by Özer Khalid†

*The views expressed here are empirically validated researched facts from a broad array of fully referenced sources. The comments made neither necessarily reflect those of the author nor those of Criterion Quarterly.

Those seeking to academically reference this article for their research may do so as follows: Khalid, Ozer (2022) How South Asia Cushions the Blow of Western Sanctions on Russia, Criterion Quarterly, March 2022.

† The author is a Senior Consultant, geo-strategist, a regular CQ contributor and a counter terrorism expert and can be reached at [email protected] and tweets @OzerKhalid

Abstract

Financial sanctions levied by American and NATO allies tighten the noose around Russia’s neck. As war infernally rages on in Ukraine, Russia’s economy suffers under the weight of unparalleled punitive measures from the US, UK and EU administrations. This financial bow aims the arrow straight in the heart of Russia’s banking sector.

This CQ report explores how South Asia and China is simultaneously preparing mitigating measures to cushion the severity of Western sanctions regime against Russia – Author.

The Russia-Ukraine War – An Impact on Pakistan’s Economic and Energy Markets: The Sanctions Blowback

Prime Minister Imran Khan announced that he will slash fuel and electricity prices to counter a hike in international energy prices owing to the Russian-Ukrainian conflagration.

In an across-the-board televised speech, Mr. Khan stated that he would slash gasoline and diesel prices to the tune of 22 cents a gallon and electricity rates by approximately 3 cents per kilowatt-hour. This sudden announcement arrives at a time when Mr. Khan faced rising political discontent domestically, especially as opposition political parties congregate in protest rallies,1 vociferously protesting the country`s inflation and economic woes.

Fuel and electricity prices soared steeply in Pakistan as the ruling PTI government conducted excruciating (but necessary) reforms under a bailout package by the International Monetary Fund. In February 2022, the IMF,2 under its Extended Fund Facility (EFF), approved3 releasing a tranche of $1 billion of a $6 billion package after long-drawn-out negotiations with Pakistani officials.

Critics reason that these sudden announcement of reduction in petrol and electricity prices are a hasty counterweight to the rising political inferno by opposition parties seeking to mount a parliamentary motion of no-confidence against the Prime Minister. These cuts will (at best) offer temporary relief, exacerbate inflationary pressures on the economy and remain in effect until June 2022, as the next budget kicks in.

“The subsidies will only add to the fiscal deficit and are completely contrary to the agreements reached with the IMF,” stated Uzair Younus, the director of the Pakistan Initiative at the Atlantic Council. He further stated, “The increased deficits and borrowing will pressure the rupee in the coming weeks, crowd out private investment, and create medium-term economic instability and vulnerabilities.”4

Energy prices in Pakistan, particularly the short-term soaring of crude oil, liquefied natural gas (LNG) and coal prices, have exacerbated the country’s current account balance. Pakistanis will further feel the pinch of globally soaring gas prices in the aftermath of the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian military battle, adversely impacting Pakistan’s impending energy challenges.

Brent oil crude futures already peaked to a seven-year high of $100 a barrel owing to the Russia-Ukraine escalation and is estimated to inch ever closer to $1205 with Russian armed conflict and Covid Omicron variant related supply chain bottlenecks. If Russian oil flows are halved due to the war, crude oil could surge to USD $ 150 a barrel/150 BBL6 by 20237.

Power producers commenced stockpiling coal, owing to the forthcoming gas disruptions to the European Union. This augmented coal prices, currently hovering at $196 per tonne, up 43 percent since January 2022.

As global energy prices sky-rocket, the prognosis is bleak for Pakistan. A cash-strapped government will have no other option but to pass on the increased international energy prices to the consumers. This will further fuel the flames of their financial pain—ratcheting up the prices of transport, food and other sustenance items at a time when affordability is a key concern for a majority of Pakistanis8.

Though the Russian-Ukrainian war brews thousands of miles away from Pakistan, yet in a globally inter-connected world Pakistan will be intensely jolted by the pricing and scarcity shock-waves and must be ready for that. The Ukraine-Russia conflagration will cause rallies in the (international) prices of food, energy, commodities and semiconductor chips. A shortage of semiconductor chips will adversely impact Pakistan’s IT and automotive sectors.

Salting the wounds even more, Pakistan will take an additional hit as the bulk of its wheat imports emanate from Ukraine. Thirty-nine per cent of Pakistan’s total imported wheat came from Ukraine in 2021.

In addition to wheat imports, Pakistan also buys 37 percent of its corn starch from Ukraine. And in exports, Ukraine has a 28 per cent share in the foreign sales of Pakistani polyester staple fibres.

Certain analysts reason that the increase in import bills due to elevated food, energy and other commodity prices will push Pakistan`s current account deficit—which reached 5.7 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the first half of the current financial year—higher and exert pressure on the exchange rate.

If the trade deficit remains on this trajectory, the State Bank (SBP) will raise the cost of borrowing, which had hitherto remained unchanged at 9.75% in February 2022, to curb local demand, cool off inflation and protect its foreign exchange reserves9.

In 2021 Imran Khan’s government ditched the International Monetary Fund programme and splashed out a liberal budget in June to swiftly grow the economy to reap electoral dividends ahead of the 2023 general elections. As expected, this adversely affected the current account deficit in the initial part of the fiscal year, forcing the government to return to austerity measures with the lender of last resort, (IMF) and revert to the USD $ 6 billion program10 to mitigate pressing external account susceptibilities.

Islamabad had to abide by the stringent terms and conditions of the IMF that included discontinuing tax exemptions and amnesties, augmenting the petroleum development levy on fuel, hiking electricity prices and revoking fiscal and monetary stimulus for industry for the IMF program to be relaunched in February 2022.

The IMF lending initiative, which culminates in September 2022, still requires the ruling PTI government to elevate personal income tax rates and increase electricity prices to secure the pending loan amount of USD $3 billion over the next seven months11. This is a bitter but necessary pill to swallow.

For the immediate present, Pakistan is compelled to either buy expensive LNG, if and when available, to satisfy the fuel requirements of the country’s power sector and industry, or lower spot gas imports to protect its dwindling foreign exchange reserves, currently at $23.72 billion as per the State Bank of Pakistan.

At present, the only mitigating factor is the supply of seven cargoes per month via Qatar, currently at nearly a third of the spot LNG price, under the auspices of two long-term LNG sale and purchase agreements. The country’s cumulative need, however, is a minimum of twelve to fourteen cargoes a month.

Currently, the spot purchase price of a cargo costs a staggering USD $ 80m against the $26m to $30m that Pakistan pays for a cargo under its LNG agreements with Qatar. Even global suppliers like Gunvor and ENI, with whom Pakistan`s government has contracts for the supply of a single LNG cargo per month, have reneged12 on their supply commitments ever since global LNG prices soared given the onset of the cold weather13.

Simmering Russian-Ukrainian tensions exacerbate the elevated gas prices, forecasted to remain high over the coming months. European prices have peaked from $24/MMBtu to $40/MMBtu14. It is high time that decision-makers start broadening Pakistan`s energy portfolio and sources as energy security remains key to sovereignty.

What occurs in global geopolitics and international commodity prices is beyond the remit of Pakistan`s government. It must, however, intensify multi-pronged formulations toward long-term energy policies that factor in the risk premiums of changing market fundamentals in the wake of the Russian-Ukraine clash.

Over the short term, seemingly, Pakistan will need to temporarily replace LNG15 with furnace oil and diesel until gas prices stabilize. But longer-term energy security requires that the government conjures up a meaningful strategy to lure investments in the country’s vast domestic oil and gas exploration industry for new discoveries while simultaneously enhancing incentives for the use of renewable energy to confine dependence on costly fuel imports.16

Moscow is, therefore, being considered as a new participant in Pakistan’s geopolitical calculus, with a potential to cultivate a robust relationship focused on the energy, economic and military sectors.

High on the Pakistan-Russia agenda is the Pakistan Stream gas pipeline, a proposed 1,100km (684-mile) pipeline coursing through the port city of Karachi to the central Punjab province of Kasur. This project was initiated in 2015 but encountered multiple lags until newer agreements were drafted in 2021.

Being a net importer of energy, Pakistan will benefit from this pipeline, as it will incorporate new sources of natural gas and transfer it to the heavily populated industrialized north. The Pakistan Stream Gas Pipeline is evolving into a vital strategic tool for Moscow to spearhead its new South Asian foreign policy vector.

Imran Khan’s recent visit, therefore, was part of the consistent initiatives by Moscow and Islamabad to bury the bitter hatchet and foray into a new diplomatic entente cordiale. Pakistan expects President Putin to pay a reciprocal visit to Islamabad later in 2022. If that transpires, it will end decades of overt and covert initiatives by both nation-states seeking to paradigm shift their rapport from being bitter cold-war rivals to strategic long-term partners.

An Overview of Western Sanctions on Russia

Financial sanctions levied by American and NATO allies tighten the noose around Russia’s neck. As war infernally rages on in Ukraine, Russia’s economy suffers under the weight of unparalleled punitive measures from the US, UK and EU administrations. This financial bow aims the arrow straight in the heart of Russia’s banking sector.

This CQ report explores how South Asia is simultaneously preparing mitigating measures to cushion the severity of Western sanctions regime against Russia.

Western authorities are trying to prevent Putin from tapping into a lucrative $630 billion war chest Moscow stockpiled prior to invading Ukraine.

This latest package includes sanctions on Russian banks, debt and equity limitations on state-owned enterprises, and unparalleled international export controls aimed at reducing Russia’s high-tech imports by half.

The Russian pipeline Nordorm-2 also received a setback in the milieu. It is more of a setback to Germany than Russia. The former would have received gas at a much cheaper rate than the one offered by America. As per estimates, American gas is ten times more expensive than Russian.

The Biden Administration envisaged that American sanctions, complemented by similar initiatives by the European Union and other U.S. partners, would catalyze Russia’s isolation from the world economy. Lower living standards and reduced financial potential would decline Putin’s local electoral base, mobilizing attention and resources away from foreign policy.

Regarding the economic burdens of war, Moscow can, in the immediate present, weather the financial storm with it’s $ 630 billion reserves and only twenty percent debt to GDP liability. The sanctions imposed by America and the European Union are pinching Russia which is also retaliating by imposing a ban on the supply of energy to most of Europe, notably Germany. Oil prices already surpassed USD $ 100 per barrel, unleashing panic in the global commodity markets, especially in developing countries such as Pakistan.

Sanctions notwithstanding, Russia’s central bank has been calculatedly stockpiling foreign reserves ever since Russia’s previous Ukraine invasion during Crimea’s annexation in 2014. Since then, Russia’s foreign currency and gold reserves nearly doubled, ballooning to $630 billion today from $368 billion17 since 2014.

Building foreign reserves was a pre-meditated calculus by the Kremlin to hedge Russia’s economy vis-à-vis sanctions, by offering the central bank key ammunition to protect the value of the ruble. The ruble lost half its value versus the U.S. dollar when Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, forcing Russia’s central bank to spend $130 billion to stabilize the currency. Crimea is strategically important to Russia since the Black Sea Fleet, which is Russia’s means of projecting power in the Mediterranean (therefore Europe), is located, by long-term lease, in Sevastopol, Crimea.

Under the West’s 2022 sanctions regime, the foreign reserves freeze hasn’t cut Russia off from its foreign currency totally. The embargo still permits Russia to utilize its reserves for crucial energy payments, which keeps open a lifeline18 for the central bank. The West’s Central Bank squeeze excludes the energy sector, thereby preventing a total collapse of Russia’s economy. Russia’s central bank can also still access 13% of its reserves held in Chinese yuan19 as China is both overtly and covertly supporting Russia’s economy against western embargoes.

Beijing is the only main issuer of foreign reserve currencies that hasn’t cut Moscow off. China’s banking regulator said it would “not participate” in sanctions against Russia, adding that sanctions “do not work well and have no legal grounds.”20

However, the ruble currency nose-dived 29% vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar as America and its allies targeted Putin’s government’s approximately USD $600 billion in reserves stored by the Central Bank of Russia, severing Russia’s arteries to the global financial system21. A punitive measure that was dished out to Afghanistan a few months back.

An estimated $300 billion of Russia’s reserves are stashed away in the U.S., Europe, and ally states. Though Moscow retains billions of dollars worth of gold within its borders, experts say Moscow will find few willing gold buyers, given the crushing sanctions. They own it but cannot use it.

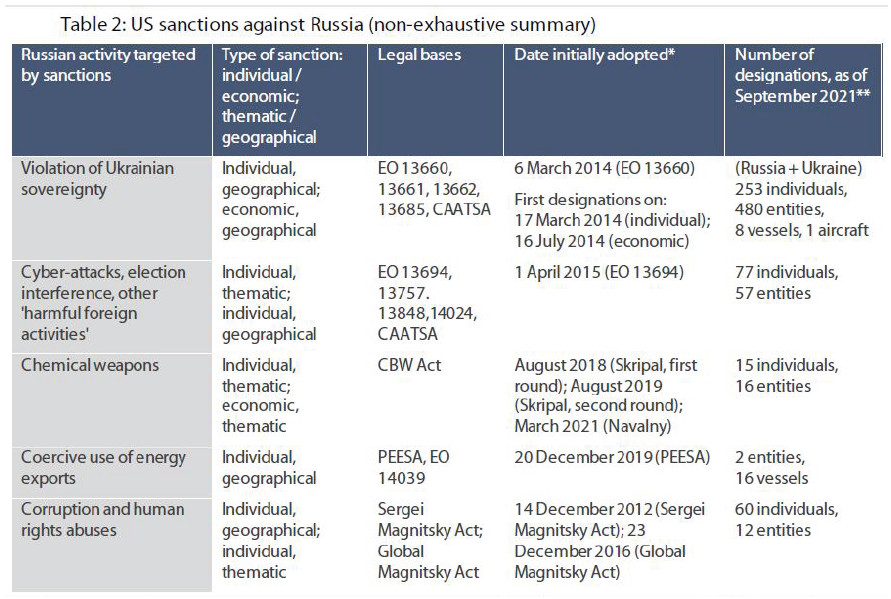

Source: European Parliamentary Research Services, February, 2022.

Source: Congressional Research Service, October (2021) Office of Foreign Assets Control.

Previous U.S. sanctions and lawfare vis-à-vis Russia included: Protecting Europe’s Energy Security Act (PEESA), the Sergei Magnitsky Act and Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act (CAATSA). In February 2022, some Russian banks were banned from accessing the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT)—a payment platform, a standardized and secure messaging system used by banks to send and receive money transfer instructions, hastening cross-border payments.

Iranian banks were also banned from SWIFT in 2019 in the aftermath of US sanctions. Washington has hitherto targeted the central banks of North Korea, Venezuela, and Iran with sanctions. The U.S. has, however, never levied such harsh punishments, with the backing of so many other nation-states, on an economy the size of Russia’s.

In 2021, the U.S. froze foreign reserves held by Afghanistan’s central bank to curtail the Taliban from accessing the funds after it seized the reins of power in August 2021. This was meant to be used as leverage against the Taliban. The U.S. has also frozen the foreign exchange reserves of Iran, Syria, and Venezuela before, yet none of the previous targets of sanctions were as potent as the current ones against Russia.

Furthermore, Switzerland levying sanctions on Moscow represents a huge obstacle to Russia and is a major inflection point for a previously neutral country with significant clout over the financial markets.

The razor-sharp sanctions target deals with Bank Rossii (Russia`s central bank) as well as Russia’s foreign investment fund obstructing Putin from dipping its hands in the kitty it stowed away for years to cushion the predictable sanctions blow-back.

The sanctions impede Russia’s ability to conduct transactions in major currencies and target individual banks and state-owned enterprises.

The sanctions slashed Russia’s access to the American dollar, which, still remains the globally sought after foreign exchange reserve of our international financial system, as its value ascends amid global turmoil.

Without access to its essential reserves, Putin’s government resorted to frantic methods to maintain its fragile financial sector afloat. The Russian central bank increased its baseline interest rate to 20% and restricted any share selling held by international stakeholders to curb the ruble from disintegrating further.

Russia is unable to avert bank runs (as many depositors withdraw money from their accounts), rising inflation and profound economic malaise. Such ramifications will ripple though global markets, including South Asia, further accentuating financial conundrums.

Europe is especially reliant on Russian oil and natural gas exports, which has made European leaders wary of strict economic sanctions on Russia. If Putin responds with limits on Russian energy and food exports, he could force rising prices even higher while reaping the benefits of surging demand.

America and its allies have calculatedly deployed “sanctions of variable geometry” to halt the negative consequences by exempting energy-related payments from the sanctions imposed. Net exporters of energy already witnessed a skyrocketing of natural gas prices, increasing by 40% over the last four quarters.

How South Asia cushions the blow of Western Sanctions on Russia.

A legitimate concern arises, from countries like Pakistan, pertaining to the execution of projects and MoUs signed with Russia while the latter faces tough sanctions and SWIFT bans.

Traders and investment analysts this CQ analyst spoke to anticipate that Russian exports will continue without major disruptions to Pakistan even amid an escalating crisis, whereas Ukrainian exports are more prone to face disruptions. Ukraine is no longer a major transit state for Russia’s gas exports.

Some economists are of the view that the Russia-Ukraine entanglement and sanctions will not majorly dent Pakistan’s growth prospects unless the SBP decides to hike interest rates. Pakistan’s external financing requirements can augment if the international prices of food, energy and other commodities remain alarmingly high over the long-haul.

Pakistan has thus far emerged rather unscathed from the Covid-19 pandemic yet is still painstakingly attempting to grow its economy at a pace and velocity where the economy starts creating new employment opportunities and absorbing around three million new job-seekers entering the market each year.

On the other hand, New Delhi has been walking a tightrope, carefully negotiating its ever-closer relationships with the United States and other Western nations on the one hand and balancing its historically profound strategic ties with Russia on the other.

India is strategically playing both sides, much to the Biden administration’s chagrin. Delhi is yet to criticize Moscow—its deep- seated long-term arms supplier (Russia)—publicly over Ukraine and has instead urged both sides to cease hostilities, causing frustration among its other allies, especially America. How long can India pursue neutrality remains to be seen.

Though India’s top lender, the State Bank of India, as well as a myriad of other lenders, have stopped processing any transactions involving Russian entities subject to international sanctions, India, as officially reported by Reuters, is exploring a Rupee Payment mechanism for trade with Russia to “soften the blow” from sanctions. Empirical simulations conducted in 2021 indicated that EU sanctions on Russia led to greater bilateral trade22 between India and Russia.

India, deeply dependent on Russian fertilizer—especially mineral, chemical and nitrogenous fertilizer—is concerned that essential supplies of fertilizer from Russia could be interrupted as sanctions increase, jeopardizing India’s farming sector, already volatile due to the long farmer’s protests.

Russia and its ally Belarus account for an estimated 33% of India’s total potash imports. It is deemed unfeasible to substitute them during a market rally in fertilizer prices soaring to peak highs.

These realities, along with India’s dependence on Russia`s arms and defence industry, help explain India’s calculated abstention from voting against Russia at the UN recently and refraining from any overt condemnation of Russia or even using the word “aggression” as it still cherishes it`s time-tested military, technology and security links with Moscow.

Indian bankers confirmed that they aspire to get Russian banks and companies to open accounts with a few state-run banks in India for trade settlement23. The banks (may) include the Indian Bank, Bank of Baroda, Union Bank of India, State Bank of India, Canara Bank and more.

Indian financiers reckon that getting Russian companies to open key corporate accounts is a timely maneuver as the Ukraine conflict escalates and a further slew of sanctions are likely.

Indian officials acknowledge that funds deposited in such accounts serve as a payment guarantee for trade between Russia and India, as the states barter commodities from each other to offset the total value.

Another financing mechanism being explored in India is whereby part of the transaction settlement with Russia can be in foreign currency and the remaining amount settled via local rupee accounts. Such a “hybrid settlement model” can be explored by the FBR, SECP, the State Bank of Pakistan and relevant authorities too.

The major difference is that India has more room to financially broker and maneuver deals with Russia as its economy is not under the seemingly never-ending watchful gaze of the Financial Action Task Force, nor is it subject to a restrictive “grey-list” or strict IMF conditionalities as Pakistan is. Islamabad will, therefore, find it tougher to creatively broker deals directly with Russia, as India plans to.

The aforementioned “creative financing” and “hybrid barter models” are usually deployed by nations to shield themselves from the impact of sanctions. In 2012 India also used it with Iran24 (which worked well), after Tehran came under Western sanctions for its nuclear weapons programme, ramping up uranium production towards building an atomic bomb.

To trade with China, Iran also completed projects in Riyals or Chinese Renminbi. (Interestingly in February 2022, Secretary of State Antony Blinken signed waivers permitting foreign states to work on Iran`s civilian nuclear projects like the Arak heavy water plant and Tehran’s Research Reactor).

Indian banks are growing increasingly concerned as trade settlements with Russia stall, owing to Western sanctions. Indian banks are scrambling after bills for imports from Russia bounced and export payments stalled owing to sanctions heaped by the west on Russia.

The Indian Banks’ Association (IBA), an industry association, convened with key bankers on 1 March 2022 to ascertain the impact of Indian-Russian trade disruptions.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) also met with key bankers and financiers and endeavours to evaluate the risk and exposure that lenders have with Russia and Ukraine and the potential impact and credit risk this can pose for Indian banks25. The State Bank of Pakistan will also undertake such due diligence, even though Pakistan`s trade with Russia is much less than India`s, but promises to grow given Moscow`s Eastward foreign policy tilt.

Russian exports to India stood at some $6.9 billion in 2021—mostly fertilizers, pearls, rough diamonds, mineral oils—while India exported $3.33 billion worth of goods—mainly pharmaceutical products, tea and coffee—to Russia in 2021.

In addition, Russia’s exports to India include strategic defense goods. As per the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), an estimated 23 percent of all Russian arms exports between 2016 to 2020 were sent to India, accounting for 49 percent of all Indian arms imports during the same period.

A prime example of Russia’s defence exports to India includes five S-400 regiments in December 2021, with initial deployments along the Indo-Pakistan border. The defensive — and ostensibly offensive — anti- access, area denial abilities of the S-400 are noteworthy. It is interesting to note that when India imported the S-400 American CAATSA sanctions did not apply, whereas when Turkey, a NATO member, sought S-400`s batteries and firing units, CAATSA sanctions applied. This is partly explained by the fact that America selectively and strategically seeks a fully armed India to counterweight China, especially given the border skirmishes, and is willing to look the other way when it comes to applying sanctions.

Of the $53.85 billion spent by India during 2000 to 2020 on arms imports, $35.82 billion went to Russia. During the same period, imports from India’s other major defense trading partners were $4.4 billion from the US and US$ 4.1 billion from Israel26.

Indian Rupee financing for Russian entities is still at a nascent stage. Non-dollar denominated financing models will grow in an increasingly polarized multi-polar world order.

Sino-Russian Alternative Payment Systems – Skirting Western Sanctions

Beijing’s banks decided to financially support Moscow amidst a flurry of sanctions on Russia. Such support can prove vital in shaping the war’s longevity and outcome. Chinese financial succor to Russia amidst sanctions allows Moscow to prolong the war and offers it operational and tactical maneuverability that would otherwise have been lacking.

Beijing is ready to soften the financial blow to Moscow from sanctions. Chinese banks’ economic support for Russia can prove influential in not only determining the invasion’s outcome but devise new ways of thinking about financing models, especially by countries bearing the brunt of FATF grey/blacklists and sanctions.

Guo Shuqing, chairman of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (China`s banking regulator), announced that Chinese banks will not join the sanctions regime against Russia27, whilst cautiously acknowledging that the impact of decided measures on China would be limited. “Overall they will not have much impact (on China), even in the future,” Guo said, citing the resilience of China’s economy and financial sector28.

China has officially termed western sanctions against Russia illegal and unilateral29. China plans on maintaining normal economic and trade ties with Russian entities.

China is ready to throw Russia an economic lifeline (as it extended to Pakistan when KSA were recalling their USD $ 3 billion soft loan from Pakistan) as Putin’s links with the west sever and Moscow suffers snowballing sanctions.

The Financial Times reported30 that China would assist Moscow weather the storm of sanctions, through resource deals and lending by multiple state-owned banks, while simultaneously circumventing damage to its own economic imperatives.

Beijing endeavours to strike a balance between Chinese president Xi Jinping’s support for Putin and China’s self-interest in the wider region’s stability31.

Hua Chunying, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson, refused to categorize Russia’s military maneuvers as an “invasion” and repeated the Russian defence ministry’s talking points. A day before, China rearticulated its stance against “all illegal unilateral sanctions”. Since 2011, America has slapped over one-hundred sanctions on Russia. Beijing asserted that sanctions do not remedy any problem nor will they resolve Ukraine’s conflict.32

The west, at present, is unlikely to exact a measurable cost on China, implying that Beijing will keep helping Russia (especially behind the scenes) as their Eurasian interests converge and also interestingly align with Pakistan’s new National Security Policy, with it’s Eurasian geo- economic slant.

China’s large policy banks, very distinct from its state-backed commercial banks, are anticipated to be key conduits for financial support to Russia. Russia, by far, remains Beijing’s largest loan beneficiary, valued at a whopping USD $151bn between 2000 and 2017, according to AidData, an international research lab. This amount comprises of $86bn in non-concessional and semi-concessional debt from China’s state-owned policy banks and commercial lenders—mostly loans collateralized against future receipts from oil exports33.

Such evolving “Eastern financial models and transactions” can be leveraged by South Asian states, including Pakistan, especially if the FATF retains it on the grey list over the long-term and lenders do not offer realistic concessions to Islamabad.

China Development Bank and the Export-Import (Ex-Im) Bank of China are considered alternatives to the World Bank and the IMF. They are less exposed and dependent to the U.S. dollar system and therefore have more options to finance transactions in uniquely innovative manners which are less susceptible to sanctions34.

Chinese commercial banks will still be highly cautious of the credit risk impact such deals could pose on their operations in global markets and their access to the US dollar system. However, the main lending and borrowing activities of Chinese policy banks, are rooted in the “global south”. Therefore, they are less concerned about being hit for abrogating US sanctions. China will, therefore, likely lend money to Russia following the “state-to-state sanctions-proof model.”35 Such a lending formula can equally extend to China’s key CEPC ally, Pakistan.

The western bloc unanimously decided to exclude Russian banks from the SWIFT financial messaging system. This will likely hasten an increased use and expansion of Russia’s SWIFT equivalent known as Sistema peredachi finansovykh or SPFS (System for Transfer of Financial messages) by the country’s Central Bank.

In 2014, after the invasion of Crimea, the Central Bank of Russia created its own proprietary financial messaging system termed the System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS). As of 2020, SPFS had over 400 registered financial institutions. Unlike the SWIFT which works 24/7, SPFS operations are conducted during working hours. The system also limits the size of messages to 20 kilobytes. All this could change given Russia`s altered global status post-Ukraine incursion.

In addition, SWIFT banning Russia is likely to also accelerate the adoption of Beijing’s cross-border payment and settlement system, known as the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS)— Beijing’s retort to America’s dollar-denominated SWIFT financial messaging system. CIPS was initiated in 2015 to enhance global use of China’s currency in trade settlements.

India is also likely to promote its own equivalent, known as the Structured Financial Messaging System or SFMS, especially in South Asia and in the Indo-Pacific.

With Russian projects with Pakistan and other South Asian states (especially India—heavily reliant on Russian trade) getting invariably delayed due to SWIFT banning, the alternative SPFS, SFMS and CIPS are likely to be adopted (if necessary), adding to South Asian financial independence and greater autonomy in terms of Eurasian project completions, countering sanctions, money transfers and energy/food security.

Moscow’s SPFS and Shanghai based CIPS are also likely to increase in influence in light of a seismic global geopolitical realignment from west to east, where Russia and China increasingly hold geo-strategic sway. This will promote their financial money clearing systems to complement their rising political heft and global projects.

SPFS36 and CIPS offer Moscow and Beijing greater financial latitude and autonomy for independent global yuan and ruble payments and clearing systems linking onshore and offshore37 clearing markets and participating banks.

Shanghai’s CIPS employs more than 100 people and has registered capital worth 2.38 billion yuan (US$376.9 million)38. The financial infrastructure is overseen by the People’s Bank of China.

The China National Clearing Centre, an affiliate of the People’s Bank of China (central bank), is the largest shareholder, with a stake of 15.7 per cent. The National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors, the Shanghai Gold Exchange, China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation and China Union Pay, each own 7.85 per cent shares39.

Russia’s SPFS or China’s CIPS or India’s SFMS were architected to bolster global use of Russian Rubles, Chinese Renminbi and Indian Rupees, not only to enhance and project their domestic currencies but to ensure trade settlements that circumvent ubiquitous sanctions regimes that delay essential projects.

The Chinese media stated that CIPS could work alongside SPFS to counter western SWIFT restrictions. Media outlets Xinhua and the Communist Youth League Central Committee’s website quoted Chinese researchers as saying that the two systems combined would eventually gain clout and mature into an essential global interbank payment system.

Dong Xiaopeng, the deputy editor-in-chief of China’s Securities Daily, said that the SWIFT ban does not preclude Russia from continuing international trade and clearance, but essentially makes SPFS or CIPS more viable and potent as a new alternative.40

Global financiers pre-emptively indicate that sanctions on Russian banks are an early warning wake-up call for Beijing. As viewed from Russia’s SWIFT exclusion and given the intense China-US trade wars in recent years, Beijing and Moscow will, by course of necessity, reduce their reliance on SWIFT to ensure financial autonomy and security.

The integration between international financial institutions and China’s CIPS will be given a fillip in an increasingly polarized world order.

Such alternative “Eurasian” trading and financial settlement systems gain prominence in lieu of ambitious cross-border initiatives such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative, incorporating hundreds of billions of yuan worth of Chinese investment globally as well as Russian mandates like the EAEU (Eurasian Economic Union)41, aiming to stimulate deeper Eurasian economic cooperation and integration. This is aligned with Vladimir Putin’s proposed Greater Eurasian Partnership (GEP), seeking to streamline and consolidate economic, energy (hydrocarbons)42 and infrastructure integration projects from Vladivostok to Lisbon.

Use of the Chinese yuan increased after its inclusion in the International Monetary Fund’s Special Drawing Rights43 basket in 201544. Yet, its present share is not in equal proportion with its status as the world’s second largest economy, accounting for 18 per cent of global gross domestic product.

SWIFT data confirmed that the Chinese yuan accounted for only 3.2 per cent of global payments in January 2022, still way beneath the US dollar, which accounted for 39.92 per cent of global settlements. The Euro accounted for 36.56 per cent and the British pound, 6.3 per cent45.

CIPS, however significantly grows. It reported 2.68 million transactions in the first 11 months of 202146, an increase of 58 per cent from 2020. The transaction value catapulted by 83 per cent to 64 trillion yuan, the Shanghai Securities News reported.

After CIPS launched in 2015, 19 prominent banks signed on to phase one of the project. These included eleven Chinese banks and eight locally registered entities of overseas banks with a roster of brand names such as Standard Chartered, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Citi Bank, DBS Bank, Bank of East Asia, BNP Paribas and ANZ47.

In January 2021, CIPS boasted 1,280 users spread across 103 countries, including 75 directly participating banks and 1,205 indirect participants. The operator confirmed that overseas indirect participants account for 54.5 per cent of the total.

The involvement of huge global bank branches sets CIPS apart from Russia’s System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS), which has around 400 users but only a dozen foreign banks from countries such as China, Cuba, Belarus, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan.

Shanghai’s CIPS is much smaller than SWIFT, utilized by 11,000 financial institutions across 200 countries or regions, including nearly 600 Chinese banks.

At present, there is more cooperation as opposed to competition between the two systems. SWIFT set up a wholly-owned subsidiary in Beijing in 2019, while also forging a joint venture with several affiliates of the Chinese central bank (As well as CIPS)in early 2021. Though Chinese Yuan digital wallets swell in numbers, usage lags.

As nearly 40 percent of the world’s international claims are still settled in dollars, CIPS, whose share is a mere 3 percent, still has a long way to travel and is not (as yet) a challenge for U.S. CHIPS.

According to SWIFT’s own data, the platform moves 50 million messages a day. CIPS does only 15,000. SWIFT’s messages enable transactions worth $5 trillion across the world each day. CIPS has 1,205 indirect participants and 75 direct participants, while SWIFT has 11,000 members.

Obviously the CIPS and SPFS systems are significantly smaller than SWIFT in terms of participants and users, however, over the long haul, it is likely that together or one of them (most likely CIPS) will grow into an important regional and even international payment settlements and infrastructure system with rising influence.

Since Crimea’s annexation in 2014, China and Russia have both lowered the usage of the dollar in their mutual trade. Sino-Russian financial rapport grows. Bilateral trade hit a record high of more than $145 bn in 2021.

Russian initiatives to take the sting out of sanctions by boosting settlements in other (non-U.S. dollar) currencies was reflected in a spate of recent energy transactions with China. These provisions skirted the dollar-denominated financial sector with loans and credit in Chinese Renminbi. If push comes to shove, South Asian countries may mirror similar trade and transaction terms.

In late February 2022, Gazprom Neft declared that it was switching all settlement for fueling Russian planes in China to Renminbi48, the very first Russian company to do so. This is a trend likely to carry on in the months and years to come.

When Putin met Xi in Beijing in February 2022, Russia’s Gazprom and China’s National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) signed a 25-year deal on a new gas supply route, the Power of Siberia pipeline, which is anticipated to reach full capacity in 2025.

In February 2022, Rosneft—Russia’s top crude producer and its top oil exporter to China, representing 7 per cent of the country’s total annual demand—agreed with CNPC to supply 100 million tonnes of oil to China through Kazakhstan49 over ten years. The crude oil will be processed at factories in northwest China.

Moscow and Beijing are also working on a third gas pipeline project through Mongolia. Analysts believe that a deal could be inked by the end of 2022.

Despite the substantive aforementioned deals, a sizeable portion of Russian trade is still rooted in the age-old time-tested dollar system.

As per the Russian Central Bank data, in the initial nine months of 2021, Russia and China conducted 8.7 per cent of their trade in Russian Rubles and 7.1 per cent in a basket of alternative currencies. Dollars and Euros accounted for 36.6 per cent and 47.6 per cent of Russia-China trade, respectively.

The US will also deploy export controls to cut off computer chip supplies to Russia. That strike could cripple Russia’s supply of technology components essential for industries ranging from telecoms to oil exploration. Washington and European capitals, as well as Taiwan, are preparing an inventory of likely products to fall under export controls, including “military and dual-use products, essential infrastructure, technology and strategic supplies.”50

Chinese and Russian rapprochement, on the other hand, has intensified. As per Chinese customs data, Cumulative trade between the two increased by 35.9% in 2021, a trail-blazing $146.9 billion51. Russia supplied gas, oil, coal and agriculture commodities, enjoying a trade surplus with China.

China’s prime exports to Russia include multi-media broadcasting equipment ($4.1 billion), computers and laptops ($2.13 billion), and automotive parts ($1 billion).

Russia keenly eyes China’s gigantic demand for wheat, sunflower vegetable oil and other commodities. China could become a major buyer of Russian wheat and sunflower oil to offset extensive financial sanctions jeopardizing Russia’s agriculture trade flows to its traditional European markets.

Beijing’s intensifying agriculture trade relation with Moscow was emphasized through the endorsement of a wide-ranging wheat import agreement signed on 24 February 2022. Under this agreement Russia is permitted to sell wheat from all its regions and use its deep seaports to ship them, competing with other wheat exporters eyeing Chinese markets.

Previously, China imported sunflower oil from Ukraine. A protracted skirmish will position Russia as a potential sunflower oil supplier to China, since presently many Russian ports remain operational in the Black Sea region, whereas Ukrainian ports and railways remain shut52. Shipping giant Maersk ceased port calls in Ukraine and sealed its Odessa office on the Black Sea due to the conflict.

Light at the end of the tunnel?

Pakistan presented a three-point formula to solve the Russia Ukraine crisis. Munir Akram, Pakistan’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, said, “If we take a one-sided position, then we have no room for diplomacy.” In his address at an emergency special session of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) he communicated that: “Three steps should be taken to end the war: ceasefire, negotiation, and implementation of previous agreements.”53

Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi spoke to Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba and reiterated Islamabad’s “serious concern at the situation, underscoring the importance of de- escalation, dialogue and stressing the indispensability of diplomacy.”54

Due to national interests and compulsions, China, India and Pakistan, as well as most of South Asia, abstained from voting in the resolution on Russia at the UN.

Pakistan is of the view that the Ukraine issue must be resolved through the UN charter, international law. This has already been conveyed to Vladimir Putin by Prime Minister Imran Khan during his recent meeting in Moscow.

Pakistan remains committed to the fundamental principles of the UN Charter, self-determination of peoples, non-use or threat of use of force, sovereignty and territorial integrity of states, and pacific settlement of disputes. Pakistan upholds the principle of equal and indivisible security for all. On the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Pakistan consistently emphasized the need for de-escalation, renewed negotiations, sustained dialogue, and continuous diplomacy55.

President Putin, however, remains unambiguous in his desire to usher regime change in Kiev prior to ending his military campaign. This will be tenuous if previous political conflagrations in Ukrainian politics act as a roadmap. Given the sharp divide amongst the Russian and Ukrainian population within Ukraine itself, maintaining law and order in that fragile state will remain a delicate conundrum for all hues of present and future Ukrainian leaders. With a majority Russian population, eastern Ukraine acts as a strategic reserve for Russia.

If Ukraine becomes a long-term apple of discord between Moscow and Washington, then it will likely linger for decades, hampering prospects of peace in Russia, Eurasia and the West. It could also embolden China to flex its muscles in the Indo-Pacific and South China Sea. Further, civil war or break up of Ukraine would herald a balkanization of several other neighbouring states in the Eastern European bloc, which would remain mired in division and polarization.

In Moscow’s calculation, the West can do little beyond sanctions and hyperbole since its refusal to commit boots on the ground. Ultimately, NATO’s restraints, the Kremlin’s agenda, Ukraine’s resistance, and negotiation skills will cumulatively determine the outcome, not Western sanctions. For Russia, the new security engineering premised on Ukraine’s neutrality, is a deciding factor.

Therefore, a totally neutral Ukraine serves the combined interests of Europe, the U.S and Russia. Here NATO too must exercise restraint, especially in terms of expansion. A neutral non-NATO allied Ukraine is the meaningful way forward. Using Ukraine, as is currently the case, as a pawn in the broader chessboard of regional realpolitik is untenable over the long-haul.

Selected Bibliography and Citations

Guduru, Kavya (2021) JP Morgan sees oil prices hitting $125 in 2022, $150/bbl in 2023, Nasdaq, 2 December, 2021.

Garda Alerts (2022) https://crisis24.garda.com/alerts/2022/02/pakistan-pakistan-peoples-party-ppp-to-start-opposition-march-towards-islamabad-from-karachi-feb-27

Quarterly Report on IMF Finances For the Quarter Ended January 31, 2021. International Monetary Fund, 31 January, 2021.

DW (2022) IMF approves 1 billion loan for Pakistan at https://www.dw.com/en/imf-approves-1-billion-loan-for-pakistan-reviving-bailout-package/a-60642372

Nasir, Jamal (2022) Ukraine crisis fall-out fears, Dawn, 21 February, 2022.

Russia-Ukraine Crisis to hurt Pakistan`s Current Account (2022) Dawn, 15 February, 2022.

Khurshid, Ahmed (2022) Pakistan to implement new set of IMF conditions under $6 billion loan program, Arab News, February 6, 2022.

The News International (2021) Cheaper LNG deal inked with Qatar at https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/796105-cheaper-lng-deal-inked-with-qatar

Energy challenge (2022) Dawn, March 1, 2022

Lane, Sylvan and Gangitano, Alex (2022) Unprecedented Western sanctions struggling Western economy, The Hill, 28 February, 2022.

World Population Review (2022) Countries by national debt at https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/countries-by-national-debt

Singh, Mayengbam Lalit, and Chingshubam Manimohon Singh (2021) “Has EU’s Sanctions on Russia Led to Greater Bilateral Trade between India and Russia? A Simulation Analysis.” FOCUS: Journal of International Business 8.2 (2021): pp. 111-130.

Susan Ullas, Sruthy (2022) “Ukraine crisis: Indian student killed during shelling in Kharkiv”. The Times of India. 1 March, 2022.

Cheng, Evelyn (2022) China will not join sanctions against Russia, banking regulator says, CNBC, 2 March, 2022.

Yao, Kevin (2022) China will not join sanctions on Russia banking regulator says,

Reuters, March 2, 2022.

Wang, Orange (2022) China opposes ‘illegal’ sanctions against Russia by United States and its allies, SCMP, 2 March, 2022.

Seddon, Maz, Astrasheuskaya, Nastassia and Maiqi Ding (2022) China ready to soften economic blow to Russia from Ukraine sanctions, Financial Times, February 24, 2022.

Rafferty, Tom (2022) Russia-Ukraine Crisis, The Economist Intelligence Unit, South China Morning Post. February, 23, 2022.

White, Edward and Kathrin Hille (2022) China ready to soften economic blow to

Russia from Ukraine sanctions, Financial Times, February 24, 2022.

Masood, Salman (2022) Pakistan Will Cut Energy Prices to Offset Rising Costs After Invasion, New York Times, 28 February, 2022.

Financial Times (2021) at https://www.ft.com/content/fb64d5f8-ed3e-4b1f-aab4-d19927519efe on 29 December, 2021.

The News (2022) at https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/934321-no-let-up-in-gas-crisis-lng-firms-renege-on-commitment-to-provide-cargoes

S & P Global (2022) Qatar takes center stage in LNG market as buyers seek supply at https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/market-insights/latest-news/natural-gas/020422-feature-qatar-takes-center-stage-in-lng-market-as-buyers-seek-supplies

Group Atradius (2021) Russia fortress strategy is not for free https://group.atradius.com/publications/economic-research/russia-fortress-strategy-is-not-for-free.html

Central Bank squeeze lacks energy to cripple Russia`s economy (2022) Wall Street Journal at https://www.wsj.com/articles/central-bank-squeeze-lacks-energy-to-cripple-russias-economy-11646062881

Nicholas, Gordon (2022) Banks are stopping Putin from tapping a $630 billion war chest Russia stockpiled before invading Ukraine, Fortune, March 3, 2022.

https://fortune.com/2022/03/03/russia-sanctions-central-bank-ruble-us-eu-foreign-reserves/

Reuters (2022) India Explores Rupee Payment Mechanism For Trade With Russia To Soften Sanctions Blow. 25 February, 2022.

The Iran and Libya Sanctions Act (ILSA) signed on 5 August 1996 (H.R. 3107, P.L. 104–172).

Anand, Nupur (2022) Indian banks concerned as trade settlements with Russia stall in face of sanctions, March 2, 2022.

India Russia Military Weapons Defense Ties (2021) Indian Express at https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/india-russia-military-weapons-defence-ties-7795804/

Access Russia`s SPFS payment and clearing system at http://www.cbr.ru/psystem/fin_msg_transfer_system/

Reuters (2022) “Factbox: What is China’s onshore yuan clearing and settlement system CIPS?”. Reuters. 28 February, 2022.

CIPS shareholders (2022) according to business registration information published by Tianyancha.com.

Russia Ukraine war can CIPS China`s potential Swift competitor help Russia (2022) CNBC Tv 18 at https://www.cnbctv18.com/world/russiaukraine-warcan-cips-chinas-potential-swift-competitor-help-russia-12673332.htm

Farchy, Jack (2014) “Eurasian unity under strain even as bloc expands”. The Financial Times. 23 December, 2014.

Mukhtarov, Daniyar (2014) “Single hydrocarbons market of Eurasian Economic Union to be created by 2025” 24 May, 2014.

The Economist (2020. “Special delivery: Should the IMF dole out more special drawing rights?”. The Economist, 11 April, 2020

Kevin P. Gallagher, José Antonio Ocampo, and Ulrich Volz. (2021) “IMF Special Drawing Rights: A key tool for attacking a COVID-19 financial fallout in developing countries”. Brookings Institution, 26 March, 2021.

“IMF Launches New SDR Basket Including Chinese Renminbi, Determines New Currency Amounts” (2016) IMF. September 30, 2016.

Jing, Shi (2022) Yuan rising in global payments, China Daily, February 18, 2022.

Borst, Nicholas (2016) CIPS and the International Role of the Renminbi, Federal Reserve bank of San Francisco, 27 January, 2016.

Tang, Frank (2022) What is China’s Swift equivalent and could it help Beijing reduce reliance on the US dollar? South China Morning Post, 25 February, 2022.

Parsakova, Tsvetana (2021) Gazprom Neft Switches To Yuan Payments In China, Oil Price, 6 September, 2021.

Tass News Agency (2022) Rosneft, CNPC agree on supply of 100 mln tonnes of oil through Kazakhstan in 10 years, Tass, 4 February, 2022.

White, Edward and Hille, Katherine (2022) China ready to soften economic blow to Russia from Ukraine sanctions, Financial Times, 24 February, 2022.

Qiu, Stella and Tony Munroe (2022) China Russia trade has surged as countries grow closer, Reuters, 1 March, 2022.

Shashwat, Pradhan (2022) A look at Russia-China wheat sunflower oil trade as Ukraine crisis rages, s & p Global, Commodity Insights, 2 March, 2022.

Pakistan presents three-point formula to solve Ukraine crisis (2022) The News International, Jang Group, 3 March, 2022.

Qureshi underscores de-escalation in talks with Ukrainian counterpart at https:// www.thenews.com.pk/print/937409-qureshi-underscores-de-escalation-in-talks-with-ukrainian-counterpart 28 February, The News, 2022.

References

- https://crisis24.garda.com/alerts/2022/02/pakistan-pakistan-peoples-party-ppp-to-start-opposition-march-towards-islamabad-from-karachi-feb-27

- Quarterly Report on IMF Finances For the Quarter Ended January 31, 2021. International Monetary Fund, 31 january, 2021.

- https://www.dw.com/en/imf-approves-1-billion-loan-for-pakistan-reviving-bailout-package/a-60642372

- Masood, Salman (2022) Pakistan Will Cut Energy Prices to Offset Rising Costs After Invasion, New York Times, 28 February,

- https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/jp-morgan-sees-oil-prices-hitting-125-2022-150bbl-2023-2021-12-02/

- BBL stands for a billion barrels of petroleum liquids. It refers to a barrel of crude oil.

- Guduru, Kavya (2021) JP Morgan sees oil prices hitting $125 in 2022, $150/bbl in 2023, Nasdaq, 2 December, 2021.

- Jamal, Nasir (2022) Ukraine crisis fall-out fears, Dawn, 21 February, 2022.

- Russia-Ukraine Crisis to hurt Pakistan`s Current Account (2022) Dawn, 15 February 2022.

- Financial Times (2021) at https://www.ft.com/content/fb64d5f8-ed3e-4b1f-aab4-d19927519efe on 29 December,

- Khurshid, Ahmed (2022) Pakistan to implement new set of IMF conditions under $6 billion loan program, Arab News, February 6, 2022.

- https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/934321-no-let-up-in-gas-crisis-lng-firenege-on-commitment-to-provide-cargoes

- Energy challenge (2022) Dawn, March 1, 2022

- The News International (2021) Cheaper LNG deal inked with Qatar at https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/796105-cheaper-lng-deal-inked-with-qatar

- S & P Global (2022) Qatar takes center stage in LNG market as buyers seek supply at https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/market-insights/latest-news/natural-gas/020422-feature-qatar-takes-center-stage-in-lng-market-as-buyers-seek-supplies

- Energy challenge (2022) Dawn, March 1, 2022

- https://group.atradius.com/publications/economic-research/russia-fortress-strategy-is-not-for-free.html

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/central-bank-squeeze-lacks-energy-to-cripple-russias-economy-11646062881

- Nicholas, Gordon (2022) Banks are stopping Putin from tapping a $630 billion war chest Russia stockpiled before invading Ukraine, Fortune, March 3, 2022.

- https://fortune.com/2022/03/03/russia-sanctions-central-bank-ruble-us-eu-foreign-reserves/

- Lane, Sylvan and Gangitano, Alex (2022) Unprecedented Western sanctions struggling Western economy, The Hill, 28 February, 2022.

- Singh, Mayengbam Lalit, and Chingshubam Manimohon Singh (2021) “Has EU’s Sanctions on Russia Led to Greater Bilateral Trade between India and Russia? A Simulation Analysis.” FOCUS: Journal of International Business 8.2 (2021): pp. 111-130

- Reuters (2022) India Explores Rupee Payment Mechanism For Trade With Russia To Soften Sanctions Blow. 25 February, 2022.

- For more on S. sanctions against Iran consult: The Iran and Libya Sanctions Act (ILSA) signed on 5 August 1996 (H.R. 3107, P.L. 104–172).

- Anand, Nupur (2022) Indian banks concerned as trade settlements with Russia stall in face of sanctions, March 2, 2022.

- https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/india-russia-military-weapons-defence-ties-7795804/

- Cheng, Evelyn (2022) China will not join sanctions against Russia, banking regulator says, CNBC, 2 March, 2022.

- Yao, Kevin (2022) China will not join sanctions on Russia banking regulator says, Reuters, March 2, 2022.

- Wang, Orange (2022) China opposes ‘illegal’ sanctions against Russia by United States and its allies, SCMP, 2 March, 2022.

- Seddon, Maz, Astrasheuskaya, Nastassia and Maiqi Ding (2022) China ready to soften economic blow to Russia from Ukraine sanctions, Financial Times, February 24, 2022.

- Rafferty, Tom (2022) Russia-Ukraine Crisis, The Economist Intelligence Unit, South China Morning Post. February, 23, 2022.

- White, Edward and Kathrin Hille (2022) China ready to soften economic blow to Russia from Ukraine sanctions, Financial Times, February 24, 2022.

- Seddon, Maz, Astrasheuskaya, Nastassia and Maiqi Ding (2022) China ready to soften economic blow to Russia from Ukraine sanctions, Financial Times, February 24, 2022.

- Rafferty, Tom (2022) Russia-Ukraine Crisis, The Economist Intelligence Unit, South China Morning Post. February, 23, 2022.

- White, Edward and Kathrin Hille (2022) China ready to soften economic blow to Russia from Ukraine sanctions, Financial Times, February 24, 2022.

- Access Russia`s SPFS payment and clearing system at www.cbr.ru/psystem/fin_msg_transfer_system/

- Tang, Frank (2022) What is China’s Swift equivalent and could it help Beijing reduce reliance on the US dollar? South China Morning Post, 25 February, 2022.

- Reuters (2022) “Factbox: What is China’s onshore yuan clearing and settlement system CIPS?”. Reuters. 28 February, 2022.

- CIPS shareholders (2022) according to business registration information published by Tianyancha.com.

- https://www.cnbctv18.com/world/russiaukraine-warcan-cips-chinas-potential-swift-competitor-help-russia-12673332.htm

- Farchy, Jack (2014) “Eurasian unity under strain even as bloc expands”. The Financial Times. 23 December, 2014

- Mukhtarov, Daniyar (2014) “Single hydrocarbons market of Eurasian Economic Union to be created by 2025” 24 May, 2014.

- Special drawing rights (SDRs) are supplementary foreign exchange reserves held by the IMF. SDRs are units of account, representing a claim to currency held by IMF member countries for which they may be exchanged. For more: The Economist (2020. “Special delivery: Should the IMF dole out more special drawing rights?”. The Economist, 11 April, 2020 and Kevin P. Gallagher, José Antonio Ocampo, and Ulrich Volz. (2021) “IMF Special Drawing Rights: A key tool for attacking a COVID-19 financial fallout in developing countries”. Brookings Institution, 26 March, 2021

- “IMF Launches New SDR Basket Including Chinese Renminbi, Determines New Currency Amounts” (2016) IMF. September 30, 2016.

- Jing, Shi (2022) Yuan rising in global payments, China Daily, February 18, 2022.

- Reuters (2022) “Factbox: What is China’s onshore yuan clearing and settlement system CIPS?”. Reuters. 28 February, 2022.

- Borst, Nicholas (2016) CIPS and the International Role of the Renminbi, Federal Reserve bank of San Francisco, 27 January, 2016.

- Parsakova, Tsvetana (2021) Gazprom Neft Switches To Yuan Payments In China, Oil Price, 6 September, 2021.

- Tass News Agency (2022) Rosneft, CNPC agree on supply of 100 mln tonnes of oil through Kazakhstan in 10 years, Tass, 4 February, 2022.

- White, Edward and Hille, Katherine (2022) China ready to soften economic blow to Russia from Ukraine sanctions, Financial Times, 24 February, 2022.

- Qiu, Stella and Tony Munroe (2022) China Russia trade has surged as countries grow closer, Reuters, 1 March, 2022.

- Shashwat, Pradhan (2022) A look at Russia-China wheat sunflower oil trade as Ukraine crisis rages, s & p Global, Commodity Insights, 2 March, 2022.

- Pakistan presents three-point formula to solve Ukraine crisis (2022) The News International, Jang Group, 3 March, 2022.

- Qureshi underscores de-escalation in talks with Ukrainian counterpart at https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/937409-qureshi-underscores-de-escalation-in-talks-with-ukrainian-counterpart 28 February, The News, 2022.

- Pakistan presents three-point formula to solve Ukraine crisis (2022) The News International, Jang Group, 3 March, 2022.