Pakistan is a country formed as a result of a struggle of a minority for religious, social and political freedom in India under the British rule. Yet, the question of religious freedom for minorities residing in the now Muslim majority state remains in limbo. Pakistan is home to a diverse religious minority. According to the most recent survey in 2017, 96 percent of the total population is Muslim while the remaining 4 percent constitute 1.6 percent Hindu, 1.6 percent Christian, 0.2 percent Ahmadi, and 0.3 percent others that include Baha’is, Sikhs, and Zoroastrians1. The founding father of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, envisioned Pakistan to be a progressive, tolerant and democratic state which, while retaining its Muslim majority, would grant equal citizenship to its non-Muslim segments. Therefore, in his address to the first constituent assembly he stated, “You are free; you are free to go to your temples. You are free to go to your mosques or to any other places of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion, caste or creed—that has nothing to do with the business of the state…We are starting with this fundamental principle: that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one State.”

However, over the years, Pakistan has seen a demolition of these constitutional values. Minority communities have been subjected to violence, bigotry and social exclusion. State and societal level failures to create an environment of tolerance, equality, interfaith harmony and social justice can be attributed to various neglectful and myopic policies of the past. The issue of forming a collective national identity after independence has been of crucial importance yet it remains to be resolved. Vested interests of individuals to muster support and legitimacy for their rule have banked on the use of religion. This reliance on religion to cultivate a pseudo-national identity has not only failed to unite the society time and again but has also further marginalized minority religious communities of the country. The country, even after 75 years of existence, has not been able to truly represent the white portion of its flag.

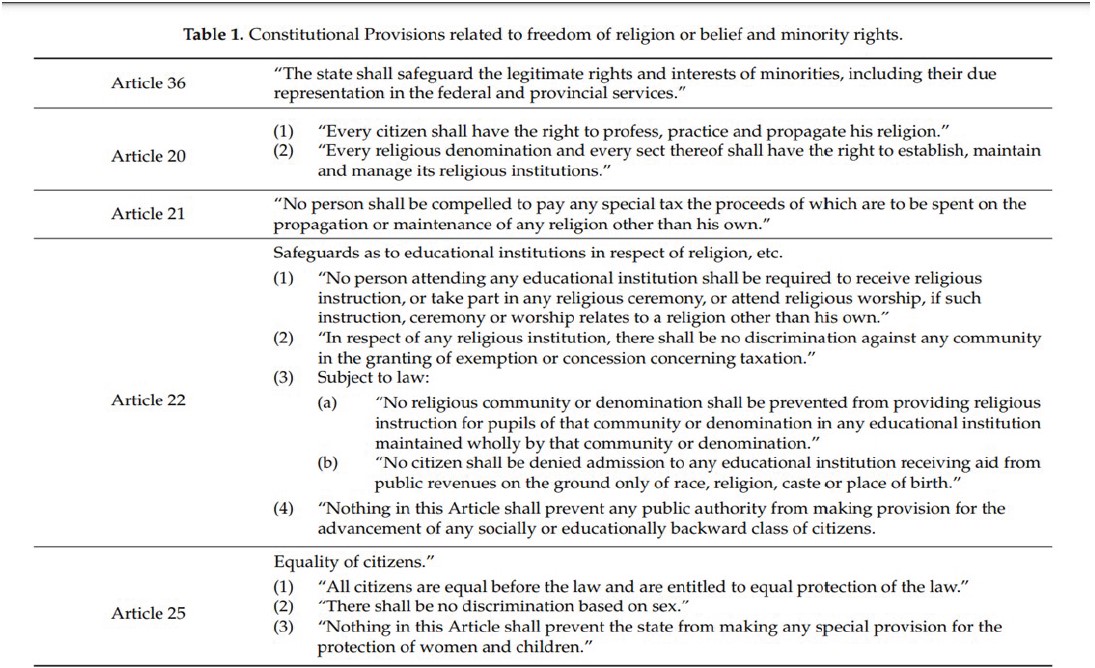

Despite all these issues, the constitution of Pakistan provides several clauses to ensure equal status to minorities in Pakistan. Under Articles 9, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, and 20: the constitution proclaims fundamental rights to all the citizens of Pakistan without any discrimination. While under Articles 11, 21, 22, 25, 26, 27 and 36 “The Constitution also proclaims the equality of all citizens before the law, irrespective of race, religion, caste and sex. However, the on ground implementation of these provisions need attention to make equality and fair play, a basic right, enjoyed by every citizen”2.

Table 1. Constitutional Provisions related to freedom of religion or belief and minority rights.

CHALLENGES FACED BY RELIGIOUS MINORITIES

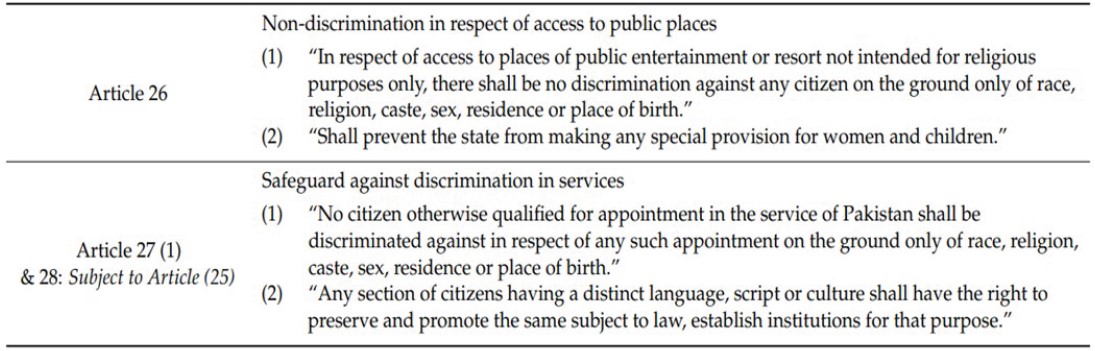

Vigilantism and blasphemy are intertwined, morphing into a complex problem in Pakistan. The precursor of the present-day blasphemy law is the one and a half century old Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC) which dealt with offences related to religion. Section 295 of the IPC was particularly concerned with “intentional damage or defilement of a place or object of worship”. After independence, Pakistan retained and inherited the Penal code and only 10 reported judgements under 295-A, relating to offences against religion, were reported between 1947-1977. Most of the cases were dismissed on failing to meet the prerequisite of ‘deliberately and maliciously’. Moreover, most of the cases registered were of Muslims against Muslims or Non-Muslims against Muslims. However, During Zia’s regime, between 1987-86, several anti-blasphemy laws and acts were incorporated into the Pakistan Penal Act with punishments ranging from imprisonment to fine and even capital punishment. Between 1987 – 2017, 1500 individuals were charged with blasphemy out of which 75 were killed3.

Out of the accused, 46.3% belonged to the dominant Muslim community, whereas 51.9% were from all the minority communities combined. Yet, this percentage also depicts that 51% of the accused belonged to a mere 4% of the population of the country. However, to date, not a single person charged with blasphemy has been executed. On December 3, 2021, Priantha Kumara, a Siri Lankan Christian Manager of a factory in Sialkot, was attacked and brutally killed by a mob on the accusation of committing blasphemy by removing Tehreek- e-Labbaik’s poster that had some prayers written on it.4 This brings to fore the important aspect that the law is often used as a tool to settle personal vendettas, not only against the minorities but the Muslims as well, whereby the accused is often subjected to street vigilantism instead of trial in the court of law.

Societal culture in Pakistan draws its roots from South Asian stock. The present Christian locals are primarily a convert community from the Hindus of the Indian sub-continent. Though Islam propagates equality of all classes and castes before God, the social influence remains strong in the routine conduct of all communities. Members of minority communities are frequently looked down upon and socially stigmatized as low caste untouchables, often derogatorily referred to as ‘chura’. Minority communities are at the bottom rung of society, being typically poor with limited resources for education and prospects for social upward mobility. According to a survey conducted by Poza (2011), 9 out of 10 Hindu women are illiterate, whereas the women literacy rate in the country is 58%.5

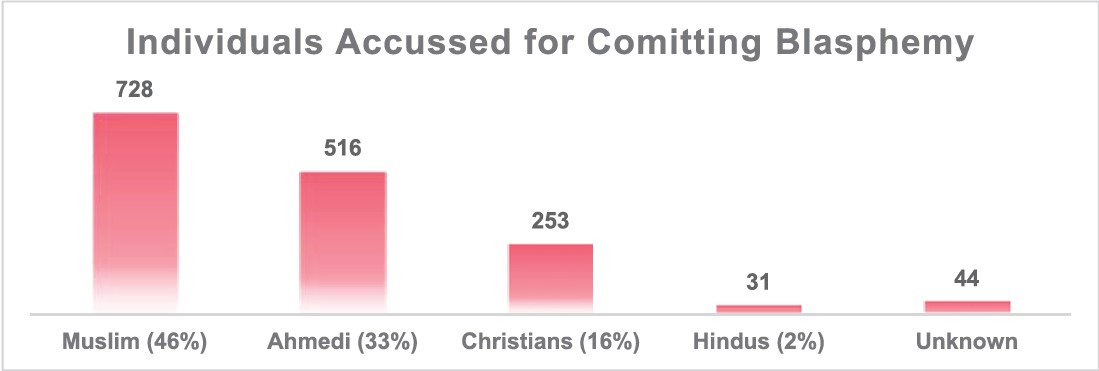

The constitution states that public and private sector employment is the right of every citizen. The federal and provincial governments have set a quota of 5% for government sector jobs. However, the Supreme Court last year raised concerns over the government’s failure to implement the quota. While the media reported 30,000 reserved positions vacant across the country.6 A vicious cycle of poverty, low class status and social prejudices lead to exploitation of minorities that is represented through the low number of vacancy occupation rates. Minority groups are mostly employed in low end jobs with systematic exploitation and neglect instilling a feeling of humiliation. This is illustrated with the under mentioned info graph.7

Discriminatory ad posted KPK Government Breakdown of BPS 01 in Punjab Assembly

Violence perpetrated against minorities includes terrorism as the most lethal in terms of exacting human cost and striking fear amongst the minorities in Pakistan. According to the US Commission on International Religious Freedom Annual Report 2013, 200 attacks were perpetrated against religious groups and 1800 fatalities were recorded in religion- related acts of violence. However, the trend and casualty figures have begun to subside in the wake of successful military operations. Religion- based fatalities registered only 228 casualties in 2019 in contrast with 11,704 in 2018.8 The perpetrators of such violence are diverse, ranging from outright terrorist groups like ISKP, TTP, Laskar e Jhangvi, etc, to mainstream religious cum political leaders inciting mobs to commit acts of violence for their own vested interests.

Furthermore, the Christians and Hindus in the country are considered proxies of the west and India by the masses. Therefore, they have to often face the brunt of animosities against the western world and India.

Another aspect of violence is far more sinister in terms of negative social impact, i.e forced abduction of minority girls and marrying them to Muslims against their consent. Every year approximately 1000 girls between the ages of 12-25 from minority communities are abducted and married to their Muslim abductors.9 Last year the parliamentary committee on religious affairs and interfaith harmony rejected a draft bill proposing anti-forced conversion law claiming that the environment was unfavorable to promulgate it and it would make minorities more vulnerable. Thus, leading to resentment and hopelessness within the minority community.

UNDERLYING CAUSES FOR RELIGIOUS INTOLERANCE

The escalation of these radicalized and extremist actions can be attributed to several systematic flaws, including impaired justice system, negligence of law enforcement agencies, lack of accountability, propagation of radical and extremist narratives, and a fragile education system. The judicial system is one of the primary organs of the state that ensures equality and fairness amongst the citizens. Unfortunately, in the case of Pakistan it has not been able to function independently and justly. Legal observers and minority representatives have claimed that undue threats from extremists and fear of vigilantism by protestors force the lower courts to delay proceeding and adjudicating blasphemy cases which leads to some suspects spending years in detentions. Furthermore, higher courts overturn decisions of lower courts only after the convicted have spent years in prison. On June 3, 2021, the Lahore High Court (LHC) acquitted and released a Christian couple, Shafqat Emmanuel and Shagufta Masih, from Punjab’s Toba Tek Singh District. They were arrested in 2013 on charges of blasphemy. In April 2014, a lower court had sentenced the couple to death and fined them 100,000 rupees each.

Similarly, there is resentment against law enforcement agencies for their negligence and lack of apathy. Although the government and law enforcement agencies have intervened in many cases of abduction and forced conversions, there is rarely any measure taken against the perpetrators of such crimes. Such leniency and lack of deterrence further encourages the offenders.

Education is one of the most important tools in nation building. The lack of access to quality education in a country like Pakistan, where half of the population is below the age of 17, has grave consequences. Numerous studies have shown how education, amongst various other factors, reduces the chance of conflict and builds a sense of tolerance. One research on Pakistan has found that the higher the level of education obtained by respondents, the less likely they are to support the Taliban and sectarian groups.10 With regard to this, the government has passed the bill of free and compulsory education for every child between the ages of 5 to 16 years but the implementation of this law still has to overcome many hurdles. The revised education policy in 2009 had also aimed to increase the education expenditure from 2.7% of GDP to 7% of GDP.

Furthermore, focus should not be limited to the access of education but also the provision of quality education that promotes peace and tolerance. One of the primary purposes of education is to eliminate all differences amongst students and promote a national identity detached from religious identity. The education system in Pakistan has been long critiqued by multiple scholars for its inadequacy in building critical thinking. Hoodbhoy argues that the education system in Pakistan emphasizes on ritual, tradition, and submission to authority rather than analytical reasoning and problem solving.11 In ‘The State of Curricula and Textbooks in Pakistan’, the editors A. H. Nayyar and Ahmed Salim claim that the existing text books promote binary learning over critical thinking that foster narrow worldviews and opinion.12 In addition, certain contents in the textbooks of primary school classes promote prejudice against believers of other faiths. This infiltration of negativity towards minorities enhances as the child develops. The case of Mashal Khan and Noureen Laghari are alarming signs of dehumanization of our higher education system that focuses more on technical education, leaving behind the concepts of morality.

Moreover, different researchers, including Christine Fair, Tariq Rahman and Saleem Ali, have pointed out the relation between religious intolerance and Madarassah education. These institutions are known to highlight differences in faith and, as a result, encourage disharmony within society.13 In addition, by enforcing opinions on impressionable minds, these systems are incorporating religious bigotry at a very young age. The government has developed policies for bringing reforms in the Madarassah system and has encouraged Madrassahs to incorporate contemporary knowledge along with religious education. The complete implementation of these policies and their fruitful results are, however, yet to manifest.

THE OPPOSING NARRATIVE

The flip-side of this discourse places the above-mentioned crimes, violence and prejudices committed against religious minorities into perspective. The culprits do not represent the whole society but are a small fanatic fraction that have gathered disproportionate attention. According to a survey conducted by World Public Opinion. org in collaboration with the U.S. Institute of Peace, ‘Eighty-one percent of the survey results say that it is important for Pakistan to protect religious minorities and around 75-78 percent say that attacks on specific religious minorities (Ahmadiyya and Shi’a) are never justified’.

In the same vein, the available literature on religious minorities disproportionately focuses on the blasphemy laws, and the resultant persecution and discrimination. This is flawed as it represents a single dimension of their lives in a Muslim majority country. Wallbridge, in his landmark book ‘Christians of Pakistan’, mentions that Christians are portrayed as ‘a beleaguered community, some of whom constitute the wretched of the earth, simply surviving from day to day while facing a multitude of humiliations’. This lopsided narrative is problematic for several reasons. Firstly, it ignores the fact that many of the traumatic experiences faced by the minorities are not limited to them but are rather shared by many citizens. They are the victims of a failing legal system, scourge of terrorism and absence of rule of law in many areas. However, due to their much smaller number and lack of access to resources to cope with the trauma, they are disproportionately affected by these incidents. Therefore, studying their experiences of violence and prejudices under the simple lens of intolerance, allegedly associated with Islam, is distorted. Instead, they should be understood in the larger context of a failing state, the rise of authoritarianism and resurgence of nationalistic ideologies.14

Additionally, the existing narrative of minorities being oppressed and marginalized obscures the aspect of their other multiple shared identities with the larger populace. Their common ethnic, historical, linguistic, cultural and gender ties place them in a broader spectrum of society. Moreover, their political allegiance, social class, occupation and caste lays the foundation of connection with their fellow Pakistanis. A glaring example of this is the Tharparkar District, where the Hindus comprise 40 percent of the total population and live in harmony with the Muslims. Makki (2015) claims that in the local towns of Tharparkar dessert, Hindu and Muslim communities form a neighbourhood where one can see the two distinct religious identities adopting characteristics of each other. Despite being a deprived and poverty-stricken region, it contradicts the major social theories of conflict.15 Similarly, the annual Mela in the village of Mariamabad near Sheikhupura is attended by millions from different faiths. This event is another example of spiritual connections shared by local Sufis, Christians and Hindus and offers us valuable insight to explore the factors which enable the manifestation of a peaceful co-existence that can be further utilized to bring inter-faith harmony nationwide.

RECOMMENDATIONS

A panel of renowned religious scholars from all sects of Muslim community and public figures should be constituted under the ambit of Ministry of Religious Affairs. The panel should hold regular media outreach to masses and convey the real message of Islam in terms of treatment meted out to the minority community. The ownership of religious fatwas and jurisprudence needs to be regulated by the government. The initial cues can be drawn upon from Paigham-e-Pakistan and subsequently expanded to mould public opinion, which is more inclusive, being in line with the national objectives of Pakistan.

A modern progressive society cannot function effectively if plagued by neo-colonial conduct towards the lower strata of society. Media has an important role in highlighting the grey areas and creating an environment which rejects oppression in all its forms. All derogatory content towards minorities should be properly analyzed before publishing and heavy fines should be imposed by PEMRA on defaulters.

Vigilantism and violence in all forms perpetrated against minority communities can only be countered with legal strong arm. Special minority courts should be established at appropriate levels to speed up delivery of justice. A bench should also be established to facilitate perusal of cases related to minority family laws. To prevent forced conversions, a bill with necessary measures should be passed at the national level under the recommendations of the ministry of religious affairs and interfaith harmony.

CONCLUSION

Pakistan remains a vulnerable place for minorities because of hate crimes, discrimination, social injustice and violence. However, the threats posed to the minority communities are from a small fraction of society that has gained national and international attention. The majority wants a tolerant and egalitarian society. Moreover, the constitution and other state policies aim to develop a state safe for all citizens. The recent establishment of a special police unit for the protection of minorities and their religious sites in all provinces along with the implementation of the National Action Plan to curb terrorism and hate speech are steps taken to build confidence among religious minorities. Yet, more needs to be done at the structural and functional level to strengthen state institutions and foster a culture of peace and harmony.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- ACCORD – Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and 2021. “Pakistan-Religious- Minorities-March-2021”. https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2047750/ACCORD-Pakistan-Religious-Minorities- March-2021.pdf .

- Curtis, Lisa, and Haider Mullick. 2009. “Reviving Pakistan’s Pluralist Traditions To Fight Extremism”. The Heritage https://www.heritage.org/asia/report/reviving-pakistans-pluralist-traditions-fight-extremism.

- Fair, C. Christine. 2008. The Madrassah Challenge. Washington,

D.C.: United States Institute of Peace. - Fair, C. Christine. The madrassah challenge: Militancy and religious education in Pakistan. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2008.

- Fuchs, Maria-Magdalena, and Simon Wolfgang Fuchs. 2019. “Religious Minorities In Pakistan: Identities, Citizenship And Social Belonging”. South Asia: Journal Of South Asian Studies 43 (1): 52-67. doi:10.1080/00856401.2020.1695075.

- Hoodbhoy, Pervez. “Education reform in Pakistan–Challenges and prospects.” Pakistan: Haunting Shadows of Human Security, edited by Jennifer Bennett 58 (2014).

- Khalid, Iram, and Muhammad Rashid. 2022. “A Socio Political Status Of Minorities In Pakistan”. Journal Of Political Studies Vol. 26 (Issue – 1, 2019).

- Makki, Muhammad, Saleem H. Ali, and Kitty Van Vuuren. 2015. “‘Religious Identity And Coal Development In Pakistan’: Ecology, Land Rights And The Politics Of Exclusion”. The Extractive Industries And Society 2 (2): 276-286. doi:10.1016/j. exis.2015.02.002.

- Mehfooz, Musferah. 2021. “Religious Freedom In Pakistan: A Case Study Of Religious Minorities”. Religions 12 (1): 51. doi:10.3390/rel12010051.

- Nayyar, Abdul Hameed, and Ahmed Salim. “The subtle subversion.” Retrieved August 8 (2022): 2013.

- OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM 2002“2021 Report On International Religious Freedom: Pakistan.”

- Poza, Rebecca.2010.“Pakistan’s Institutionalized Discrimination Against Religious Minorities”. Huffpost, , 2010. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/pakistans-institutionaliz_b_794230.

- Rehman, 2021. “Attitudes Towards Religious Minorities In Pakistan: Gaps In The Literature And Future Directions”. PAKISTAN LANGUAGES AND HUMANITIES REVIEW 5 (II): 345-359. doi:10.47205/plhr.2021(5-ii)2.28.

References

- (OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM 2022)

- (Mehfooz 2021)

- (ACCORD – Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation 2021)

- (OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM 2022)

- (Poza 2010)

- OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM 2022)

- https://www.nchr.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Minority-Report.pdf

- (Mehfooz 2021)

- https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/religionglobalsociety/2022/01/pakistans-dilemma-of-forced-conversions-and-marriages-put-minority-women-at-risk/

- (Fair 2009)

- (Hoodbhoy 2014)

- (Nayyar and Saleem, 2003)

- (Curtis and Mullick 2009)

- (Fuchs and Fuchs 2019)

- (Makki, Ali and Van Vuuren 2015)