by Ozer Khalid*†

*The author is a geo-strategist, a senior management consultant, a development sector director and an international journalist. Twitter follow @ozerkhalid and e-mail [email protected]

†Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein are a collation of thoroughly researched empirical and expert views, and neither necessary reflect the author`s nor Criterion Quarterly`s editorial stance.

Abstract

(Discerning Criterion Quarterly readers, fasten your seatbelts and brace yourselves for the bellicose advent of what this analyst terms ISIS 2.0 which sees ISIS now evolve into a looser fragmented network of trans-national terror

moving from a physical place to fight in toward an idea to die for. The latter being more sinister, potent and insidious. Fluid and asymmetric in tactical maneuvering, relying on “freelance lone offenders” and a “Cyber Caliphate”, this is ISIS 2.0. – Author)

A Halloween from Hell

On October 31, 2017, as a rented truck ruthlessly rammed into cyclists and pedestrians, leaving at least 8 civilians dead and 12 injured, “Manhattanites” witnessed what seemed to be a haunting Halloween prank only to discover that this was real-life terror unfolding before their unbelieving eyes.

The location of the terrorist attack was symbolic and strategically chosen: a stone`s throw away from the World Trade Center Memorial, giving the “Big Apple`s” resilient residents an eerie spectacle of déjà vu. The perpetrator has been identified as Uzbek immigrant Sayfullo Saipov, 1 who confessed to being ISIS inspired, which is likely to stimulate many more “copy-cat” attacks in 2018 and beyond.

With the precipitous fall of Mosul and Raqqa, ISIS` territorial cookie crumbles, degrading them from a “proto-state” to an “insurgency” which is all the more fluid, deceptive and asymmetric 2 in maneuverability, making them a more insidious menace to monitor and capture. To compensate for territorial losses in their hinterland of Iraq and Syria, IS will, from afar, keep conducting such “remote-controlled” face-saving atrocities to remain relevant.

Territoriality vanquished, IS, have momentarily reconciled themselves to a “Cyber Caliphate” to digitally incite hatred, drive engagement, bolster recruitment and what this author dubs freelance terrorism or home-grown nihilistic “lone wolf attacks” 3. Welcome to the insidious advent of ISIS 2.0.

Such digital tactics are proving horridly useful. Saipov, the Lower Manhattan attack perpetrator, notified the police that he purposely chose Halloween to target maximum civilians. Saipov stated that he was especially touched after watching Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi`s video questioning the American Muslim response to Muslims killed in Iraq. Investigators found other IS streaming and content on his electronic devices. This sick depraved individual even requested to display the ISIL flag in his hospital room and stated that he “felt good” about what he had done.

The headline-hungry IS death cult will claim any attack they can (even when not their own), as the recent Las Vegas shooting attests. IS, through online propaganda will brain-wash currently returning fighters, who will sneakily camouflage themselves as refugees, snaking their sinister way into Western nations, laying low till the dust settles, before striking again when the iron sears hot. Tactically speaking, IS now decrees aspiring militants to mount increasing attacks using everyday items like knives, acid 4 and vehicles.

Manhattan`s vehicular assault mirrors the Nice Bastille Day 5, Barcelona, Berlin Christmas Market and London`s Westminster Bridge attacks 6, all being ISIS triggered vehicular attacks ordained by IS head-quarters. IS are now hell-bent upon unleashing terror in the West, which they term as Rumiyah, a nauseating reference to the Christian Roman empire of yore, to unleash terror upon infidel “Crusaders”.

Halloween`s Manhattan attack reveals that militarily vanquishing IS in Syria and Iraq does not suffice; the main challenge remains an ideological one, which cannot be curtailed by kinetics but rather by delegitimizing the ideology.

Our reaction to such attacks must be calculatedly discerning and not knee-jerk reactionary. Our world is dangerously teetering on a hotbed of hate speech. Military stealth is at best a momentary stepping stone, and at worst a superficial victory indicator, never a substantive long-term action plan. The U.S. has already spent a heaving USD $ 6 trillion on the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) (a vertiginous USD $ 23,000 per U.S. tax payer) since 9/11, yet terrorist attacks keep surging the world over, blind-folding the U.S. in the face of a so-called 7 Global Jihadist insurgency. The U.S. will spend US $ 1.2 trillion on upgrading its nuclear capabilities in 2018 yet “home-grown” attacks are proliferating in the very heart (New York) of the “free world”.

Terrorism is like Nosferatu 8, in that no matter what authorities seemingly do, it just never dies, merely mutates and metastasizes. In the absence of any striking counter ideology, terrorism has become the counter-culture, the zeitgeist du jour, the movement du moment.

To make things worse, the world in general, and the U.S. in particular, are more racially, ethnically and religiously polarized than ever before. Charlottesville, Ferguson, San Bernardino and Orlando vividly exemplify this. Racists promptly jump onto the Islamophobia bandwagon claiming that the Manhattan terrorist proclaimed Allah-hu-Akbar (God is Great) before unleashing hell in Manhattan. Every devout Muslim utters “God is Great” during prayers. Prosecute the crime. Never the faith.

The Manhattan attack should not become a predictable scapegoat to parade religious bigotry and exclusionary identity politics which have alarmingly risen. The U.S. is home to 3 million Muslims, and Europe hosts 26 million, these citizens are the essential “eyes and ears” of the community and should not be alienated as it ferments venal extremism.

As IS now evolves from a “physical place” to fight in toward an “ideological idea” to die for. Non-military intellectual capital is needed to counter radicalize because ideas are bullet-proof. Insidious ideas are ultimately only countered by better ones, by nurturing religious tolerance, offering minorities a true feeling of freedom, especially a freedom to practice and peacefully profess their own faith along with a carefully co-ordinated deradicalization program of IS` returning fighters, especially stateless widows and children, under the auspices of the UN and international donors.

Social inclusion, counter-narratives, positive Muslim role models for an alienated youth to look up to, civil society push-back, education and grass-roots momentum are the way forward.

Now, the intellectual challenge against extremism is the real “ideological war after the physical war”. It requires the international community to evolve from solely deploying “hard power” of military might towards exploring the suasion of “soft power” 9.

By course of necessity, deploying “soft power” in counter radicalization involves sensitization, rehabilitation, education, refugee repatriation and inter-faith bridge-building.

The Advent of ISIS 2.0

An inflammatory civil war in Syria rages to date, destabilizing the entire region with hideous spill-over effects. Radicalization is culturally and conceptually embedded within the veins of an increasingly disenfranchised population in Iraq and Syria.

In 2014 this power vacuum gave incestuous birth to ISIS, which in October 2017, territorially speaking, encounters irreversible demise, especially in their hinterland of Iraq and Syria, losing precious land, momentum, human-power and operational capabilities. Such defeat is a watershed against IS but it scarcely represents the “Waterloo” which coalition forces envisaged.

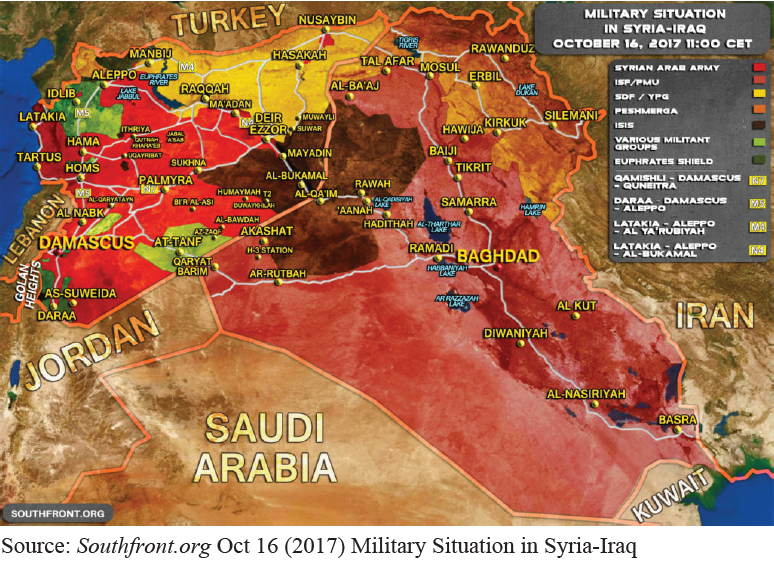

The forces of time, space and geography coalesce against IS. For now IS` faux-Caliphate and their looming apocalyptic narrative is physically (yet not conceptually) undermined. ISIS have lost territory conquered, resources captured and fighters recruited which inevitably tames their expansionist zeal. Final nails are being hammered into IS` territorial coffin with the liberation of Raqqa 10 11 and Mosul from IS` tyrannical grip as the images hereunder illustrate.

The forces of time, space and geography coalesce against IS. For now IS` faux-Caliphate and their looming apocalyptic narrative is physically (yet not conceptually) undermined. ISIS have lost territory conquered, resources captured and fighters recruited which inevitably tames their expansionist zeal. Final nails are being hammered into IS` territorial coffin with the liberation of Raqqa 10 11 and Mosul from IS` tyrannical grip as the images hereunder illustrate.

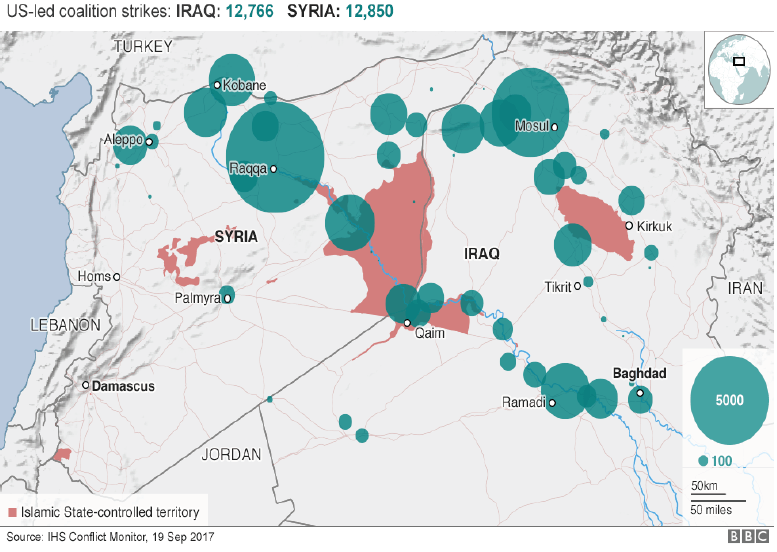

In addition to the coalition`s aerial assaults, Kurdish forces, SDF ground attacks, a leadership vacuum (when rumors ran rife that al-Baghdadi breathed his last), internal dissent among their ranks and other factors catalyzing IS`s demise. IS`s Faruq al-Masri, 12 their War Minister, who disagreed with Senior IS members on their Manhaj (strategic direction) also voiced concern that IS should not have been so trigger-happy to declare so many Wilayats (Provinces). Al-Masri also conceptually stated that pledges of allegiance to IS should have been undertaken more discretely. Dissent was also rife amongst IS`s Yemen affiliates. Internally, IS became less of a “monolith” and more of a fractious and fractured “mosaic”.

In 2014, when IS evolved from an insurgency to a full-fledged state, it lost many competitive advantages it once enjoyed (which it will devastatingly regain in 2018). As a fixed proto-state, with a Weberian monopoly over the use of force within it`s territories, IS had to shoulder the necessary responsibilities that accompany governance, from conferring ample resources to securing cities and offering essential services. By becoming physically bound to specific locations, IS opened itself up to years of punitive airstrikes. Russian, U.S. and Alliance led coalition bombing assaults, commencing in August 2014, meaningfully degraded IS` military prowess by destroying a considerable amount of its equipment and troops.

Even in its core territory in Syria and Iraq, IS struggled to conquer areas with Sunni majorities and into Shiite and Kurdish communities. Growth stymied, IS lost Manbij, a crucial smuggling/human traficking route and a strategic gateway to Turkey. IS was defeated in Mosul, a financial haven. They were vanquished in the prophetically significant town of Dabiq in northern Syria and have now been dealt a definitive blow in their symbolic capital of Raqqa.

Cautious optimism is warranted, for even though ISIS has momentarily been `defeated` they are now dangerously `dispersed`, rendering them tougher to trace, monitor and pin down. ISIS might be down but they are certainly not out, as this author observed in Criterion Quarterly`s Volume 12, No.3 July-September, 2017 edition 13. The ecosystem of civilization`s enemy (IS) remains.

Discerning Criterion Quarterly readers, fasten your seatbelts and brace yourselves for the bellicose advent of what this analyst terms ISIS 2.0 which sees ISIS now evolve into a looser fragmented network of trans-national terror, moving from a physical place to fight in toward an idea to die for. The latter being more sinister, potent and insidious. Fluid and asymmetric in tactical maneuvering, relying on “freelance lone offenders” and a “Cyber Caliphate”, this is ISIS 2.0. It is a fluid, menacing global guerilla insurrection, forging more extended affiliations and alliances when and where expedient, ISKP or IS Khorasan in Afghanistan becoming bed-fellows with the Taliban, IS tie-up`s with Boko Haram in Nigeria along with deeper penetration into Western Africa such as in Mali, Chad, Burkina Faso and the uranium rich strategically sensitive Niger, Lybia and the Sahel region (which is a hotbed of violent extremism since lawlessness engulfed Libya in 2011). IS 2.0 is also making inroads into the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt, strategically closer to Israel, and has recently reinforced links with Abu Sayyaf in the Philippines (especially in Marawi) where the 100 day battle ensued as 600 IS fighters were held by an iron fisted Duterte (with new Wilayats or Provinces declared by ISIS).

All the above are but a few examples of how IS are rebranding and regrouping when and where necessary. ISIS has now evolved from a Weberian state model (or a semi-government entity known as Tamkeen) to a lucid striking force as it`s maneuvering space has widened in an inter-connected porous global world “disorder”.

Conceptually re-adapting Immanuel Wallerstein`s 14 World Systems Theory, ISIS` core leadership may have been weakened but their periphery and semi-peripheral grass-roots world-wide franchises are emboldened.

Rumors are awash that Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, IS` delusional self-appointed Caliph still breathes. Irrespective of whether or not Baghdadi has a pulse, we live in an age of leaderless terror. 15 IS now develops an agile and broadened Weberian span of control 16 and a dehumanizing Kafkaesque bureaucratic 17 apparatus, enabling terror aspirants to climb up the food chain. IS Spokesman Al-Adnani`s demise certainly does not end IS. As Al-Qaeda`s example vividly attests, the killing of Bin Laden did not terminate an intellectually poisonous ideology. Fluid trans-national terrorist networks are Hydra-headed 18 serpents, where if one arch tyrant is killed, a hundred more ideologically infested zealots are ready to worm their way up the terror woodworks. The verge of defeat allows IS 2.0 to radically regroup and transform itself with a fluid globalist agenda – exporting hate further afield.

Territorial setbacks have dispersed and discouraged certain IS heathens. Such dispersion implies that authorities will be hunting in the shadows, making their lives infinitely harder. Many disgruntled and now rehabilitated fighters have returned to their original homeland where legal conundrums of possible prosecution beset them, but make no mistake, a lot of their remaining die-hard brain-washed sycophants aspire to re-unite, whether under the same banner or a re-incarnated off-shoot, both online and offline to bolster IS` `Second Coming` or ISIS 2.0.

Their insidious propaganda, operational savvy, financial know-how 19, monetary wherewithal (having now moved from taxation and oil money to daylight robbery, extortion 20 and black-mail) latent support, online recruitment, and media engagement cannot be underestimated.

IS operatives, decreed by a now dispersed head quarters, to remain relevant and lure recruits, are likely to keep unleashing unpredictable hell in Iraq and Syria itself. Especially vulnerable are the oil assets in Kirkuk and Northern Iraq (Kurdistan) and beyond, so too are attacks on high-profile limelight-stealing foreign diplomats and journalists in the region. The killing of James Foley, David Haines 21 and foreign journalists accentuates this.

ISIS 2.0 are swelling in numbers in far-flung parts of the world 22 and are likely to keep stirring up unrest, seeking sanctuary further afield, escalating tension, derailing short-term state-building and long-term nation 23 building efforts (“nations” are longer-term for they are the vessels into which “states” are poured) in Syria and Iraq. This will provide cover and limelight to the headline-hungry miscreants.

Some IS fighters, of which there are thousands, were opportunists who jumped onto the IS bandwagon when they gained territorial traction. These gold-diggers were handsomely paid – an average of USD $ 500 per month 24 (now reduced to a measly USD $ 50 a month). Such opportunists, many of whom were part of the former Iraqi Baathist Army, will now sell themselves to the highest bidder and join other economically rewarding extremist factions, materialistically morphing into blood-thirsty mercenaries.

More insidious, however, are the battle-hardened, committed to the cause, crazed fundamentalists with strategic tradecraft skills, who are hell-bent upon keeping IS alive and resurrecting a so-called Caliphate. Many such die-hard IS loyalists, will not travel far (not going to their countries of origin) for fear of being arrested and are likely to populate nearby conflict zones, especially those exploiting internecine sectarian Sunni and Shia grievances and other stateless war-torn lands.

Other brain-washed IS loyalists, such as so-called Jihadi brides 25 (a lot of whom are now embittered and traumatized widows) and Jihadi Junior Cubs (indoctrinated infants starting from tender four year olds upwards), will camouflage themselves as refugees, worming their way from Iraq and Syria to fragile states and power vacuums in Northern Africa, Southern and Central Asia, or via Manbij into Turkey – their essential gateway into the EU – where they will melt into civil society, tacitly reconnect with other returned members, and then wreak havoc.

On the brink of territorial desolation, IS will pursue global attacks to reinvigorate their brand. Snaking their sinister way into crippled and fractured states, seeking safe sanctuary in Libya 26, Tunisia 27, the Sinai, Somalia 28, the Philippines, to name but a few. They will seek shelter and safe-havens in such fragile and fragmented states. They will also exploit refugee camps and global migration patterns, from Jordan and Turkey to Calais and the Coast of Greece, in an increasingly insular, nationalistic, protectionist world saddled with the worst refugee, IDP and humanitarian crisis since World War II.

The bitter irony is that such an insular world will only breed more civilizational enmity between East and West, nourishing all extremes of an ever-swinging political pendulum.

ISIS 2.0 operatives are likely to birth and disband terror cells more swiftly, form sleeper cells (many sleeper cells in Germany were recently re-awakened which probably explains the recent IS attacks in Germany and perhaps even in Barcelona 29, Spain 30) and purposely remain dormant till the opportune attack time arrives.

ISIS 2.0 is likely to metastasize into a full-fledged, geographically dispersed guerilla insurgency using 5th generational assymetrical warfare tactics, which rely on deception, distraction, chaos, confusion and propoganda. History has proven, time and again, in cases such as the FARC in the cocaine kingdom of Colombia 31, Zapatistas in Mexico or ETA in Spain 32, that mobile agile insurgencies battling visible and fiercer foes bear the advantages of relative mobility and agility. Insurgencies, such as ISIS might be splintered and fragmented but can asymmetrically attack at a time and venue of their choice, exploiting the enemies` unpreparedness, where tactical shock and awe, and an air of ideological invincibility merge in the insurgents’ favor.

The international community is likely to be bedeviled by a return to a 1990`s style globally distributed terror landscape, often being bank-rolled from afar.

Proxy warfare, petro-politics, sectarian-saddled state-sponsored terrorism will all continue unabated, replenishing the coffers of gold-digging opportunity-exploiting defence contractors 33 and corporate warlords in an Eisenhowerian Military Industrial Congressional Complex (MICC) 34.

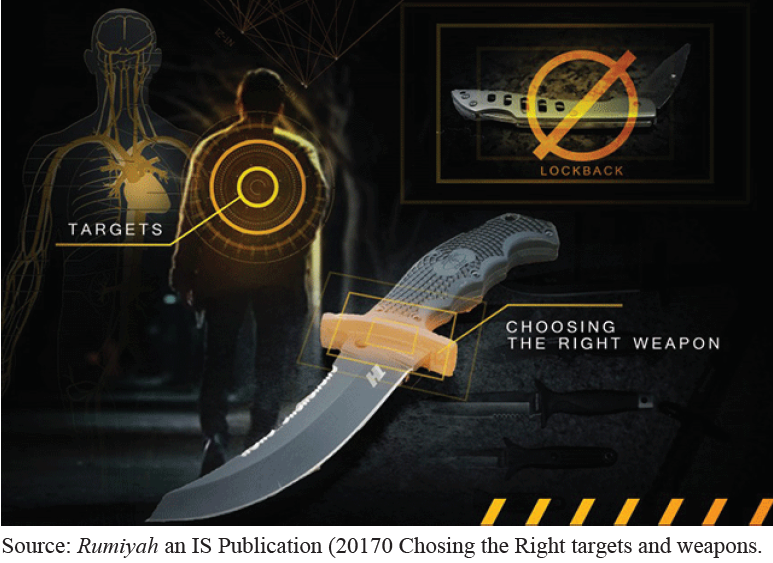

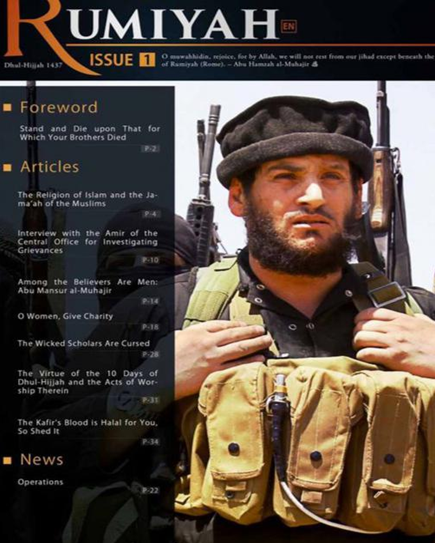

IS, by altering the nomemclature of its major foreign-language magazine from Dabiq to Rumiyah is brazenly shifting its follower’s focus from foretelling a glorious victory in Dabiq (which clearly failed to materialize) to fairy-tale predictions regarding the conquest of Rome. View below the types of articles they post in their English magazine. Rumiyah underscores the urgent need to take the battle to their prophesied crusader infidels in Western cities.

Source: Rumiyah (2017) IS Al Hayat Media Center, Issue 1.

Source: Rumiyah (2017) IS Al Hayat Media Center, Issue 1.

A Tale of the Tortoise and the Hare – Differences between IS vs. AQ – A Global House of Terror Divided? – Mujahideen 3.0

Whereas ISIS raced head-long like a hare towards a Caliphate, with rampant death and destruction, Al-Qaeda (AQ) 35 (by and large) took a tortoise-like calculated, step by step, gradualist incremental approach. IS believes in break-neck “revolution;” AQ prefer gradualist “evolution”. IS` top brass were only appeased by a Global Caliphate; AQ are more pragmatically satiated with a relatively quieter proto-Emirate – in Idlib for instance.

IS out rightly reject the Westphalian super-structure, for instance their Wilāyat al-Furāt breached the Sykes-Picot borders straddling Syria and Iraq, while AQ is deeply embedded in the political structures of Yemen and Syria, deceptively masking themselves as the “soft face” of appeasement. AQ have made overtures (much like the Taleban and Hamas) to politically negotiate and compromise with, and accommodate (in varying degrees) Western interlocutors within a democratic election-based Westphalian state paradigm.

Note how AQ keep rebranding themselves, this is a textbook asymmetric deception technique to confuse opponents and form previously unthinkable alliances. For instance, AQ`s al-Nusra became Jabhat Fateh al-Sham and are now convenient bed-fellows with the Western alliance against IS.

Where IS focused on total “disruption,” AQ emphasize on “creation” (cunning coalition-building, concensus mobilization with local party structures) embedding themselves within the political apparatus.

IS and AQ operate on a totally different time-horizon in terms of attack and action planning. AQ`s time-horizon stretches 5-10 years, whereas IS executed a knee -jerk immediate short-game. AQ`s devious longer- game 36 is a more sneaky, silent, sinister gradualist plan, now keen to exploit the IS territorial vacuum in the Middle East.

AQ, harvesting the poison that Zawahiri and Zarqawi have sewn, have taken a longer-term politically-strewn “strategic” approach (as seen in AQ`s Agenda 2020), whereas, IS will now unleash more low-intensity “tactical” level hit-and-run terror. AQ and its ever-multiplying regional off-shoots are deeply exploiting and embedded in the Syrian civil war and insurgency.

AQ is more selective and discerning vis-à-vis who it recruits amongst its ranks (for instance the 9/11 perpetrators were highly qualified in engineering and aviation), whereas, IS is much less selective with it`s intake, which is probably why IS are a much more “infiltrated” organization, inside-out and from top to bottom.

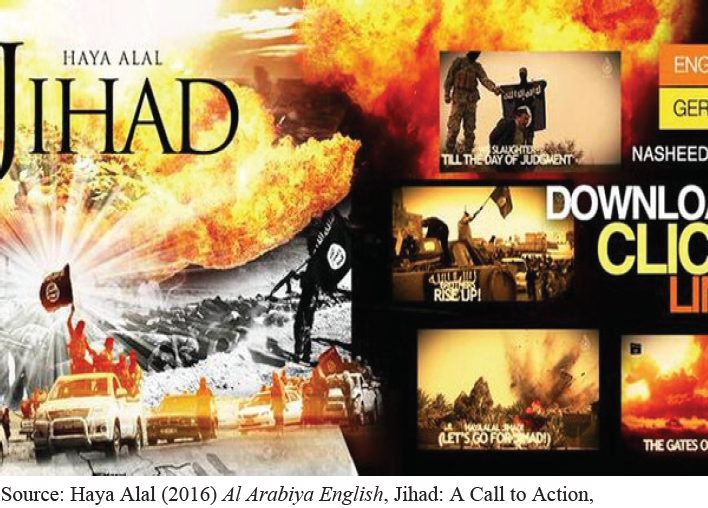

IS uses slick social media campaigns to lure adherents into their lion`s lair. They have a more engaged and robust online presence as opposed to the more traditional older-generation AQ. An example of a sick but slick IS campaign can be viewed here which urges an immediate call-to-action:

AQ would use older social media networking sites such as the now dinosaur-like MySpace 37 whereas IS swiftly moves into Next-Generation-Networks (NGN) and social media platforms.

AQ`s Zawahiri was never deemed a charismalic leader. He was, at best, an ineffective manager and the internal dissent between Zarqawi and Zawahiri caused many to defect from AQ and gave IS immediate manpower, territorial traction and land-grab from 2014 onwards. Whereas AQ is characterized as older militants, IS is manned and managed by younger zealots, so a generational gap is also at play. AQ recruits were geographically more locally concentrated whilst IS lured in an unprecedented number of foreign militants, and will now focus more on instigating far-flung home-grown 38 nihilism and terror, especially in the West, conflict-laden zones and regions bedeviled by fragile corruptible states.

IS losses work to AQ`s advantage. Both groups will keep trying to out-do each other in the global theater of militant extremism. Many former IS foot-soldiers, with no army to fight for, will be embraced (albeit suspiciously) with open arms by a re-invigorated AQ unleashing what I label a Mujahideen 3.0.

Whilst IS`s priority is now to wage a Crusade against Rumiyah, a term for ancient Rome of yore (exporting terror to Western capitals in other words), AQ`s focus is firmly (for now) rooted in the Middle East, Northern Africa where AQ Islamic Maghreb is active in Algeria and in South Asia, where AQIS and Taleban have a training complex in Kandahar, which the US took out in a Counter Terrorism (CT hereafter) raid 39.

The Syrian civil war break-down, an inability to agree on chemical Assad`s exit, the flammable tinderbox that is the “petro-state” of Kurdistan that will destabilize four neighboring states coupled with an internally disunited Iraq offers AQ ample marche de maneuver. AQ will endeavour to recapture territory. AQAP is already capitalizing upon anti-Houthi sentiments in Yemen, whose people, much like the persecuted Muslim Rohingyas, are seen as Children of a Lesser God in a cruel and harsh world.

Whereas IS and AQ are at ideological loggerheads, staunch dichotomies between IS and AQ should not prematurely be cast in stone, since both have already been forming (momentarily at least) joint alliances together in Yemen and Bangladesh of late, and certain attacks like the 2015 Charlie Hebdo in Paris reportedly involved both terror networks simultaneously. Shifting oaths of allegiance and marriages of convenience amongst militants are likely to be the norm in 2018, followed by the usual vicious cycle of splintering and mushrooming into more visceral factions.

As compared to IS 40, AQ now cunningly rebrands and name-changes into various reborn guises, reinvigorating a plethora of unsavoury new Jamaats and Ansaars who will keep competing for resources and enjoy more buy-in from militants in conflict zones.

As per this analyst, the split between IS ad AQ might also lead to what I term as a “Third Paradigm” of terror where smaller militias (as witnessed in Libya`s Sirte or Misrata) will find sectarian donors, including proxies and the usual state sponsors and engage in small-scale Emirate (rather than State) building. Such militias, unable to replicate IS`s Riyasat-Wilayat formula, will remain content with running their “mini-Emirates”. When North Africa offers multiple prison amnesties to Tunisian, Libyan, Egyptian and Algerian radicals, expect them to architect such “mini-Emirates” and militia factions to destabilize their more secular rulers.

With IS territorially cornered, AQ will certainly utilize the opportunity to springboard back up to the terror limelight, albeit in more subtler ways, working internally from “within the system”. However, AQ will not remain static but keep planning attacks abroad. On April 17, AQ claimed responsibility for the St. Petersburg metro bombing 41.

Although the schism between AQ and IS remains palpable, it is naïve to assume the two entities will not (at least temporarily) co-operate where and when it serves their vested interests 42. One pressing ideological menace ISIS poses is that, whereas, al-Qaeda believes that a Caliphate can only transpire after Uncle Sam and it`s European allies have been so scrupulously overwhelmed that they are impotent to impede upon Muslim majority lands 43, ISIS, by contrast, instigates a more urgent and pressing timeline for such a sinister agenda – with an undying conviction that the time for seizing, acquiring and conquering virtual cyber-territory (if no longer physical land) and brain-washing minds is now or never.

The Future of Terrorism – Cyber Caliphates and Digital Terror in 2018 and Beyond

As our world has evolved from “pens and papers” to “bits and bytes”, a bone-chilling Godless ISIS death cult and many future emerging terrorist cells have reconciled themselves to the reality of hosting a Cyber Caliphate spreading digital terror. They will use the information superhighway and social media to bypass mainstream media (which has already lost precious currency and credibility) and amplify their narrative. Online terror pushes our world from “Networks” to “Netwars”.

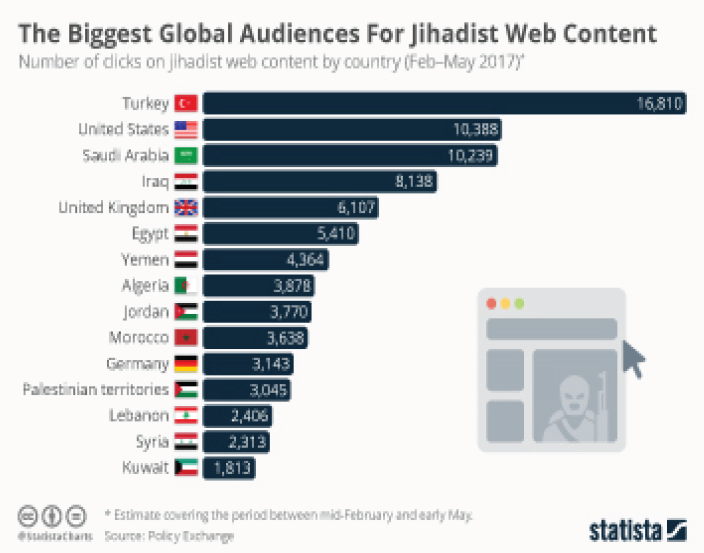

As the daunting infographic hereunder illustrates, empirical evidence suggests that there are massive audiences, the world over, susceptible to cyber-terrorist propaganda, below are the countries where they are most concentrated:

Source: Statista (Feb-May, 2017) The biggest global audiences for Jihadist Web Content.

Source: Statista (Feb-May, 2017) The biggest global audiences for Jihadist Web Content.

The above graph shockingly places the USA at number two with the UK and Germany trailing not far behind in terms of global audience demand for the consumption of extremist material. This might help explain the increasing number of attacks in these three countries in 2017.

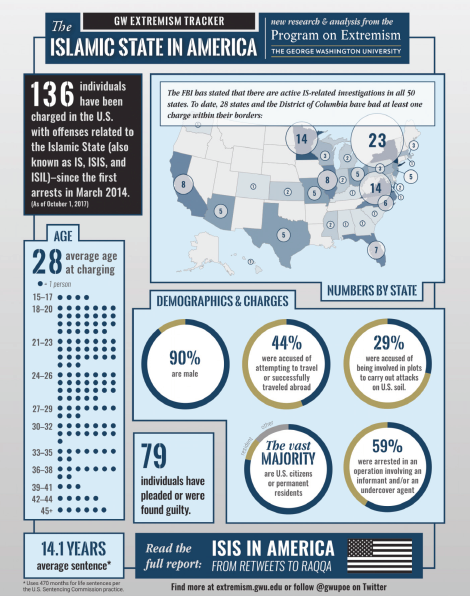

IS` growing presence in the USA is most alarming as the graph hereunder from September, 2017 depicts. Statistics from George Washington University (below) indicate that the FBI finds that 28 states and the District of Columbia are infested with IS related charges. 136 individuals have been charged since 2014 and the average age of perpetrators is 28. The huge demographic bulge in this particular age bracket is all the more worrisome. The numbers below merit cause for concern and might be suggestive that more Lower Manhattan type attacks maybe imminent.

Source: George Washington University September (2017) IS in America

Source: George Washington University September (2017) IS in America

IS are currently controlling a vast Digital Caliphate. IS social media propaganda spin masters cannot be stopped, in an age of ubiquitous social media. Where the deep dark 44 world wide web, non-traceable proxy servers 45, and cloud computing render information more susceptible to hacking from virtual private networks 46.

For every physical act of terror there is now a virtual counterpart, which compensates for territorial loss, and offers groups like IS an artificially exaggerated perception of strength, credibility and durability. This hyper-accelerates 47 the radicalization process and stimulates potent calls-to-action.

As the physical barriers to Hijra 48 close, the virtual doors to waging online so-called Jihad from afar open, where currently IS (and future mutations) emphasize the need to mount an increasing number of home-based localized terror operations, especially with knives and rental trucks (the Ohio state university attack started with a vehicle and ended with a knife).

IS has a sprawling digital media enterprise. 49 IS`s media assets range from e-zines (online magazines like Dabiq and Rumiyah) to online news agencies issuing digital press releases, such as Amaq, al-Hayat 50, al-Furqan 51 and Khilafah News and the weekly al-Nabah, to name but a few. IS have radio channels and frequencies in multiple languages dotted all around the globe.

Cyber terrorists 52 utilize online psychological warfare and emotional manipulation techniques to bolster recruitment, galvanize support and sway fence-sitters to their deadly cause. For example, IS used their social media platform Amaq to show videos of U.S. and Russian aerial strikes to emotionally seed doubts in the minds of reticent prospective recruits. Amaq then proliferates these videos onto “stand-alone” websites which are more concealed and take longer to censor, enabling their audience more access. The video for Muhammad Riyad, Germany`s Wurzberg attacker, is a similar case in point.

Under a Digital Caliphate 53 ISIS operatives and hackers in addition to VPN`s and proxies which offer instant anonymity 54, are also likely to use keystroke recognition devices and algorhythms to boost their search rankings. They may use anonymous browsers (such as TOR which masks online presence) cookies (which track the prey`s online activity), browser plug-ins (especially for Firefox which was conjured up by the hacking community), and other such “entrapment” information to uniquely identify a politically sensitive end-user.

IS uses existing apps such as Twitter`s Dawn app 55 and justpaste.it to keep operatives updated and use applications like Hallumy, often to translate content from Arabic to multiple languages.

IS leveraged digital platforms 56 to notify and warn audiences of their upcoming activities. For instance, images of IS` Turkey invasion appeared online just days before the ghastly Istanbul Reina attack.

They upload flashy infographics (to exaggerate their on-the-ground successes), videos, electronic-flyers often as a call to martyrdom operations.

As the image hereunder exhibits, IS use social media to expand far across all borders, passing violated images through Instagram to entice violent-prone lone offenders to mirror the same. They especially influence teenagers via Facebook and Whatsapp.

My forecast is that IS will now increasingly start using ephemeral social media such as Periscope and Snapchat, the latter widely used in the Arabian peninsula.

My forecast is that IS will now increasingly start using ephemeral social media such as Periscope and Snapchat, the latter widely used in the Arabian peninsula.

Such online activities are especially potent as terrorists manipulate electronic platforms to inculcate an “identity de-marginalization” in their potential recruits, through powerful peer pressure, crowd psychology and virtual group participation. Terrorists draw conflicted identities, especially those of lost souls, into spheres of evil by offering them a sense of inclusion and belonging not offered in their real physical world.

Social media can be extremely socially menacing. IS “de-individualize” humans, break them down into pieces, get fence-sitting prospective militants to copiously self-disclose facts about themselves (to be used later on for emotional blackmail or online abuse) coaxing them to carry out terror without their volition. This is using cyber influencing to play on our most viscerally primal impulses and drivers as humans 57.

IS digitally migrated from in-house “proprietary” software to “off-the-shelf” easily accessible faster-paced software. Whereas AQ would write their own sophisticated code 58, IS utilizes easily accessible off-the-shelf software, and migrates from from classic websites to encrypted social media networks 59 such as Telegram (a micro-blogging channel and instant messaging service), as well as Surespot 60, Kik, Wicker and Twitter 61. Users who post and proliferate their content are often contacted to resurrect the now Digital Caliphate.

Twitter 62 and Telegram are by far IS`s preferred social media platforms because it is easier to open accounts on these channels and they tend to be more politicized than other platforms. IS, would, on average, amass at least 14,000 online followers daily, via various anonymous accounts. Even though Twitter 63 (and other social media platforms) have belt-tightened, shutting down 250,000 online accounts, yet a lot still needs to be done. AQ`s As-Sahab account only had 20,000 Twitter 64 followers by contrast.

IS uses its online media empire to train combatants on how to use weapons, where and when to strike, ideal targets to aim at. These are practically virtual online training and indoctrination sessions:

In such a hauntingly Huxley-like Brave New World Order, lonely online misfits are seduced by the dystopian “parallel universe” ISIS sucks them into. Such growing “lone offenders” are likely to operate and seek inspiration from multiple online platforms, deploying low to medium scale intensity attacks within the Internet of “Stings”.

Slightly more sophisticated cyber terrorists will graduate to: installing malware 65, ransomware 66 (holding end user`s sites hostage till handsome ransom money is paid), firewall leaks, online identity theft (phishing), blended threats (a cocktail of viruses) 67, privacy breaches 68, a Denial of Service (DDos) attack by overwhelming servers and distributing electronic kill lists.

IS often use cyber media to post gruesome execution pictures. A recent example of this was when ISIS supporters promised to bring mayhem to the 2018 Russian Soccer World Cup and have uploaded a series of stomach-turning posters depicting a sick execution of the prodigious Neymar and Lionel Messi. Through web defacement IS leaves unsavoury images 69, lists and messages to trigger “lone-offenders” into deadly action.

Consistently pushing out their vile propaganda on popular channels broadens their consumer base, reach and distribution networks 70. Such a stream of constant engagement renders credibility and augments their virtual support base to a generation unhealthily glued to their smart-phone screens and addictively glued to social media.

To elevate their online visibility and drive interest IS deploys hash tagging 71 (easily searchable words, especially on Twitter 72, by Tweeting certain keywords preceded by a hash tag), like ISIS Daesh Caliphate Khilafah al-Furqan and al-Hyat 73 or common hashtags 74 such as #KhilafaEn #alfurqan #alhayat which in turn eerily climb to the top of multi-platforms and Google search 75 rankings 76. As these hash tags trend right on top, they are consumed by impressionable minds who go on to further research these concepts, which in marketing is known as a “pull” technique to increase conversion ratio. These hash tags are often linked to posts related to a bellicose call-to-action (for instance to increasingly use knives and vehicles to attack innocent civilians) or belligerent crusades, and those who retweet 77 such messages fall under IS social media army`s potential recruitment radar, as being sympathetic to their cause.

Worryingly the circle of IS online sympathizers might be much larger than analysts envisage – claimed to currently be 23,000 in the UK alone. When terror sympathizers and social misfits on the fringes of society, recycle, retweet or upload content onto their social media time-lines and walls the “Like” button by their virtual friends gives them instant gratification, status and validation 78 in our dystopian post-industrial information age, where “ghettoized online communities” are increasingly living their lives more on social media and less in the physical realm.

Such cliquish “ghettoized online communities”, especially amongst hate and terror groups, often form “echo chambers” where the group reinforces received messages – focusing on perpetuating a victimhood narrative, prevailing global injustice, the failure of globalization, a binary “us versus them or us versus the world” mentality, foreign policy grievances – necessary for legitimizing terror. Such self-reinforcing “echo chambers” trigger self-validation which is the fuel needed to animate radicals to attack, often soft civilian targets.

Such “echo chambers” are often (inadvertently) designed by social media platforms themselves, where your online behavior and preferences are tracked and your timeline gets full of messages or hashtags you and your circle of influence have posted. Such predictive behavior analytics, Artifical Intelligence and manipulated content reinforce existing world-views and narratives, no matter how deviant or despicable.

IS often organizes, for its online adherents 79, patterns of activity with which to pledge their allegiance as a sign of initiation or a rite of passage. This precipitates `lone wolf` 80 attacks. IS also deploys armies of cowardly keyboard warriors to keep cyber bullying 81, threatening, trolling and irritating reporters and counter terrorist analysts who vehemently oppose them and officials who institute harsher policies against them. Cyber terrorists of the future will even be able to “tease out” future trends and policy insights from social media character profiles 82.

For cyber terrorists, there is likely to be a precipitous rise in cyber crime 83 to fund their low-scale attacks. Such scams currently include online bank account infiltration for quick funds transfer, e-black-mailing and threats.

IS 2.0 and their forthcoming offshoots, with an enhanced media product, high-resolution graphics and technical quality, professional production capabilities would/will often broadcast their terror in real-time, glorifying gory violence to seduce the adventure prone (often video-game obsessed) adrenaline-fuelled youth male demographic, in an almost surreal manner.

Such bloodthirsty (video-game like violent) were uploaded to sites like YouTube 84 for optimal viewership and linked to keywords even in the video gaming community, to widen their recruitment net with a many-to-many as well as peer-to-peer (P2P) recruitment modality paradigm. IS would fine tune, narrow-cast and market segment their messages based on age, gender, demography and disposable income. From the younger to older online communities.

One lurid emotional example of this is by having handsome soldiers romantically seduce aspiring so-called Jihadi Janes 85 on Skype and WhatsApp, showering them with attention, praise and lavish gifts (physically delivered to them from afar), promising them a Halal relationship of intimacy through marriage if they came and joined them in Iraq or Syria`s Caliphate 86.

Cyber-brainwashing of impressionable minds on the social periphery is now IS` perceived historical calling; an inevitability in the battle of ideas; a digital reality on the insidious information superhighway.

Future Emerging Cyber Threats

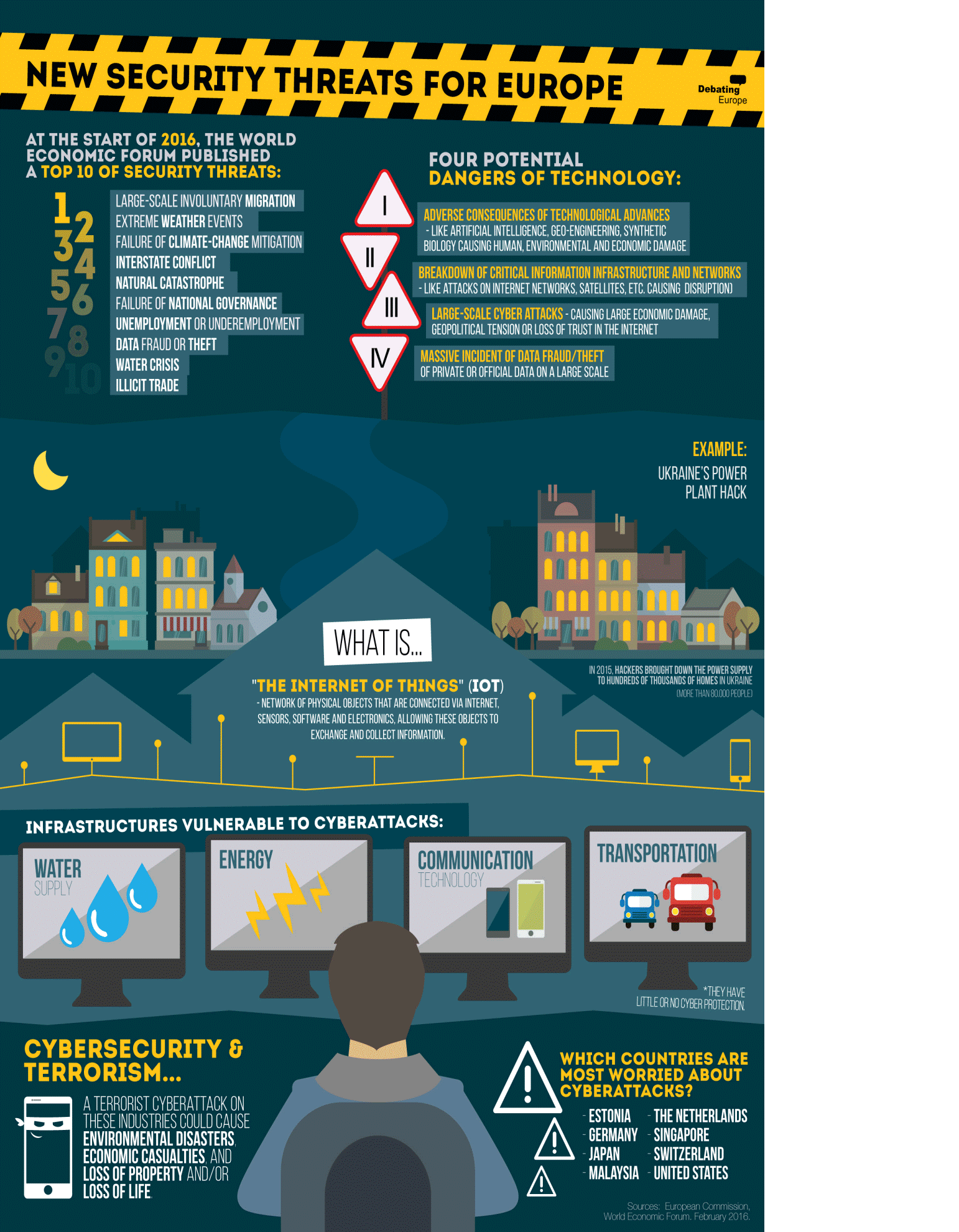

Future terrorists are prone to engage in Cyberspace Cyberwarfare where the virtual battle space targets entire Industrial Control Systems (ICS), electricity grids 87 (already hacked by spies back in 2009), mass transit and transportation systems, and entire utility networks (water, gas, power) on which our modern lives depend upon. As the image below cautions:

Source: European Commission (2016) New Cyber security threats for Europe

Source: European Commission (2016) New Cyber security threats for Europe

Future cyber terrorists will have their eyes set on end-to-end encryption networks. Entire Smart Cities (including Islamabad 88) and Smart Systems could be compromised. For safety purposes, many former (now rehabilitated) terror Czars advise that industrially sensitive systems should be disconnected from the internet altogether – be they transport hubs, energy and electricity infrastructure, thermal or nuclear installations.

Wi-Fi, SCADA and ICS systems 89 are all inter-connected which can be piggy-backed and infiltrated in our day and age. Any mass transit system such as trains (the terrible train accident in Bad Abling Germany 2016 caused due to a single moment of distraction from a computer game), buses, and driverless cars 90 are all prone to hacking which can cause huge fatalities. We now live in a world where a USD $ 50 off-the-shelf Radio Frequency device can hack an entire car, control its engine and imperil all seated passengers.

The aviation industry is particularly sensitive to cyber susceptibilities, where Wifi networks and cellular links have already been ethically hacked by white hackers. This exhibits huge potential system weaknesses 91. Ethical hackers have already infiltrated second tier systems, such as communication systems, take off and landing strip application and control systems.

In 2012, Newark International Airport came to a grinding standstill by a USD $ 50 GPS signal jammer which disrupted the entire airport and even Port Authority`s communication systems. On June 21, 2015 OT airline had a cyber breach. On July 8, 2015 United Airlines had to cancel 4900 flights, due to a single cyber glitch and in 2015 United Airlines gave a US $ 1 million bounty to ethical hackers who successfully infiltrated their systems. Delta Airlines 92 had one single power outage which triggered a computer glitch grounding thousands of flights, disrupting its systems worldwide.

Cyber terrorists hacking into peripheral second tier systems or grids can cause such power outages, wreaking havoc on carrier`s reservations systems. The Delta Airlines meltdown testifies to ageing equipment and (back then) a potential lack of alertness. On July 20th South West Airlines had to cancel 2300 flights due to a router problem, whereby the airline suffered the worst system outage in it’s history along with a failure of all backup systems 93. This not only accentuates the need for cyber contingency planning and safer redundant N + 1 network configurations 94 but also exposes the dark reality that a tech savvy hacker who can disrupt networking systems and routers can make life a living hell for commercial aviation and any other industry they so chose.

British Airways has encountered massive IT failures. American Airlines faced cyber glitches due to which Miami and Denver airports had to temporarily close down.

Chronicling such vulnerabilities seek not to stoke hysteric alarmism but rather to underscore the urgency that there are multiple digital vulnerability points which terrorists can prey upon. The Holy Grail of Cyber Security is beyond our comprehension. We are only coming to terms with it. This is not pie in the sky, nor drawing daggers in the dark but concrete real-life empirical industry-based examples which can all too easily be exploited by tech savvy terrorist or criminal mavericks.

The International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) kick-started a program titled `No Country Left Behind` (NCLB) 95 which is a positive start provided member states follow-up. Of particular relevance are ICAO`s SARP`s 96/documents 17, 187 and 394 which address cyber vulnerabilities. The US Federal Aviation Authority is rapidly seeking to comply with ICAO`s NCLB initiative. Other transport and infrastructure industries need to intensify and hasten the pace of their cyber risk preparedness and disaster recovery based contingency planning.

Advanced simulation and preparedness exercises are rapidly required to future-proof and secure-proof a brave new world based on advanced automation and analytics. One interesting example is The U.S. Department of Justice which started researching into possible cyber threats to driverless cars, as external devices can easily hack the engine and purposely cause atrocious road accidents.

Current and future cyber-warfare entail both offensive and defensive tactics, espionage and high-scale sabotage. Nations must develop virtual warfare readiness capabilities. The advent of anti-western anti-civilization terror groups imply that such eye-watering cyber terror attacks are likely to intensify sooner rather than later.

Future cyber shockwaves as described above might serve to very painfully illustrate how woefully unprepared governments are for such digital assaults, even though most governments are already tacitly engaged in Cyber Warfare themselves 97.

Cyber terrorism, by leveraging encryption apps along with potential alliances on the deep dark web with criminal syndicates may see new spheres of virtual evil emerge. The deep dark web is much tougher to monitor so legal cyber armies will be chasing terrorists and criminal syndicates in the “digital shadows”, in the opaque deeper recesses of the world wide web, where terrorists are likely to remain several steps ahead, rendering their task infinitely more arduous.

ISIS 2.0 and other cyber MNT`s (Multi-National Terrorists) are likely to intensify a so-called Electronic Jihad of incitement. To fund such campaigns collaborative cyber fund-raising modalities will develop (terrorists already use mobile payments, digital wallets leveraging high tele-density in developing countries, to crypto-currencies like Bitcoin 98 and crowd-sourcing/crowd-funding terror campaigns). These finances will be used for terror recruitment, to spread Dawa (a skewered and distorted interpretation of the religion). Even though Bitcoin issued new money laundering guidelines 99 the risk of funding cyber warfare via crypto currencies remains real and imminent.

On an institutional level, a delicate, finely-tuned sensible balance has to be sought. One concrete recommendation which this author recommends that the U.S. Federal Communications Comission (FCC), Pakistan`s PTA, PEMRA and other similar global media and telecom watchdogs ensure and decree is that only verified social media accounts be allowed to open or access their social media accounts via VPN`s 100 or specialized browsers 101, or at the very least, levy a monthly fee for so doing, whereby online payments would act both as a deterrence plus leave a digital trail of footprints enabling Counter Terrorism (CT) authorities to swiftly locate and triangulate the user`s physical location.

On a social level, online users of the world must unite 102 to form electronic counter extremist advocacy campaign groups. A lot is at stake. By not doing so we have a lot to lose. By uniting we have everything to gain. The civilized world must counter terrorism`s next generation electronic psychological warfare 103. Recent online activism sprung from noteworthy campaigns such as #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter illustrate that positive messaging on social networking 104 sites yield positive awareness, outreach, sensitization, attitudinal and behavioral change, essential ammunition to delegitimize the nefarious propaganda of militancy and hate.

Both offline but now especially online, the international community needs to roll out more podcasts, video logs, live streams, outreach programs and debates centered around cyber counter narrative programs, peer-to-peer and many-to-many counter messaging counter-extremism initiatives and deployment of counter terror hashtag activism ( #CVE or Countering Violent Extremism is one stellar example). Global engagement initiatives are afoot but need to be less fragmented and more concerted.

With fear and loathing spreading like wildfire on our online world, and the weaponization of social networks, social media behemoths need to more actively engage in content moderation and control. Suspending 250,000 ISIS linked Twitter accounts is a start, a stepping stone, but a lot more is required to take substantive moves forward 105.

Terrorists have weaponized social networks, therefore social media and telecom operators would be well advised to rapidly suspend a “cluster” of accounts which publish inflammatory hashtags such as the ones cited earlier in this paper. This can be achieved via Behavioral Mapping and Advanced Analytics. Suspicious Activity Reporting (SAR`s) which have made steady milestones in the financial sector need to broaden their reach into other industries especially in the technology, social media, telecom (TMT) and other sensitive sectors (defence, nuclear, critical infrastructure).

Thwarting cyber-terrorism requires a concerted multi-stakeholder effort and engagement 106. The international community must prevent terrorism but preserve innovation. This is a judicious balancing act at the easiest of times. An urgent response with special Anti-Cyber Terror task force and monitoring units (like Pakistan`s FIA Cyber Security division), harsher Security Hash Algorhythm (SHA) encryption procotols, deeper probing and penetration testing constitute steps in the right direction.

Admittedly, CEO`s of publically listed and traded tech companies of course worry about their PR and reputation, especially seeking never going to trial, neither with terrorism`s family victims and affectees nor with liberal free speech activists, as it dents their equity value and stock price. Such social media and online companies and their Senior Management remain stuck between a rock and a hard place. If they are seen as too lenient they are labeled as terror sympathizers, if they crack-down hard they are seen as Orwellian Big Brothers watching over an over-surveyed citizenry whose 1st amendment and freedom of speech rights are being curtailed.

Sources reveal that “passive engagement” is already being conducted between the private sector and global law enforcement agencies behind the scenes. Such public-private partnerships must intensify, even if they remain, by means of necessity, below the radar. Reconciling national security and a surveillance state with online privacy 107 and civil liberties 108 will always remain a hyper sensitive and hotly contested issue, as the promulgation of Pakistan`s Cyber Crime Bill attests.

States need more trained Certified Electronic Ethical Hackers (CEH) 109. Better network defence and cyber security capabilities and architectures are needed which deny current and future terrorists “cyber sanctuaries” who can wreak catastrophic scale atrocities. A maximization of cyber combat readiness and resilience is long overdue, including in the private sector.

As the future unfurls, in an age where Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, Advanced Analytics, Quantum and Cloud computing redefine how marketplaces operate, more industries will be dependent upon and vulnerable to mission-critical digital infrastructure running entire industries. Countering cyber terrorism 110 must be a top-priority and strategy for all serious stakeholders and innovators in an increasingly compromised hyper-connected, cyber risk-prone virtual world of terror.

Legality Governing Cyber Terrorism: New Battlefields Old Laws?

In an increasingly compromised cyber risk-prone virtual world, let us now impartially review measures which the international community has initiated to legally counter this palpable menace. The international community has stepped up its efforts to regulate and police (to the best of their abilities) the world wide web and cyber space, a de facto ungovernable space (due to its increasingly open source cross-border nature). Under the auspices of Article 51 of the UN Charter, countries have the right to self-defence, this definition now encouragingly broadened its remit to encompass protection from cyber attacks also.

The Budapest Convention on Cyber-Crime 111, the Talinn Manual on cyber self-defence and cyber warfare 112, NATO`s Cyber Defence Pledge of July 2016, Article 3 of the Washington Treaty are just some major multi-lateral legal milestones governing cyber-space, cyber warfare and cyber security.

UNDOC and UNICTRAL deal with cyber issues and the United Nations Group of Government Experts (UN GGE), comprising of twenty five nations, advanced a series of recommendations for countries to protect themselves from cyber threats. The International Multilateral Partnership Against Cyber Threats (IMPACT) is the first United Nations-lead cybersecurity alliance. It is the first comprehensive Public-Private Partnership (PPP) against cyber threats. It remains a politically neutral global platform bringing together world governments, academia and industry to boost our global community’s cyber threat capabilities. IMPACT’s Global Response Centre acts as the first line of defence against cyber threats.

The OECD`s 35 member states achieved commendable work on digital security risk 113 management 114, especially on issues pertaining to critical infrastructure (grids, power stations, transport hubs). In 2016, the OSCE`s 57 member states issued confidence building measures related to cyber resilience, especially with regards to interception and escalation mitigation.

International forums currently tackling cyber security include the Billington Cybersecurity Summit, the Internet Governance Forum which has undertaken laudable efforts towards incident response management and cyber security teams and the Global Counter-Terrorism Forum (GCTF). 115

Despite all the above, however, Silicone Valley, ICT tech companies and social media behemoths need to be more integrated and involved. Admirably, Microsoft proposed international legal norms that could govern cyber-security which was quite a break-through from the private sector but their norms need to be followed up. The above measures, (with further refinements and necessary amendments) can act as a future industry blueprint.

Critical facilities (especially in sensitive industries such as nuclear and thermal) pose a larger threat and are currently not fully cyber protected. A comprehensive cross-border Threat Vulnerability Assesment needs to take place 116 and prosecution norms need to be better defined. Laggard companies failing to comply with these emerging precautionary measures should at first be fined and subsequently perhaps black listed for non-compliance. Global supply chains are vertically and horizontally interdependent and inter-related, where digital system dependencies are higher than ever before, whereby a single glitch in one virtual application, or a cyber security breach of any kind, is likely to have monumentally negative ramifications for entire industries. This paper shed light to some concerning examples from the aviation industry. This alone should jolt industries and governments into action.

A major problem with most of the aforementioned legal instruments is that they are, voluntary non-binding limiting norms rather than mandatory legally binding decrees. The Conventions, guidelines and legislation highlighted above are broad recommendations and general principles as opposed to legally enforceable instruments of potency. More substantive and specific measures are needed as our world vulnerably teeter`s on a knife edge of cyber uncertainty, where criminals, terrorists and miscreants may/are forging Unholy Alliances to undermine the cyber world order.

Nation-states can no longer afford to be negligent and have to rapidly undertake compliance of the above as legally enforceable and immediately binding, or potentially be consigned to the scrapbook of history.

Selected Bibliography

Khalid, Ozer September 13 (2017) Volume 12, Number 3, Criterion Quarterly, Challenges and Opportunities in a Post-ISIS Territorial World – An Ongoing Global Menace. The article is accessible to readers at https://criterion-quarterly.com/challenges-opportunities-post-isis-territorial-world/

Khalid, Ozer (2016) Nightmare in Nice, The News International, Jang Group, July 18, 2016 and the article can be accessed at https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/135665-Nightmare-in-Nice

Khalid, Ozer (2017) Blood and bravery in London, March 27, 2017, The Express Tribune, part of the International Herald Tribune, March 27, 2017. At https://tribune.com.pk/story/1366325/blood-bravery-london/

Foucault in Foucault, Michel (1972) The Archeology of Knowledge & The Discourse on Language. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.

Foucault, Michel (1977) “What Is an Author” Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews. Ed. Donald F. Bouchard. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977. pp. 114-37.

Foucault, M. (1975) Surveiller et Punir: Naisance de la Prison, Éditions Gullimard.

Nouriani, D. Steven (Winter 2011) “The Defensive Misappropriation and Corruption of Cultural Symbols”. Jung Journal: Culture and Psyche. 5 (1): pp. 19–30.

Mückenberger, Christiane (1993), “Nosferatu”, in Dahlke, Günther; Karl, Günter, Deutsche Spielfilme von den Anfängen bis 1933 (in German), Berlin: Henschel Verlag, pp. 69-72.

Nye, Joseph (2004) in “Soft Power and American Foreign Policy.” Political Science Quarterly 119.2 (2004): pp. 255-70.

Gayle, Damien (2017) “Last Isis fighters in Raqqa broker deal to leave Syrian city – local official”. The Guardian, 14 October, 2017.

Hawar News Agency. 16 October (2017).

“US expands air base in northern Syria for use in battle for Raqqa” (2017) Stars and Stripes. 3 April 2017.

Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi (2016) “Dissent in the Islamic State’s Yemen Affiliates: Documents, Translation & Analysis,” Combatting Terrorism Center (CTC)

Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi (2016) “Dissent in the Islamic State: Abu Al-Faruq Al-Masri’s Meesgae on the Manhaj: Documents, Translation & Analysis,” Combating Terrorism Center (CTC) 2016.

Wallerstein, I. (2000) The Essential Wallerstein. New York, NY: The New Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel (1930) “The AZ Guide to Modern Social and Political Theorists. Ed. Noel Parker and Stuart Sim. Hertfordshire: Prentice Hall/Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1997. pp. 77-373.

Marc Sageman (2008) Leaderless Jihad: Terror Networks in the Twenty-First Century, (Philadelphia, PA: University Of Pennsylvania Press).

Fayol, Henri (1949). General and Industrial Management. New York: Pitman Publishing. pp. 105–112

Weber, Max (1904) Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus translated in English as The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

Richard Swedberg; Ola Agevall (2005) The Max Weber dictionary: key words and central concepts. Stanford University Press. pp. 17–22.

Kafka, Franz (1968). The Castle. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Kafka, Franz (1998). The Trial. New York: Schocken Books.

Kafka, Franz (1996) The Metamorphosis and Other Stories. New York: Barnes & Noble.

Cooper, Helene (2011) “Obama Announces Killing of Osama bin Laden”. The New York Times. May 1, 2011.

Philip Sherwell (2011) «Osama bin Laden killed: Behind the scenes of the deadly raid». The Daily Telegraph. London.

Dilanian, Ken (2011) “CIA led U.S. special forces mission against Osama bin Laden”. Los Angeles Times. May 7, 2011.

C. Christine Fair (2011) “The bin Laden aftermath: The U.S. shouldn’t hold Pakistan’s military against Pakistan’s civilians”. Foreign Policy. May 4, 2011.

Graves, Robert (1960) The Greek Myths, Penguin Books, pp. 70-470

“Hydra.” Myths and Legends of the World (2001) Encyclopedia.

Moore, Jack (2014) “Mosul Seized: Jihadis Loot $429m from City’s Central Bank to Make Isis World’s Richest Terror Force”. International Business Times. UK, 11 June, 2014.

Kulish, Matthew Rosenberg, Nicholas; Myers, Steven Lee (2015) “Predatory Islamic State Wrings Money From Those It Rules”. The New York Times.

Revkin, Mara, “The Legal Foundations of the Islamic State,” The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World, July 2016, 16;

Gordon, Matthew S. The Rise of Islam. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2005

Peritz, Aki (2015) “How Iraq Subsidizes Islamic State”. The New York Times, 4 February, 2015.

Bothelo, Greg (2014) “ISIS Executes British Aid Worker David Haines; Cameron Vows Justice.” CNN.

Michaels, Jim (2016). “New U.S. intelligence estimate sees 20-25K ISIL fighters”. USA Today. Washington, DC. 4 February, 2016.

Nicks, Denver (2016) ISIS Fighters just got a huge paycut, Time Magazine, January 19, 2016.

Ough, Tom; Smith, Hannah Lucinda (2015) “From Loving Rihanna to Loving Jihad – Mohammad Uddin tells how daughter Sharmeena Begum became the first British schoolgirl to join ISIS in Syria”. The Times. 14, March, 2015

Bennhold, Katrin (2015) “‘They were the girls you wanted to be like’: How teenage rebellion sends girls into the arms of ISIL”. National Post, 18 August, 2015.

Sciutto, Jim; Starr, Barbara; Liptak, Kevin (2016) “ISIS fighters in Libya surge as group suffers setbacks in Syria, Iraq”. Washington, DC: broadcast on CNN on the 4th of February, 2016.

Carlino, Ludovico (2016) «Islamic State attack on Ben Guerdane indicates shift in group›s Tunisia strategy, to trigger insurgency». Jane›s Defence Weekly. 9 March, 2016

Desk, News (2016) “ISIS terrorists ambush 4 Tunisian soldiers in Kasserine”, 30 March, 2016.

Tin, Alex (2016) “ISIS faction raises black flag over Somali port town”. Telecast on cbsnews.com. CBS News.

Hatton, Barry; Wilson, Joseph (2017) “Barcelona attack: Van driver kills 13, injures 100”, 17 August, 2017.

Alexander, Harriet (2017) “Massive explosion at Alcanar house on Wednesday night linked to Barcelona terror attack”. telegraph.co.uk. The Telegraph. August 2017.

Molano, Alfredo ( 2004) James Graham (Translator), ed. Loyal Soldiers in the Cocaine Kingdom: Tales of Drugs, Mules, and Gunmen. Columbia University Press.

Perkins, John (2005). Confessions of an Economic Hit Man. Ebury Press.

Friedrich Hayek (1944) The Road to Serfdom.

Wright Mills C (1963) Power, Politics and People, (New York) 1963, pp.1-173.

Geltzer, A. (2008) Six rather unexplored assumptions about Al Qaeda. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 1, pp. 393–403.

Lister R. Charles (2016) The Syrian Jihad, Al Qaeda, the Islamic State and the evolution of an insurgency. Oxford University Press.

Kohlmann, E. F. (2008) Al Qaida’s MySpace: terrorists recruitment on the internet.

CTC Sentinel, 1, 2.

Kohlmann, E. (2006) The real online terrorist threat. Foreign Affairs, 85(5), pp. 115– 124.

Yager, Jordy (2010) “Jordy Yager, “Former intel chief: Homegrown terrorism is a ‘devil of a problem,’” ‘’The Hill’’, 25, July, 2010.

Stern, Berger (2015) ISIS: The state of terror. London: William Collins.

“Alleged AQ-Linked Group Claims St. Petersburg Metro Bombing” (2017) SITE Intelligence Group. April, 2017.

Fahmy, Omar (2015) “Al Qaeda calls Islamic State illegitimate but suggests cooperation”. Reuters, 9 September 2015.

Everton, Sean F. (2012) Disrupting Dark Networks. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Eckersley, Peter (2014) “How Unique Is Your Web Browser?” (PDF). Electronics Frontier Foundation. Springer. 15 October, 2014.

Kleinberg, Jon. (1999) “Authoritative Sources in a Hyperlinked Environment.” Journal of the ACM 46 (5): pp. 604-32.

Jeff Lewis (2015) Media, Culture and Human Violence, Rowman and Littlefield, Lanham, MD.

Al Hayat Media Centre (2014) There’s no life without Jihad. YouTube, June 19, 2014.

Dabiq (2014) “The Return of the Khilafah”, Issue 1.

Cisco Systems, Inc. (2004). Internetworking Technologies Handbook. Networking Technology Series (4 ed.). Cisco Press. pp. 130-235.

Jankiewicz, J. Loughney, T. Narten (2011) “IPv6 Node Requirements”.

Lewis, Mark (2006) Comparing, designing, and deploying VPNs (1st print. ed.). Indianapolis, Ind.: Cisco Press. pp. 4–17.

Conway, M. (2003) What is cyberterrorism? The story so far. Journal of Information Warfare, 2(2), pp. 33–42.

Denning, D. (2010) Terror’s web: how the internet is transforming terrorism. In M. Yar, & Y. Jewekes (Eds.), Handbook of Internet Crime (pp. 194–212). Willan Publishers.

Christopherson, K. (2007) The positive and negative implications of anonymity in internet social interactions: Bon the internet, nobody knows You’re a dog^. Computers in Human Behavior, 23, pp. 3038–3056.

Chasmar, J. (2014) ISIL using twitter app ‘Dawn’ to keep Jihadists updated, in the Washington Times.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1969) The human choice: Individuation, reason, and order vs. deindividuation, impulse, and chaos. In W. J. Arnold & D. Levine (Eds.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (vol. 17, pp. 237–307). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Jenkins, Brian (2012) “Is Al Qaeda’s Internet Strategy Working?”.

Contena, B., Loscalzo, Y., & Taddei, S (2015) Surfing on social network sites: a comprehensive instrument to evaluate online self-disclosure and related issues. Computers in Human Behaviour, 49, pp. 30–37.

Maschke, George (2015) “Developer’s Silence Raises Concern About Surespot Encrypted Messenger”. AntiPolygraph.org, 7 June, 2015.

Berger, Perez (2016) “Occasional Paper The Islamic State’s Diminishing Returns on Twitter How suspensions are limiting the social networks of English-speaking ISIS supporters.” GW Program on Extremism

El Akkad, Omar (2012) “Why Twitter’s censorship plan is better than you think”. The Globe and Mail.

Berger, Morgan (2015) “Defining and describing the population of ISIS supporters on Twitter”. The Brookings Institution.

Oremus, Will (2011) “Twitter of Terror”. Slate Magazine. December 23, 2011.

Bacon, John (2015) “Islamic State Threatens ‘War’ on Twitter Co-founder.” USA Today.

Barrett, Devlin (2015) “U.S. Suspects Hackers in China Breached About four (4) Million People’s Records, Officials Say”. Wall Street Journal. 5 June, 2015.

Claude H. Miller; Jonathan Matusitz; Dan O’Hair; Jacqueline Eckstein (2008) Terrorism: Communication and Rhetorical Perspectives. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

YouTube Statistics (2014) Viewership. Available at https://www.youtube.com/yt/ press/en-GB/statistics.html

ITV News (2014) 15 K items of jihadist propaganda removed from the internet.

Mosquewatch.blogspot.com (2007) Paltalk hosts Al-Qaeda, Hizballah, and Hamas chat rooms.

Umm Layth (2015). Personal Tumblr Blog of a women who travelled to understand ISIS.

GlobalWebIndex. n.d. (2014) “Altersverteilung der aktiven Nutzer von Tumblr weltweit im 4. Quartal 2014”. Statista.

Caffrey, C. (2015) Blogging in the 2000s. Salem Press Encyclopedia.

Turton, William (2016) «Cryptography expert casts doubt on encryption in ISIS› favorite messaging app». The Daily Dot. 19 November, 2016.

Clary, Grayson (2017) “The Flaw in ISIS’s Favorite Messaging App”. The Atlantic.

Selfhout, M., Burk, S., Branje, J., Denissen, M., & Meeus, W. (2010) Emerging late adolescent friendship networks and big five personality traits: a social network approach. Journal of personality, 78(2), pp. 509–538.

Farwell, J. (2014) “The Media Strategy of ISIS”. Survival: Global Politics and Strategies.

Katz, R. (2014) Follow ISIS on twitter: a special report on the use of social media by Jihadists. SITE intelligence group.

Channel 4 News (2014) IS supporters demand police #FreeShamiWitness after arrest.

Austin, David (2011) “How Google Finds Your Needle in the Web’s Haystack.” Feature Column.

We Are Social. n.d. (2015). “Ranking der größten Social Networks und Messenger nach der Anzahl der monatlich aktiven Nutzer (MAU) im Jahr 2015 (in Millionen)”. Statista.

Klausen, J. (2015) “Tweeting the Jihad: Social Media Networks of Western Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq”. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism.

Fiegerman, S. (2014) Facebook Messenger now has 500 million monthly active users.

Irshaid, F. (2014) How Isis is spreading its message online. BBC News.

Spaaij, Ramón (2010) “The enigma of lone wolf terrorism: An assessment.”. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 33 (9): 853–869.

Goodboy, A., & Martin, M. (2015) The personality of a cyber-bully: examining the dark triad. Computers in Human Behaviour, 49, pp. 1–4.

Jerrold Post, as quoted in Benedict Carey (2011) “Teasing Out Policy Insight from a Character Profile,” The New York Times, March 28, 2011.

Farwell, J. (2014) “The Media Strategy of ISIS”. Survival: Global Politics and Strategies.

Awan, I., & Blakemore, B. (2012) Policing cyber hate, cyber threats and cyber terrorism. London: Ashgate Publishing.

Klausen, J., Barbieri, E., Zelin, A., & Reichlin-Melnick, A. (2012) The YouTube jihadists: a social network analysis of Al-Muhajiroun’s YouTube propaganda campaign. Perspectives on Terrorism, 6(1).

Al Hayat Media Centre (2014) There’s no life without Jihad. YouTube, June 19, 2014. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sFltVWWBUYE

Franz, A. & Shubert, A. (2015) “From Scottish teen to ISIS bride and recruiter: the Aqsa Mahmood story”. CNN.

Petrou, M. (2015) “‘Teen girl jihadists’”. Maclean’s. 128, 10: pp. 28-30.

Gorman, Siobhan (2009) Electricity Grid in U.S. Penetrated By Spies. The Wall Street Journal. 8 April, 2009.

GitHub: scada-tools [1] (2017)

Sanger, David E.; Broad, William J. (2017) “Trump Inherits a Secret Cyberwar Against North Korean Missiles”. The New York Times. 4 March 2017.

Amy Castor (2017) “A Short Guide to Bitcoin Forks”. CoinDesk. 27 March, 2017.

Roose, Kevin (2013) “Inside the Bitcoin Bubble: BitInstant’s CEO – Daily Intelligencer”.

Faiola, Anthony; Farnam, T.W. (2013) “The rise of the bitcoin: Virtual gold or cyber-bubble?”. Washington Post, 4 April, 2013.

Lee, Timothy (2013) “New Money Laundering Guidelines Are A Positive Sign For Bitcoin”. Forbes. 19 March, 2013.

Lachow, I., & Richardson, C. (2007) Terrorist use of the internet: the real story. JFQ: Joint Force Quarterly, 45, pp. 100–103.

Federal Aviation Authority (2017) “Satellite Navigation – GBAS – How It Works”. Available at www.FAA.gov.

Care, Susan (2016) Delta Meltdown reflects problems with aging technology. Wall Street Journal, August 8, 2016.

Powell, Sebastian, South West Airlines is recovering from the worst outage in company history (2016) Loyaltylobby, July 27, 2016.

Kaplan, A., & Haenlein, M. (2010) Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53(1), pp 59–68.

Schmid, A. (2005) Terrorism as psychological warfare. Democracy and Security, 1(2), p. 138.

Krasnova, H., Spiekermann, S., Koroleva, K., & Hildebrand, T. (2010) Online social networks: why we disclose. Journal of Information Technology, 25(2), pp. 109– 125.

Wright, Shaun; Denney, David; Pinkerton, Alasdair; Jansen, Vincent A.A.; Bryden, John (2016). “Resurgent Insurgents: Quantitative Research Into Jihadists Who Get Suspended but Return on Twitter”. Journal of Terrorism Research. 7 (2), 17 May, 2016.

Desmond, P. (2002) Thwarting cyberterrorism. Network World., 19(7), pp. 71–74.

Krasnova, H., & Veltri, N. F. (2011) Behind the curtains of privacy calculus on social networking sites: The study of Germany and the USA. Wirtschaftsinformatik Proceedings 2011, Paper 26.

Krasnova, H., Veltri, N. F., & Günther, O. (2012) Self-disclosure and privacy calculus on social networking sites: the role of culture. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 4(3), pp. 127–135.

Khan, I. (2013) A Human Rights Agenda for Global Security. In Cahill K. (Ed.), History and Hope: The International Humanitarian Reader (pp. 111-123). Fordham University Press.

Awan, I. (2013) Debating the meaning of cyber terrorism: issues and problems. Internet journal of criminology.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (1988) Recommendations of the Council concerning guidelines governing the protection of privacy and trans-border flows of personal data.

OECD (2002) Guidelines for the Security of Information Systems and Networks: Towards a Culture of Security (25 July 2002)

Katsicas, Sokratis K. (2009) “35”. In Vacca, John. Computer and Information Security Handbook. Morgan Kaufmann Publications. Elsevier Inc. pp. 1-606.

References

1. Early reports indicate that Saipov was “self-radicalized”. John Miller, of the New York Police Department, said that Saipov unleashed terror on lower Manhattan following ISIS` social media counsel on how to carry out vehicular attacks.

2. Asymmetric warfare involves surprise attacks by small, simply armed groups on states armed to the teeth with modern high-tech weaponry.

3. The word `wolf` is a misnomer. Let us not degrade wolves, who are such mercurial and majestic creatures. These perpetrators should be labeled “Lone Offenders”.

4. Acid attacks, once primarily confined to developing countries, have become frightfully common in the West, alarmingly so in the United Kingdom in 2017, especially targeted against Muslims.

5. On the Nice attacks see Khalid, Ozer (2016) Nightmare in Nice, The News International, Jang Group, July 18, 2016 and the article can be accessed at https:// thenews.com.pk/print/135665-Nightmare-in-Nice

6. On London`s Westminster bridge attacks consult Khalid, Ozer (2017) Blood and bravery in London, March 27, 2017, The Exppress Tribune, part of the International Herald Tribune, March 27, 2017. The riveting piece can be reviewed at https://tribune.com.pk/story/1366325/blood-bravery-london/

7. The author purposely caveats the word Jihad with “so-called” as he firmly believes that the word Jihad has been distorted and de-contextualized from its original meaning which implies an internal lifelong struggle for spiritual renewal and self-actualization. The way some counter terrorists currently use the word Jihad is a willful corruption of religious and cultural misappropriation. Michel Foucault correctly asserted that words, language and lexicon matter and those who control the lexicon control the narrative. Excellently explore Foucault in Foucault, Michel (1972) The Archeology of Knowledge & The Discourse on Language. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972. As well as Foucault, Michel (1977) “What Is an Author” Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews. Ed. Donald F. Bouchard. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977. Pp. 114-37. On cultural misappropriation view: Nouriani, D. Steven (Winter 2011) “The Defensive Misappropriation and Corruption of Cultural Symbols”. Jung Journal: Culture and Psyche. 5 (1): 19–30.

8. Nosferatu refers to “vampire” starring Max Schreck as the vampire Count Orlok (Dracula) in the seminal German expressionist Murnau`s film released in 1922, an adaptation of the brilliant Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) novel. For more: Mückenberger, Christiane (1993), “Nosferatu”, in Dahlke, Günther; Karl, Günter, Deutsche Spielfilme von den Anfängen bis 1933 (in German), Berlin: Henschel Verlag, pp. 69-72.

9. The term soft power was coined by Nye, Joseph (2004) in “Soft Power and American Foreign Policy.” Political Science Quarterly2 (2004): pp. 255-70.

10. The 2017 Battle of Raqqa was the fifth and final phase of the Raqqa campaign spearheaded by the U.S. bank-rolled Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) against IS, reinforced by airstrikes and SDF ground troops, titled the “Great Battle” taking place concurrently with the Battle of Mosul, as part of the CJTF–OIR to dismantle its structure strip IS of its regional centers of power and territory. For more: Damien Gayle (14 October 2017). «Last Isis fighters in Raqqa broker deal to leave Syrian city – local official». The Guardian and “Raqqa’s Al Naim roundabout liberated, 37 ISIS members surrender”. Hawar News Agency. 16 October (2017).

11. “US expands air base in northern Syria for use in battle for Raqqa”. Stars and Stripes. 3 April 2017.

12. Al-Masri was IS`s Minister of War and presented strategic advice on the Majlis al-Shura (consultation council) of IS. This work, titled ‘Message on the Manhaj’ (‘Manhaj’ refers to direction/vision), which was disapproved by senior rank and file, his books were censored. Al-Masri vanished, and was most likely arrested by IS` heavy-handed security apparatchik. Al-Masri`s role in birthing a council that played a part in organizing the Hisba (Islamic morality enforcement) and Zakat (Alms giving) bureaucracies was not viewed very favorably. For more on dissent within IS` upper echelons review: Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi (2016) “Dissent in the Islamic State’s Yemen Affiliates: Documents, Translation & Analysis,” Combatting Terrorism Center (CTC) and also Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi (2016) “Dissent in the Islamic State: Abu Al-Faruq Al-Masri’s Meesgae on the Manhaj: Documents, Translation & Analysis,” Combating Terrorism Center (CTC) 2016.