- Smith, Cynthia (August 2004). “A Selection of Historical Maps of Afghanistan – The Durand Line”. United States: Library of Congress. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

18- Ahmer Bilal Soofi, “Pakistan-Afghanistan Border Management: A Legal Perspective”, Citizens’ Periodic Reports on the Performance of State Institutions and Practices, Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency, Islamabad, March https://pildat.org/

19- Ibid.

20- Ibid.

21- Ibid.

22- Rahimullah Yusufzai, “Durand line or border” The News on Sunday, June 26, 2016, http://tns.thenews.com.pk/durand-line-border/#.Wa-DmMZRXIU

23- Ibid.

24- Ibid.

25- Ibid.

26- Ibid.

27- A. G. Noorani, “The Durand Line Revised”, Criterion Quarterly, Vol 10, No 1, March 2015. https://criterion-quarterly.com/the-durand-line-revised/

28- “The Durand Line: History, Consequences, and Future”, “Report of a Conference Organized in July 2007 by the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies and the Hollings Center in Istanbul, Turkey November 2007”. P-6

29- Salman Bangash, “Areas of concern: Problems with the Fata merger” , Herald, July, 2018. https://herald.dawn.com/news/1398620/areas-of-concern-problems-with-the-fata-merger

30- Salman Bangash, “Areas of concern: Problems with the Fata merger” , Herald, July, 2018. https://herald.dawn.com/news/1398620/areas-of-concern-problems-with-the-fata-merger

31- Ibid.

32- Ibid.

33- Ibid.

34- Senator Sehar Kamran, “Evolving Dynamics of FATA: Reflections on Transformations”, ed, Noel I. Khokhar, Manzoor Ahmed Abbasi, Ghani Jafar. September ,2014, National Defence University (NDU) , Islamabad & The Centre for Pakistan and Gulf Studies (CPGS) Islamabad, http://seharkamran.com/wp- content/uploads/2016/07/Final-Book-FATA.pdf

35- Ibid.

36- Salman Bangash, “Areas of concern: Problems with the Fata merger” , Herald, July, 2018. https://herald.dawn.com/news/1398620/areas-of-concern-problems-with-the-fata-merger .

37- “The Frontier Crimes Regulations (Amended in 2011)”, The Institute for Social Justice, Islamabad, http://www.isj.org.pk/the-frontier-crimes-regulations- amended-in-2011/

38- Ibid.

39- Mian Abrar, “FCR amended, political parties allowed in Tribal Areas” Pakistan Today, National, August 13, 2011. https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2011/08/13/fcr-amended-political-parties-allowed-in-tribal-areas/

40- “Pakistani general election, 2013”, WikiVisually, https://wikivisually.com/wiki/2013_Pakistani_general_election

41- “Election commission says will consider relocating ‘sensitive’ polling stations for tribal belt elections”, Arab News, July 06, 2019. http://www.arabnews.pk/node/1521501/Pakistan

42- Ibid.

43- “Authorities take steps to introduce policing in Fata”, The News, October 13, 2018. https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/380233-authorities-take-steps-to-introduce-policing-in-fata

44- Muhammad Zubair, “Mainstreaming Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA): Constitutional and Legal Reforms” Constitutionnet, 14 June 2017. http://constitutionnet.org/news/mainstreaming-pakistans-federally-administered-tribal-areas-fata-constitutional-and-legal

45- This bill was introduced in the 111th Congress (January 6, 2009 to December 22, 2010. Legislation not enacted).

46- “Implementation of FATA Reform Package, Setting the Priorities”, Policy Brief, Institute of Policy Studies, Islamabad, IPS Brief No: PB 2017-III-MH, March 22, 2017. p1-5.

47- Ibid.

48- Ibid.

49- Ibid.

50- Ibid.

51- Wajih Abbasi, “FATA: abolished and merged”, Daily Times, May 31, 2018. https://dailytimes.com.pk/246758/fata-abolished-and-merged/

52- “Implementation of FATA Reform Package, Setting the Priorities”, Policy Brief, Institute of Policy Studies, Islamabad, IPS Brief No: PB 2017-III-MH, March 22, 2017. p1-5.

53- Muhammad Zubair, “A Single Polity at Last? Pakistan’s Unfinished Efforts to Mainstream Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA)”, Constitutionnet, July 18, 2018. http://www.constitutionnet.org/news/single-polity-last-pakistans-unfinished-efforts-mainstream-federally-administered-tribal-areas

54- “Implementation of FATA Reforms Package: Setting the Priorities”, IPS Brief No BP-2017-III-MH. Institute of Policy Studies, Islamabad, https://www.ips.org.pk/implementation-fata-reforms-package-setting-priorities/

55- Ibid.

56- Mairajul Hamid Nasri, “Strategizing Implementation of FATA Reforms Package”, World Times. May 8, 2017. http://jworldtimes.com/jwt2015/magazine-archives/jwt2017/may2017/strategizing-implementation-of-fata-reforms-package/

57- “Implementation of FATA Reform Package, Setting the Priorities”, Policy Brief, Institute of Policy Studies, Islamabad, IPS Brief No: PB 2017-III-MH, March 22, 2017. p1-5.

58- Ibid.

59- Hassan Niazi, “The borderlands”, Express Tribune, May 29, 2018. https://tribune.com.pk/story/1721112/6-the-borderlands/

60- Blog Khyber.0rg. http://www.khyber.org/history/treaties/durandagreement.shtml