by Ozer Khalid*

*The author is a Senior Consultant, geo-strategist, a regular CQ contributor and a counter terrorism expert and can be reached at [email protected] and tweets @OzerKhalid

Abstract

This CQ study examines how the Taliban illicitly profit from narcotics, despite their declaratory rhetoric and researches how traffickers influence the strategic goals of the Taliban. In addition, it examines the covert reasons behind why the Taliban actually banned poppy cultivation on 3 April 2022 and uncovers the banned policy’s true motives and implications for an increasingly fragile narco-state with a crippled economy. This document also observes how, with the ban of poppy, more traffickers are turning to methamphetamine which ends up in Europe.

This CQ analysis explores the major regional supply chains, trade and smuggling routes through which these illicit substances reach far- flung areas of our increasingly inter-connected and vulnerable world. Recommendations are offered with a view to making Afghanistan and the Afghans less reliant on narcotics and more on alternative viable economic activities and wider-ranging reforms – Author.

Situational Context

Opium poppy and other nefarious narco-crops have been cultivated in China, Southeast Asia and especially in Afghanistan for over two centuries. The mature plant produces a highly addictive latex which may be refined to produce opium, or treated with highly lethal and addictive chemicals to produce morphine (pain-killer) or heroin.

This is especially the case in Afghanistan’s poppy-rich violence wracked south and southwest, where an underground informal economy intersects with radicalized extremism, largely fuelled by a thriving opium, heroin and methamphetamine trade. Most of the drugs produced are exported to the world’s unlawful black markets.

The United Nations and America maintain that the Taliban profit from and are involved in all facets of the drug supply chain, from poppy planting, opium extraction, and trafficking to exacting “taxes” from cultivators and drug labs to charging smugglers fees for shipments bound for South Asia, Africa, Europe, Canada, Russia, the Middle East and beyond.

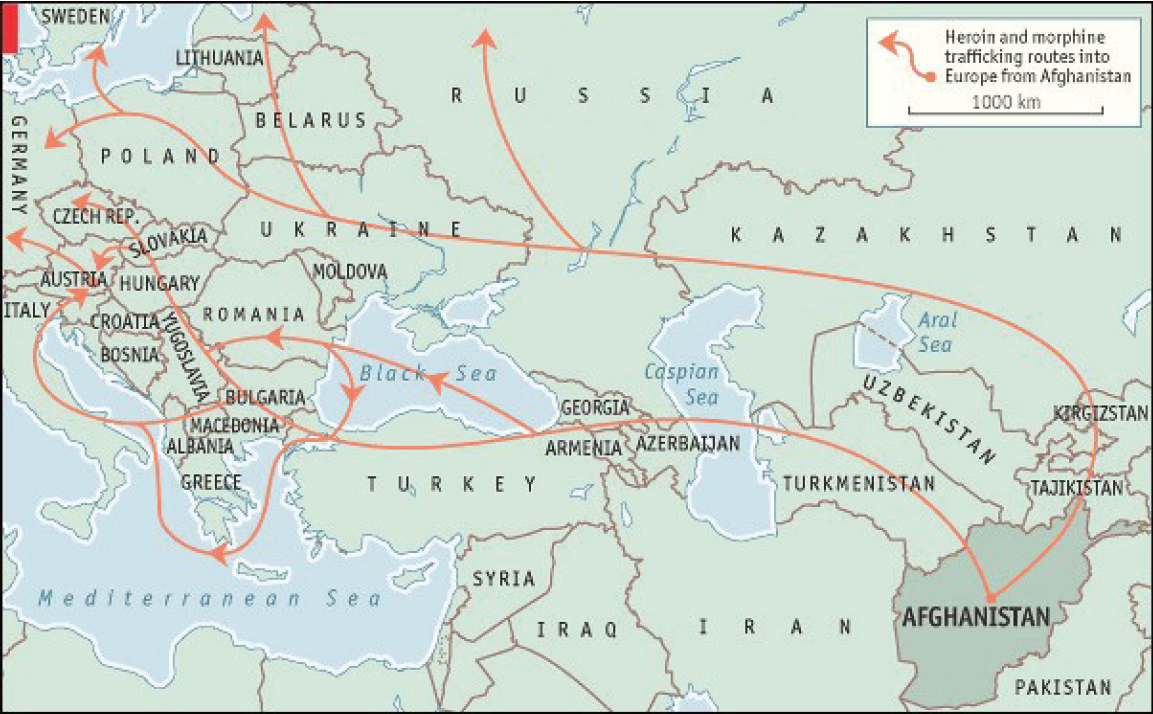

The illicit drug trade in Afghanistan is a rising concern not only for regional countries, including Pakistan, Iran, Turkey and Russia, but also for the wider region and Europe, as a gigantic majority of the heroin on European streets originates in Afghanistan.

Zabihullah Mujahid, at a press conference in Kabul, confirmed that the Taliban, on 3 April 2022, imposed a prohibition on poppy cultivation, trafficking and the use of illicit drugs. Despite this official announcement, empirical evidence highlights increasing drug production in Afghanistan this planting season, the same rings true for trafficking, which is booming along multiple well-established trafficking highways such as the Southern and Balkan-Route through Pakistan, Iran and Turkey to Europe.

Opium cultivation will carry on but now more discretely under the radar. David Mansfield1, a prolific researcher on illicit economies, confirmed that huge drug seizures in regional neighbouring states suggest the trade is alive and kicking.

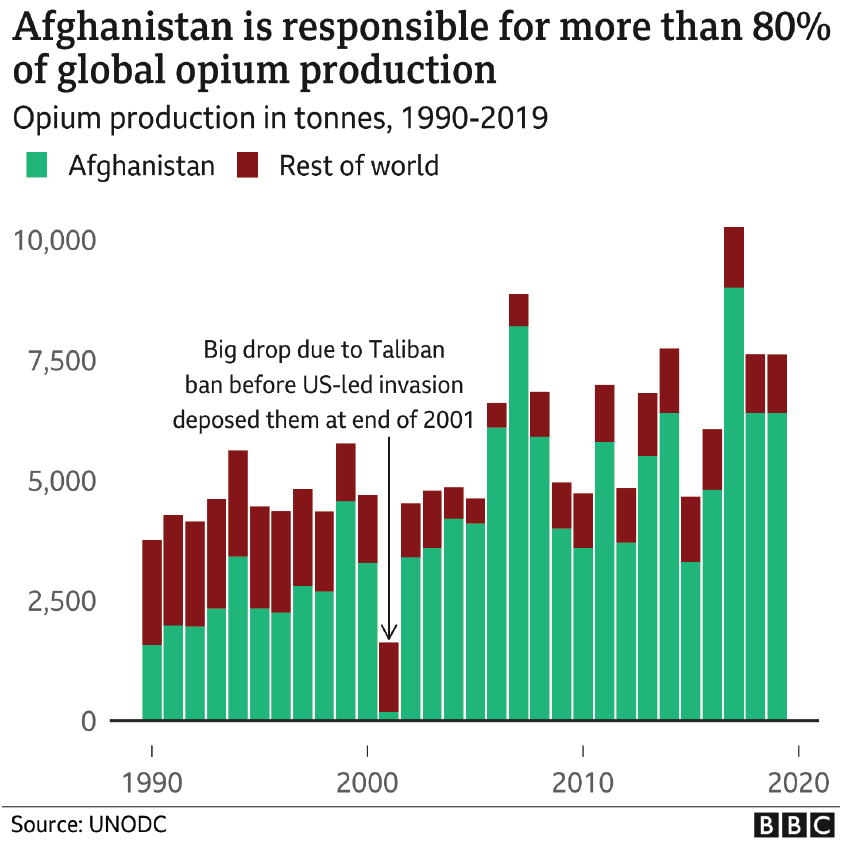

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) confirmed in February 2022 that opium production in Afghanistan increased by 8 percent in 2021, even though the surface area under poppy cultivation withered.

Reports of the chopping of pomegranate trees, a long-term productive asset in the Arghandab, and their replacement with poppy illustrates rising stress levels even in more well-off locations, and signals the potential for much higher levels of discrete under-the-radar poppy cultivation further into 2022.

In spite of the ban, trafficking from Afghanistan soars, proven by large, frequent seizures, especially along the Balkan Route used to smuggle Afghan drugs through Iran and Turkey to Europe, and Southern Route, via Pakistan and the Indian Ocean.

Ban or no ban, illicit drugs are an economic lifeline for many Afghans as the fragile state collapses like a house of cards into a frantic humanitarian crisis following the culmination of the NATO war and withdrawal of foreign aid, compounded by crippling sanctions.

Now that the poppy cultivation ban has come into force, the Taliban have to tread carefully to avoid alienating their rural constituencies and not provoking resistance and violent rebellion. In rural Afghanistan power is negotiated and the rural population is an essential political constituency the Taliban cannot afford to ignore. Conflict, closed borders and drought have impacted the few legal alternative profitable crops that provided opportunities for farmers in the past.

The panacea to Afghanistan’s looming drug crisis is not prohibition per se, but long-term socio-economic development that empowers Afghans with realistic opportunities other than drug production and trafficking. The UN, donors and the international community should furnish aid and funds to urgently facilitate this outcome2.

Afghanistan – A Narco-State in Crisis

Amidst desperate circumstances, with droughts hindering wheat cultivation, farmers have scant choice but to grow opium, which requires less water than legal crops and can still be trafficked out of the country, even if borders are closed.

After decades of internecine wars and fighting Afghanistan, Asia’s poorest country, is sanctioned and its asset are frozen, making it more cash-strapped and insecure than ever before, thereby, it has become an ideal location to grow opium. Poppy cultivation is also more cost- effective and easier than growing wheat, which is how a majority of Afghans made a living before the opium industry started thriving in the 80s. As per the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) by mid-2022, 97% of Afghans could fall under the poverty threshold3, which would further plunge the country into a catastrophic humanitarian crisis, rendering many more dependent to the life-threatening poppy and opium cash crops.

According to the UNODC, the total revenue generated from illicit opiate business only inside Afghanistan was between $1.8 billion and $2.7 billion in 2021. A lion’s share of the profit went to stakeholders who controlled global supply chains. These stakeholders are now the Taliban themselves, along with their foreign allies. “The Taliban have counted on the Afghan opium trade as one of their main sources of income,” declared César Guedes, head of UNODC’s Kabul office.

Afghanistan is the world’s largest producer of opium, according to UNODC. Its opium harvest accounts for more than 80% of the world’s supply.

Ever since the 2001 American invasion of Afghanistan, poppy trade has played an instrumental role in destabilizing not just Afghanistan but also its neighbouring countries.

America allocated north of USD 8 billion over 15 years to eliminate Afghanistan’s poppy industry and deny the Taliban and associated militants a lion’s share of financing. The grandiose plan, inter alia, featured airstrikes and laboratory raids. Yet, such initiatives remained unsuccessful. In 2017 UNODC valued the overall size of its opiate business to be USD 6.6 billion, equivalent to 30 percent of Afghanistan’s Gross Domestic Product4.

U.N. officials reported that the Taliban likely earned more than $400 million between 2018 and 2019 from drug trade. A May 2021 U.S. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan (SIGAR) report quoted a U.S. official as estimating that the Taliban derive up to 60%5 of their annual revenue from illicit narcotics.

Despite April’s declaratory opium ban and the Taliban’s pledge to patrol and protect their borders to prevent narco-trafficking, in reality they chose to overlook smuggling activities, knowing that a lot of those funds would be indirectly transferred back into their own coffers.

Narco-trafficking, as a problem, does not haunt Afghanistan alone. Anti-state entities the world over exhibit criminal patterns of behavior. The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in a now highly unstable Sri Lanka, the now moribund Irish Republican Army, etc., had all profited from drug smuggling in their respective geographies, and their involvement in crime skewed the aspirations of their movements over time.

Pakistan is especially susceptible to narcotics and terrorist infiltration through Afghanistan. As if the increasing inflow of drugs and the Taliban destroying the border fence in January 2022 with Pakistan was not enough, terrorism is markedly on the rise. In 2022 Afghanistan–Pakistan border skirmishes enabled terrorists like the Tehrik-i-Taliban (TTP) based in Afghanistan to cross into the Kurram District and attack a Pakistani Army checkpoint on the Durand Line, killing five Pakistani soldiers6. This was one of many cross-border terrorist tragedies.

The Taliban: Narcotics and Networks

Many Taliban commanders and their extended networks at the rural village level widened their drug related activities through extortion and levying protection fees on heroin refineries (mostly in Southern Helmand, Kandahar and Farah7 provinces). Taliban (provincial) commanders and other terrorists engage in kidnapping and other smuggling schemes8.

Old habits die hard. As Taliban commanders have historically been tied to drug related criminal activity, in the future they are likelier to carry on such nefarious activities under different brand names, guises and splinter groups and, if not overtly participating, are likely to “look the other way” when it comes to narco-trafficking and profiteering.

Although there has always been a wide variation across the war theater, drug profits travel up the chain of Taliban command and other insurgent and extremist organizations operating along the Afghanistan- Pakistan border, such as the Al-Qaeda, ISKP Khorasan Province and the TTP. Drug money still appears to play a prominent role in funding the operational costs of the Taliban (more covertly now that they are in government as compared to earlier on) and other terrorist cells and outfits.

In order to disrupt these drug profits intelligence “assets” need to penetrate and break up powerful drug cartels that fund extremism, launder illicit money and ruin lives through crippling substance abuse and addiction. Predictably, most smuggling networks appear to be run by close-knit families and tribes, making them impenetrable. They appear to work with terrorists and corrupt state actors (often from within the Taliban too). Their intent is pure profit, using religion and politics as a pretext and ideological cover.

The Holy Men of Heroin

Taliban’s Drug Policy – Rhetoric versus reality

When the Taliban government pledged to halt the world’s largest opium and heroin supply, it made the international headlines. Was this the state’s attempt at seeking an alternative path to international diplomatic recognition and humanitarian relief?

The Taliban, thirsting for a seat at the UN, global diplomatic credentials and recognition and in desperate need of funds and assistance, may have considered such a ban on opium poppy across Afghanistan as a much-needed, well-timed publicity stunt to achieve some of its goals. Predictably, the ban has not had the intended effects.

This ban did enthrall many observers. Why forbid a highly profitable drought-resistant crop just as Afghanistan’s economy is on a knife’s edge, without global pressure or international diplomatic and financial guarantees? There are many reasons to remain skeptical of the Taliban’s rhetoric. Even though its earlier (2000) ban on poppy cultivation was extraordinarily effective, stirring a 75 % reduction9 in the global heroin supply – the moratorium was too short-lived (lasting only from July 2000 to October 2001) to draw substantive conclusions regarding its long-term potential, including whether the ban would gain sustained political buy-in10.

The Taliban’s motives in July 2000 were equally questionable. Reprieve from global isolation and sanctions was also the intention back in 2000. Market forces were another, as opium and heroin prices soared in the aftermath of a supply glut, exponentially raising the taxes the Taliban reportedly still collected. Yet, farmers in the Taliban’s southern hinterland were visibly dissatisfied, and enforcement faded prior to the October 2001 NATO invasion. Following the Taliban’s eclipse from power after the U.S. invasion in 2001, the former, backed up by local Afghan farmers, ratcheted up poppy cultivation to fund their own war chest.

The subsequent insurgency reshaped the Taliban’s rapport with opium and heroin. Although Taliban’s top brass maintained safe havens outside their borders and received funding from elsewhere, it was insufficient to sustain a two-decade long war against the US and the republic it backed. The lucrative drug trade helped plug that fi gap.

The Taliban’s Holy Men of Heroin benefited mainly by levying opium taxes on farmers, laboratories, traffickers and other nefarious actors. Applying Islamic taxes on poppy cultivation resulted in huge revenues, ranging from USD 200 to 400 million annually and also offered them a religious cover and justification. By green-lighting poppy cultivation in locations under their control, the Taliban also won the support of southern farmers who resisted global pressure to abandon a lucrative crop.

Opium poppy is quintessential to Afghanistan`s economy. Even prior to the Taliban’s August 2021 power grab, unemployment, corruption, drought and COVID-19 had wrecked rural and urban economies. Water shortages obliterated staples like wheat and corn. A crop that requires very little water, poppy cultivation rose by 37% in 2020, as per UNODC. The poppy’s resilience amid adversarial agricultural realities renders it an attractive long-term investment. In 2021, Afghanistan’s illicit opiate11 economy’s gross output was forecasted at between USD 1.8 and USD 2.7 billion, a 12 % hike from 2020 and representing a stunning 9 to 14% cent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product12.

Opium trade is a convenient business for many reasons. War-lords and traffickers lend money to farmers to harvest poppy and collect the opium paste directly from them. Poppy cultivation offers easy access to credit13 and quick sales, circumventing the risks of transporting the crop to market. It also provides tenant farmers access to land and daily-wage labourers’ substantial opportunities during harvest seasons. Disrupting this business model, for a regime that is patently aware of the risks, requires pre-calculated intent and deliberation. The April 3rd ban was time-sensitive and pre-meditated.

Global Diplomatic Recognition

Until Russia’s war in Ukraine, Afghanistan was the major foreign- policy story. After the Taliban’s August 2021 takeover, governments, INGOs and the commentariat were clamoring to devise methods to protect Afghans from starvation without conducting direct business with the regime. A global consensus was emerging in the policy circles that the US should loosen its sanctions grip and unfreeze the USD 9.8 billion Afghan central bank foreign reserves14, even if this benefited a ‘rogue’ regime in Kabul. Although the Taliban was still short of diplomatic recognition, and despite multiple hiccups, it seemed to be inching ever closer towards global engagement.

However the Russia Ukraine war has diluted resources and political capital that Western governments were willing to expend on Afghanistan. Even substantial events like the U.S. Treasury’s 25 February General License 2015, issued the day after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, passed with scant commentary or critique. This licence allows for most business transactions that do not involve direct transfers to the Taliban, their Haqqani Network allies, or other UN proscribed individuals (or entities they own), to be carried out without most legal impediments. Yet, Afghanistan’s banks are still not integrated into the global banking system, and the financial sector and formal economy remain shattered and fragmented.

Taliban`s regional diplomatic recognition and economic lifeline requires preserving the Taliban’s income from trade with neighbouring Pakistan, China, Iran and Central Asia which has brought the Taliban hundreds of millions in informal taxes. This is largely contingent upon whether the Taliban can assure Pakistan’s (TTP), Iran’s, Russia’s (Chechens), Uzbekistan’s (Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan) and China’s (ETIM, Turkistan Islamic Party) principal counter-terrorism interests and prevent the leakage of terrorism to trickle over into these countries and Central Asia. The results so far are lacklustre (especially in Pakistan and Iran where terrorism from Afghanistan’s sanctuaries have grown). Counter-terrorism requirements for these countries trump any economic opportunities Afghanistan offers. And with the exception of China and the Gulf countries, their aid pockets are shallow.

The Biden administration has, however, pledged funds to support the people of Afghanistan. The U.S. Treasury and multilateral development banks, including the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, offered economic succor to the Afghan people. In January 2022, the administration announced $308 million in USAID humanitarian assistance for Afghanistan, with a focus on Afghan refugees.

In December 2021, the US, and the World Bank-run Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund transferred $280 million to UNICEF ($100 million) and the World Food Programme ($180 million). This enabled UNICEF to provide essential health services to 12.5 million people (including 1 million vaccinations), and allowed the World Food Programme to provide food assistance to 2.7 million Afghans. This amount brought the grand total to approximately $1.75 billion in support from multilateral development banks to meet critical basic human needs of the Afghan people.

Despite such funding, the Taliban regime is economically stung by the loss of billions dollars that were allocated to Afghanistan—from the IMF, the World Bank, the United States, and the European Union; as the country’s central bank reserves are frozen by America and half of the USD 9.8 billion is being donated to victims of 9/11.

Afghanistan`s illegal and informal economies can only offset a part of those central bank reserve losses. Banning poppy cultivation, to make good on its promise of a “drug-free” Afghanistan is socially explosive. Over the short-run, maintaining any such blanket ban necessitates extensive heavy-handed enforcement repression.

However, the largest blow to the Taliban’s attempt for global legitimacy was a self-inflicted wound. Less than seven days after the UN Security Council voted to extend the UN’s political mission in Afghanistan, the Taliban turned its back on a prior commitment to allow secondary education for girls16. The global community was rightfully outraged and America annulled a meeting in March 2022 with the Taliban in Doha.

If aspirations for Afghan girls and women to live a life of dignity and equality under the Taliban are waning, then so too is the likelihood of deeper diplomatic interaction. Hence, the opium ban is an attempt to salvage a dire diplomatic fracas, channelling the global spotlight to what, in the Taliban’s worldview, should be a more pragmatic apprehension. Irrespective, the global community must continue to protect the inalienable rights of Afghan women and girls who, at present, are robbed of hope by Taliban 2.0.

Delivering on its declared promise to rid Afghanistan of poppy will be very difficult for the Taliban. In a fragile state where ninety percent of people live in poverty and at least twelve million suffer malnutrition, such a ban would also exclude income and employment for the Taliban’s middle-tier commanders and rank-and-file soldiers, thereby, exacerbating divisions and fissures within the Taliban’s chain of command. Rising dissatisfaction of the Taliban’s mighty middle- layer commanders and their networks poses a genuine challenge for the Taliban.

Many practitioners cast doubts over the Taliban’s ability to strictly control the drug trade. “They can’t stop it, Many Afghans depend on drugs for their livelihood” and lack economic substitutes17.

However, while smuggling continues, the Taliban have cracked down on domestic drug use. Addicts have been rounded up, beaten or doused with water and forced into rehabilitation centres. This is a déjà vu of the 1990s, when the Taliban accommodated production and trafficking but were harsh towards users18.

Drugs, Opium Bans and the Taliban`s Chain of Command – Long term survival

The Taliban has reportedly created an anti-trafficking force in Badakhshan province near the Tajik border with aspirations to mollify Russia and appease China19. The Taliban is keen to forge closer ties to Moscow and Beijing (for precipitating their diplomatic recognition). Both China and Russia expressed concern about drug-trafficking from Afghanistan, although drug-trafficking to China is more from the Golden Triangle.

Taliban’s success as an insurgency reflected the reality that in spite of consistent NATO efforts to ignite internal fragmentation, the group remained internally cohesive. But the challenge of preserving cohesiveness across its various wings and factions, having varied ideological intensity and material interests is very different in war than it is now that the Taliban is in power.

Various Taliban factions have highly diverse views about how the new regime should rule across nearly every dimension of governance – from inclusiveness, to tackling foreign fighters, to the economy, to external public relations. Many of the middle-level battlefield commanders— younger, more plugged into global networks (including drugs), and without the same personal experience of the Taliban mismanaging its 1990s rule—are more hard-line than some elder top Taliban leaders and shadow governors20.

To survive long-term as a regime, the Taliban will not only need to bridge and manage their different views on governance but will also need to assure that key commanders and their rank-and-file soldiers retain ample income so that they are not tempted to defect to ISKP, al- Qaeda or other extremist entities. A poppy ban significantly constrains the pool of resources to keep the multiple Taliban elements content21.

A key to the Taliban’s successful blitzkrieg in August 2021 was its bargaining leverage with local, provincial and national level powerbrokers and militias that the Taliban would allow them to maintain certain rents from some local economies, such as mining in Badakhshan, logging in Kunar and the drug trade in Helmand, Farah and across the country22.

It still remains to be seen whether the Taliban’s top or local brass will get greedy and default on those promises, seeking instead to dislocate non-Taliban political and criminal structures from the drug trade and other local economies. A Taliban move to exclude others from local rents (especially drugs) would be a replay of the behavior of anti- Taliban warlords post-2001, but it would once again yield new causes for friction amidst a tanking Afghan economy and potential bases of armed opposition.

The April poppy ban will disappoint the Taliban. Anti-narcotics collaboration are a low priority even for Western governments like the United Kingdom23 which must contend with heroin from Afghanistan ending up on Western streets24. Their anti-narcotics operations strategies during the days of the corrupt Afghan republic were fruitless, much before the Taliban took the reins of power in Kabul. With the Taliban now at the helm, UNODC, the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)25 and other agencies’ footprint in Afghanistan will be minimal. Global plans to stem the flow of Afghan narcotics will have to rely on interdiction and interception, in partnership with transit nation-states such as Pakistan and Turkey.

Geopolitical and economic implications of the Taliban’s poppy ban

Who will bear the brunt of the ban? Based on past history and precedent, limiting narcotics trade can offer the Taliban’s armed rivals (ISKP, Al-Qaeda) with similar opportunities to exploit rural grievances that abolition endeavours under the republic gave the Taliban insurgency.

The southern provinces of Helmand and Kandahar are the lifeline of the Taliban movement and poppy production26. Yet cultivation has incrementally now grown in Northern provinces too, where Taliban’s opposition wield some influence. Cultivation is booming in areas where the crop barely grew, like the northern provinces of Jowzjan and Balkh, whose capital Mazar-i-Sharif sees pink poppy flowers bloom27 with spectacular growth rates since 2017.

The southern opium crop growth cycle commences in March and April, but the farther north one goes, the later it begins. By the time the regime starts “enforcing” the ban, it is likeliest to affect only the Northern provinces harvest. Any future headlines and soundbites praising action against poppy farmers should be read between the lines and within context – as the Taliban’s flexing its muscles in the north.

Selective enforcement of the opium ban (which is likely) will benefit Taliban allies in the south. Market saturation reduced opium prices in 2021, however, the price28 of heroin is very elastic29 and rose when neighbours such as Pakistan and Iran closed or tightened their borders with Afghanistan post-August 2021, and cultivation receded.

After the declaration of the ban the price 30 of opium in Kabul rose by a multiple of eight as dealers opportunistically foresaw disruptions to the northern harvest. Price fluctuations and volatility must be monitored in Afghanistan and Western economies31 to assess the ban’s supply impact.

The 2000 prohibition on poppy cultivation was enforced to a large extent. This may persuade many analysts now to take the new prohibition seriously and deem it a substantial measure. However, for Western governments, it will not eclipse the Taliban’s dismal track- record on women’s and human rights. And like similar relatively positive measures enacted by the Taliban, this ban too can eventually witness a reversal.

Pakistan’s Narcotics Challenge from Afghanistan

Pakistan is the state that is most inundated with and devastated by the flood of cross-border narcotics from Afghanistan. Opium, heroine and other illicit substances seep into Pakistan mainly through the Southern Route, a long porous 2,670 km border between Pakistan and Afghanistan (the Durand Line). Although the new border fence infrastructure makes smuggling tougher along the frontier32. The nearly 2,600 km border fence sparked protests from Kabul and was damaged by the Afghan government.

Smuggling and trafficking into Pakistan also occurs through the Afghan border crossings in Spin Boldak, in the southern Afghan province of Kandahar (a major drugs den) and mostly through the Torkhum border in the eastern Afghan province of Nangarhar from where they find entry points in KP.

These narcotics are often further smuggled out of Pakistan through the Pak-Iran border of Mirjaveh and Taftan as well as the Pishin Mand into the entry point of Baluchistan border by road. Trafficking also occurs via the lengthy Makran coast or by sea and air.

Despite the fence a “huge quantity of drugs is reaching the coastal belt of Balochistan and Karachi.” The law-enforcement capabilities in Balochistan province are weaker than in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa33.

The direct destinations for these drugs are Iran, Kashmir and China. The indirect destinations include Southeast Asia, Africa, the cash-rich Gulf states and Europe.

Multiple Pakistani entities and law enforcement agencies have counter-narcotics mandates. The major stakeholders include: the Anti- Narcotics Force (ANF)34, the Ministry for Narcotics Control (MNC)35, KP, Punjab and Sindh rangers, Pakistan customs and the Pakistan Coast Guard (whose role augments in drug seizures, especially given the recent increase in maritime drug trafficking). These organizations have adopted a well-known “zero-tolerance” policy, especially relating to poppy cultivation.

Pakistan’s Illicit Narcotics – the Patients, the Players, the Policies and Programmes

The Players:

The contraband smuggling and trafficking actors are: tribal dons and underworld “bosses” who distribute and sell the product at handsome margins; corrupt bribe-taking customs and enforcement agents; poor farmers and addicts who also play a large role in transporting and storing the drugs; and drug dealers who supply and distribute the merchandize to retail customers.

Although Afghanistan is dubbed as the “Colombia of Central Asia”, South and Central Asian drug markets offer distinct features from their South American equivalent. They are not organised as “mega-cartels” with the power of small states. They are smaller and more fragmented, disparate criminal networks. These groups are able to extend their regional influence because of lackluster border security, limited transnational cooperation, and widespread corruption among law enforcement and local customs/police officials.

Policies and Programs:

Mounting violence, poverty, uncertainty and a humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan has intensified cross-border narco-trafficking and exacerbated Pakistan’s domestic drug problems.

In addition to Pakistan’s strict ‘zero tolerance to poppy cultivation program’ Pakistan is an active member of the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) and the ANF and other agencies provide timely intelligence and data to UNODC.

ANF’s concerted counter-narcotics endeavours led to record-high drug seizures in 2020 and 2021, bearing an impact far beyond Pakistan’s borders. Such successes have been supported with capacity-building initiatives by the UNODC, in order to develop a safe community free from the hazards of drug trafficking and related transnational organized crime.

With the ongoing geopolitical situation in Afghanistan, there is a requirement for consistent capacity-building support to address the emerging risks more effectively (such as the Afghan-origin opiates, particularly New Psychotropic Substances (NPS) and synthetic drugs flowing into Pakistan). This will further stabilize peace and socio- economic development in Pakistan and the wider region36.

In February 2022 the Ministry of Narcotics Control, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) UNODC Country Office Pakistan (COPAK) and the Japanese Government enhanced the counter-narcotics capacity of the Anti-Narcotics Force (ANF) by donating and installing prefabricated buildings and body scanners to detect narcotics as part of the Border Security Project

The prefabricated buildings were installed in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province, as well as body scanners which were already operational at the Sialkot, Multan and Faisalabad International Airports. These facilities and equipment are offered to the ANF under the auspices of a UNODC funded project for ‘Strengthening border security against illicit drug trafficking and related transnational organized crime’ spanning from April 2016 – December 2021.37 “UNODC well recognizes ANF’s leading counter-narcotics role, and it will always remain our crucial partner in Pakistan38,39.

Pakistan’s ANF spearheads leading counter-narcotics efforts not only in Pakistan, but has also supported drug interdiction operations with international partners, through sharing of timely and accurate information. “The ANF has executed multiple drug interdiction operations to nab Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs) existing in South Asia that carry on willfully exploiting Pakistan’s sensitive and strategic geographical location next to Afghanistan and the shortest distance it provides to the international maritime routes”40.

On the social and development side, an active Drug Abuse and Awareness program led by the United Nations Association of Pakistan (UNAP) addresses a range of aspirations from lowering demand to a reduction of drug related crime and violence, and reduction of drug-related health and social costs. The goal of the UNAP’s Drug Abuse and Awareness Campaign is to educate and empower Pakistan’s youth to reject illicit drugs. This goal includes preventing drug use and encouraging occasional users to discontinue use.

UNAP’s Drug Abuse and Awareness policy also seeks to assist people to avoid or delay drug initiation and, if they have commenced, to avoid developing drug use disorders (episodes of violence, hostility when confronted about drug dependence, lack of self-control), facilitate behavioural changes and prevent negative social consequences of drug abuse41.

The Patients:

The War at Home: the Grim Reality of Drug Addiction in Pakistan

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Pakistan has 7 million drug users. Pakistan’s Anti-Narcotics Force estimates that out of these 4 million use cannabis while 2.7 million42 consume opioids43. More than 4 million of these are intense addicts, amongst the highest number for any country. Estimates are that more than 800,000 Pakistanis aged between 15 and 64 consume heroin frequently and regularly. It is also estimated that up to44 tons of processed heroin are consumed per annum in Pakistan. The population partaking in drug abuse is mostly of a lower income background.

Such alarmingly high figures for drug consumption are cause for genuine concern and often leads to an explosion of mental health crisis, which is woefully downplayed and stigmatized in Pakistan due to cultural norms. Mental health crisis’ result in drug use personality disorders, chronic depression, self-harm, crippling poverty, exasperatingly high suicide rates and other social ills.

Over the past few years, several rehabilitation and drug addict treatment centers have mushroomed, but much more can be done in this regard, especially in rural areas. To curb substance abuse several Model Drug Abuse Centers are rendering services in 10 hospitals across Punjab. There are six noteworthy centers in Lahore, including at the Mayo Hospital. Bridge Rehab Center and Nidaa clinic are other often cited centers that include alcohol treatment.

Some of the major addiction treatment centers in Islamabad include the Nishan Rehabilitation and addiction treatment center in Bani Gala, Addiction Intervention Online on Kaghan Road in F-8 and the IRC Islamabad Rehab clinic. In Karachi, the noteworthy Edhi Foundation offers addicts free rehabilitation service and runs six centres in Karachi with 4,500 patients receiving care, however rehabilitation cannot be left to philanthropy and goodwill alone.

UNPRECEDENTED SEIZURES

Drug-trafficking from Afghanistan is exponentially on the rise. The seizures are rising as Pakistan is burdened with huge quantities of narcotics.

There have been a spate of sizeable illicit drug seizures at Pakistan’s Torkhum border crossing with Afghanistan which increased substantively over the past few months44 to unprecedented levels. In December 2021 and January 2022, authorities at the Torkhum border post seized over 524 kg of hashish, 280 kg of opium, and almost 22 kg of methamphetamine. There have been unprecedented heroine hauls of 230 kg with some Afghan nationals taken into custody, according to data shared with TRT World by Pakistan Customs45.

On 7 March 2022, Pakistan’s Anti-Narcotics Force (ANF) organized an Inter-Agency Task Force (IATF) meeting to review the overall situation of the National Anti-Narcotics Policy. Pakistan’s ANF has also seized and intercepted large amounts of illicit substances, including 1,677.791 kg of drugs on 17 May 2022 and 793.206 Kg drugs and 1,086 Liters of highly dangerous Ketamine valued at USD 47.686 Million were seized in 44 operations from 11 to 20 February 202246,47.

The geopolitical situation in Afghanistan is “fluid” and the state is experiencing a “lot of challenges which is why such incidents are occurring48. The amount of heroin seized increased significantly from almost 14 tons to 20.5 tons in 2021, while 4.8 tons of meth were intercepted, up from about 4.2 tons the year before.

Recent years have witnessed joint shipments of Afghan heroin and meth travel through Pakistan or Iran by sea to Africa. Many often get interdicted. On 27 September 2021, for instance, international maritime forces intercepted two large consignments of drugs along the Southern Route in the Indian Ocean, where French Marine Nationale frigate FS Languedoc, operating in support of Combined Maritime Forces (CMF), seized USD 5.2 million worth of more than 3,600 kilograms of illegal drugs during a maritime counter- narcotics operation.

To quell this growing menace Pakistan participates in the Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) operations which regularly make narcotics seizures that largely originate from landlocked Afghanistan. Pakistan Navy’s long-range maritime patrol aircraft have undertaken over 130 sorties in CMF operations.

Nearly, 7,000 kilograms of hashish and 2 tons of cannabis resin have been confiscated by Pakistan Navy ships as part of CMF security operations. The frigate PNS Saif seized over 2,000 kilograms of hashish on the high seas on 29 January 2020. And on April 3 Pakistan Navy seized 100 kilograms of crystal meth considered a white narcotic (crystal Meth/ ICE) that was dumped at a location along the coastline near Ibrahim Hyderi area, Karachi.

Customs49 also often act on information tip-offs from Naval Intelligence to seize large quantities of crystal meth /ICE. Pakistani officials and law enforcement agents are highly cognizant that the issue of anti-narcotics cannot be divorced from money laundering and terror financing, since drug money often bankrolls extremist activities. This is particularly daunting for Pakistan given it’s grey-listing at the FATF and ensuing economic malaise. To highlight the overlaps between narcotics and terror financing, on 4 April 2022

Pakistan’s ANF organized a workshop50 at their academy on money laundering and terror financing.

According to the Financial Action Task Force, between 50-90% of all financial transactions in Afghanistan are conducted via money or value transfer services (MVTS)51. Illicit use of MVTS is key for opiate trafficking networks, not only in Afghanistan but globally.

Pakistan’s ANF and law enforcement agencies (LEAs) have made commendable strides to combat illicit drug trafficking and associated money laundering to contain the narcotics contagion. Ensuring stability and peace are central to realizing sustainable development in Pakistan.

Pakistan’s Future Online Drug Challenge – Technology and Web 3.0

One daunting challenge that Pakistan and other countries will face is how present and future drug traffickers and smugglers will use Web 3.0, blockchain and the dark web and other emerging tech platforms to misuse the internet for drug peddling and related money-laundering.

As tech platforms and Web 3.0 decentralize monitoring and tracing such illicit transactions will become more challenging, especially as drug related payments currently occur (and will increasingly do so) through hard to trace crypto-currencies. Russia’s Hydra Dark net drugs marketplace is but one example.

To mitigate this challenge Pakistan’s FIA Cyber Crime Unit and other similar regional Cyber Task Forces will need to be created, matured and work ever-closely with Interpol’s Cyber Crime Unit and the UNODC’s 2017 Global Program on Cybercrime with a view to:

- Increase efficiency in the investigation, prosecution and adjudication of cybercrime, especially narcotics trading, online child sexual exploitation and abuse

- Effective long-term whole-of-government response to cybercrime, including national coordination, data collection and effective legal frameworks, leading to a sustainable response and greater drug deterrence;

- Reinforce local, national and transnational online portals and communication between governments, law enforcement and the private sectors with broader public knowledge of cybercrime risks.

Russia’s Ukraine invasion and the drug trade

The Russian invasion and continued occupation of Ukraine complicates the emerging geopolitical Eurasian chessboard, not only by diverting scarce resources and policy attention away from global counter-narcotic measures but also by igniting social vacuums and a huge demand that multinational organized criminal syndicates and their state backers will not hesitate to fulfill52.

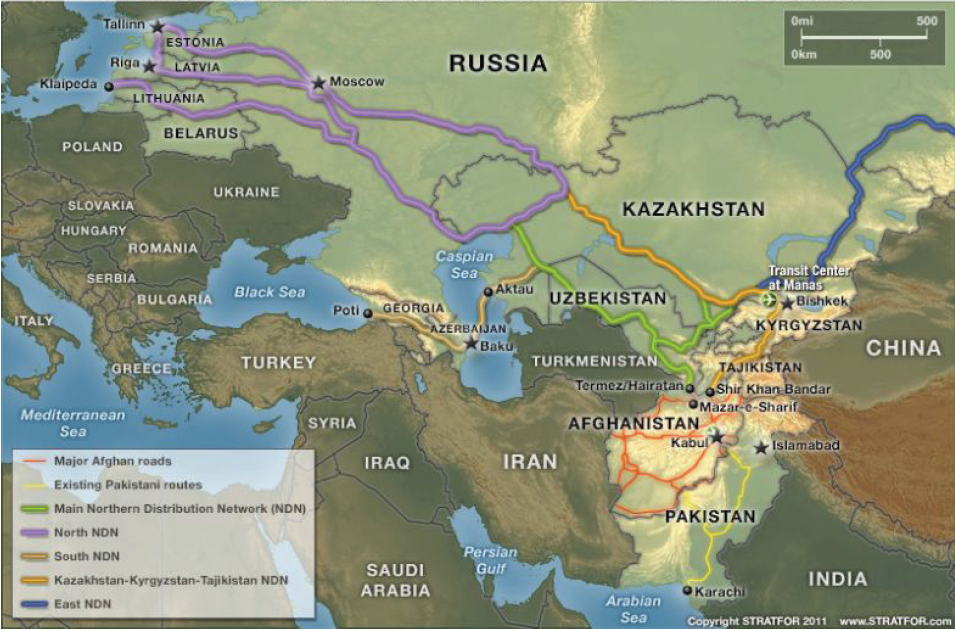

Drug trafficking in Russia is an old challenge. The radical rise of organised crime in the tumultuous years following the collapse of the Iron Curtain and the newly opened and poorly controlled borders with former Soviet states, spurred the transnational smuggling of opium produced in Afghanistan (which accounts for 90 per cent of the world’s heroin output). Travelling through the Northern route the drugs are smuggled to Russia through Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan.

The Afghan drug trade and it’s nefarious funds flowing across borders have inflicted Russia, Pakistan, South and Central Asia with conflict, corruption, and regional instability, while lining the pockets of terrorist organizations.

“The Afghan drug threat is one of the worst problems for Russia’s national security.”53 Accounting for one-fifth of the world’s opium market estimated at USD 65 billion54, Russia is the world’s largest heroin consumer, most of it is pouring in from Afghanistan via Central Asia.

Russia has six million addicts and an alarming drug-related mortality rate of 10.2 per 100,000 persons, far surpassing the rate of its EU neighbours. The UK, in spite of being Europe’s largest cocaine consumer, has a drug-related mortality rate of 3.7 per 100,000 persons. With a death toll of around 30,000 per year, Russia listed the drug trade as a major national security threat.

With a booming market largely driven by the rise of the Russian Hydra darknet55, the amount of synthetic drugs seized by Russian authorities multiplied twenty-fold over the 2008-2018 period. Hydra56 was a Russian-language dark web marketplace facilitating illegal drug trafficking and financial services such as bitcoin tumbling for money laundering and crypto currency-to-Russian-ruble exchange services and the sale of documents.

Regional cooperation has mostly emphasized short-term joint operations and border security, such as the International Anti-Drug Operation Spider Web in July 2019, which led to the seizure of 6,422 kg of narcotic drugs and 3,241 arrests. Though Spider Web`s 6,422 kg can be construed as a victory it is negligible compared to the hundreds of tonnes of heroin crossing the border each year.

Russia’s largely militarized and short-term strategy in anti-narcotics, both from Moscow and in its engagement with bordering states is imperative but insufficient.

Tackling the illicit drug trade will require a long-term strategy and a much greater political will to tackle its systemic root-causes. Fighting corruption, implementing institutional overhaul and offering economic benefits to the volatile region are as essential as border patrolling.

The Central Asian Powder Trails

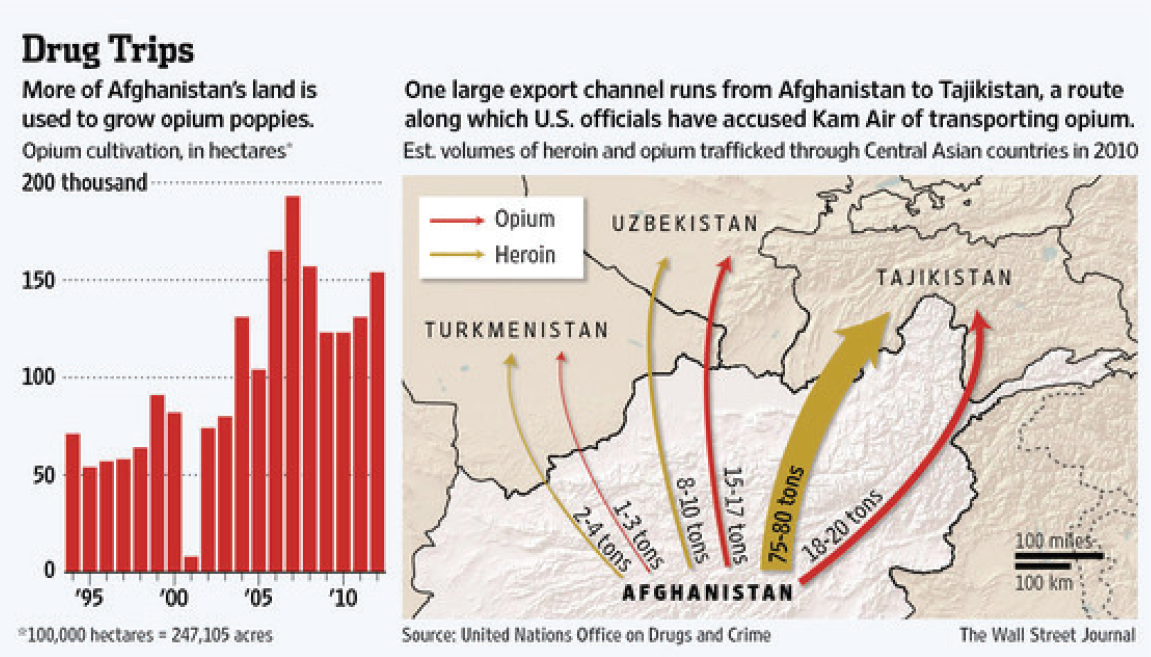

Opium, heroin and cannabis are produced and smuggled in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan— the last three share borders with Afghanistan.

Blaming porous borders and even the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU)/Greater Eurasian Partnership (GEP) which integrated Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan into a free trade zone with Russia in 2015, is exceedingly disingenuous. Although enhanced geo-economic connectivity and open borders make the region an idyllic transit route for illicit narcotics, it is complicity that less than five % per cent57 of the drugs transiting through Tajikistan are seized.

The widespread corruption and poverty afflicting Central Asian Republics like Tajikistan58 lead many to resort to drug trafficking. At present, the drug trade constitutes thirty per cent of Tajikistan’s GDP, with an increasing amount of people turning to drug trafficking to survive. Corrupt officials in Dushanbe are in on all of this at a high- level. Drugs are smuggled from Afghanistan into Tajikistan through the Southern border, funneled into Uzbekistan through the Western border, Kyrgyzstan via the North and China59 to the East. Afghanistan’s Wakhan corridor narrowly separates Tajikistan from Pakistan.

Source: Wall Street Journal and UNODC.

There are three major opiate routes coursing through Kazakhstan from Tajikistan. The first starts in Dushanbe, crosses over into Saryasa district in Uzbekistan’s southernmost province of Sukhandarya and continues to the historical Bukhara before reaching Tashkent and crossing the Uzbek- Kazakh border. From Shymkent (Southern Kazakhstan) the drugs flow eastward via the city of Taraz towards Almaty. From there, shipments move towards Karaganda, reaching Astana, then Kokshetau and lastly Petropavlovsk before reaching Russia. The second route mimics the first one until it reaches Bukhara. Illegal merchandise then crosses into Tashavuz (Turkmenistan) before coming back into Uzbekistan at Kungrad. From here, drugs are shipped via rail through Beineu (on the border with Kazakhstan) traversing Northward into Russia. The third route commences in Dushanbe journeying onto Chorjou (Turkmenistan) from Bukhara via Bekdash railway crossing and carrying on northward into Atyrau into Russia.

Azerbaijan60 regularly intercepts drugs coming from Iran. Customs officials declared61 that Azerbaijan seized shipments of heroin which primarily enter the country from Iran. Drug discoveries and seizures from Iran are increasing, including certain consignments concealed and embedded in Iranian trucks as carrying raisins to Moldova.

With a 6800 km-long shared border between Russia and Kazakhstan and hundreds of tonnes of drugs flowing annually, drug trafficking has dire implications beyond the social costs of addiction and directly threatens Russia’s security62. The crime and terrorism nexus operating in the region thus makes Central Asia a hub63 for trafficking and smuggling.

Almaty is a crossroads for opiates and cannabis from southwest Asia linking Central Asia to Russia and Europe. This occurred due to lax customs controls and the city’s prime position as a transportation hub. Large quantities of morphine with a base in Afghanistan are stored in Almaty64. There’s room for smuggling to grow further. The Greater Eurasian Partnership and other Customs Unions linking Kazakhstan with Russia and Belarus, with lax controls along Kazakhstan’s northern border, stimulates smuggling with a majority of drug shipments en route to Russia. The Customs Unions have been abused as traffickers opt to cunningly re-route opiate deliveries to Europe through the northern route, as opposed to the traditional tried-and-tested Balkan route.65

All drugs smuggled via the “northern route” have to transit Kazakhstan (unless they are shipped aerially or across the Caspian Sea).

However, Kazakhstan, due to its ample financial resources, is potentially the best equipped of all Central Asian Republics (CARs) to tackle the trafficking threat66.

There are three smuggling routes crossing Kazakhstan from Kyrgyzstan67 toward Russia. The first trail commences in Bishkek, crossing over the border into Korday (Kazakhstan) towards Almaty and onward to Ayaguz via Georgievka and Ust-Kamenogorsk into Russia. From Bishkek, the second route goes via Almaty onwards through Saryshagan to Petropavlovsk, prior to reaching Russia. The third route courses westward from Bishkek into Taraz via Symkent-Kyzylorda and Uralsk into Russia.

Uzbekistan is where drug trafficking and terror funding intersect. For example, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU ) (with discrete but diminishing training grounds and sanctuaries in Afghanistan) made many terror incursions into Kyrgyzstan. IMU also attacked Uzbekistan with attempts to overthrow the secular government of President Karimov. Entities like IMU also secure drug trafficking routes from Afghanistan. The IMU also stockpiled opium and heroin from Afghanistan following healthy harvest seasons, transporting these illegal substances to Russia and Western Europe68.

From Uzbekistan, two routes transport opiates into Russia- Saryagash then by Shymkent and Taraz. From there, one trail goes through the Shu valley into Karaganda prior to leaving the country through Pavlodar. The second portion of this journey proceeds east into Taldykugan, moving onto Georgievka and Ust-Kamenogorski before crossing into Russia. The third powder trail goes from Uzbekistan, commencing in the capital of Karakalpakstan, Nukus, moving into Beineu and Makat prior to reaching Atyrau and leaving the country via the village of Ganyushkino.

Drug trafficking from Turkmenistan across the northern border into Kazakhstan is also common. This route offers access to northern and western Kazakhstan and facilitates onward trafficking to areas such as Orenburg in Russia. Authorities have thus far initiated comparatively minor seizures in neighbouring Turkmenistan – Atyrau and Mangystau – larger amounts of seizures are documented in Western Kazakhstan of opiates exiting the country. Kazakhstan’s western regions are highly susceptible to trafficking.

Railways connecting Kazakhstan and Russia are deemed essential trafficking conduits for drug trafficking. Major illegal shipments penetrating Kazakhstan by train cross the border areas of Arys and Biney on the borders with Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan respectively. Drug trafficking using vehicles enters the country mostly across the borders in Shymkent, Zhambyl and Almaty provinces. Known exit points on the Kazakh-Russian border are Astrakhan, Orenburg, Omsk, Chelyabinsk and Novosibirsk.

Source: Another powder trail, The Economist.

Source: Another powder trail, The Economist.

Southern Kazakhstan, Almaty City and eastern Kazakhstan are the main spots in Kazakhstan with fairly consistent opiate seizures, representing their centrality to trafficking operations.

Shipments move directly through Kazakhstan although one often mentioned convergence point is the city of Karaganda, which straddles the major route69.

A key entry point for traffickers on the Uzbek-Kazakh border is Shymkent – considered a strategic node for drug trafficking. With a substantial Uzbek population, Shymkent is close to Tashkent and, like Osh, is a central artery in the veins of Central Asian drug trafficking. It has also drawn comparisons with Osh, due to the growth of extremism in the city and the wider region.

Uzbekistan carries on mounting multiple seizures of heroin bound for Kazakhstan and further to Russia, the tally for Kazakhstan and neighbouring Kyrgyzstan is comparatively inadequate.

Other than land routes, the Caspian seaports of Aktau and Atyrau in Kazakhstan are incentivizing smugglers and traffickers in other Caspian coastal countries given the seaports’ integration in extra regional connectivity projects.

Central Asia is not a priority for Brussels but it should be since Afghan heroin and meth trafficking along the Northern and the Balkan route reaches Europe and the Black Sea route through Turkey is a swiftly emerging prominent smuggling corridor70.

India’s Growing Narco-Terrorism

Unlike China, which has now designated over 100 fentanyl variants and precursors on its list of controlled substances, India has not placed fentanyl, or most other opioids, on its controlled substances list, easing production and narcotics export. India only regulates 17 of the 24 basic antecedent chemicals for fentanyl (as stipulated by the UN 1988 Convention against Drugs)71.

Indian tramadol networks are linked to ISIS72 and Boko Haram. U.S. law enforcement officials estimate that 1 billion tramadol tablets have been seized departing India for the U.S and its global partners in anti-narcotics, and actual exports could be exponentially greater, raising security alarm bells.

There have been multiple seizures of tramadol from India destined for Islamic State territory. In May, $75 million73 worth of tramadol, about 37 million pills, were seized in Italy,74 en route to Misrata and Tobruk, Libya. ISIS purchases these opioids for resale to ever-growing markets. The IS terrorists are involved in both the trafficking and consumption of tramadol in large quantities – selling drugs at a substantial profit to bankroll its narco-terrorism activities from ISKP (Khorasan Province, South Asia) to ISIS in Africa and beyond.

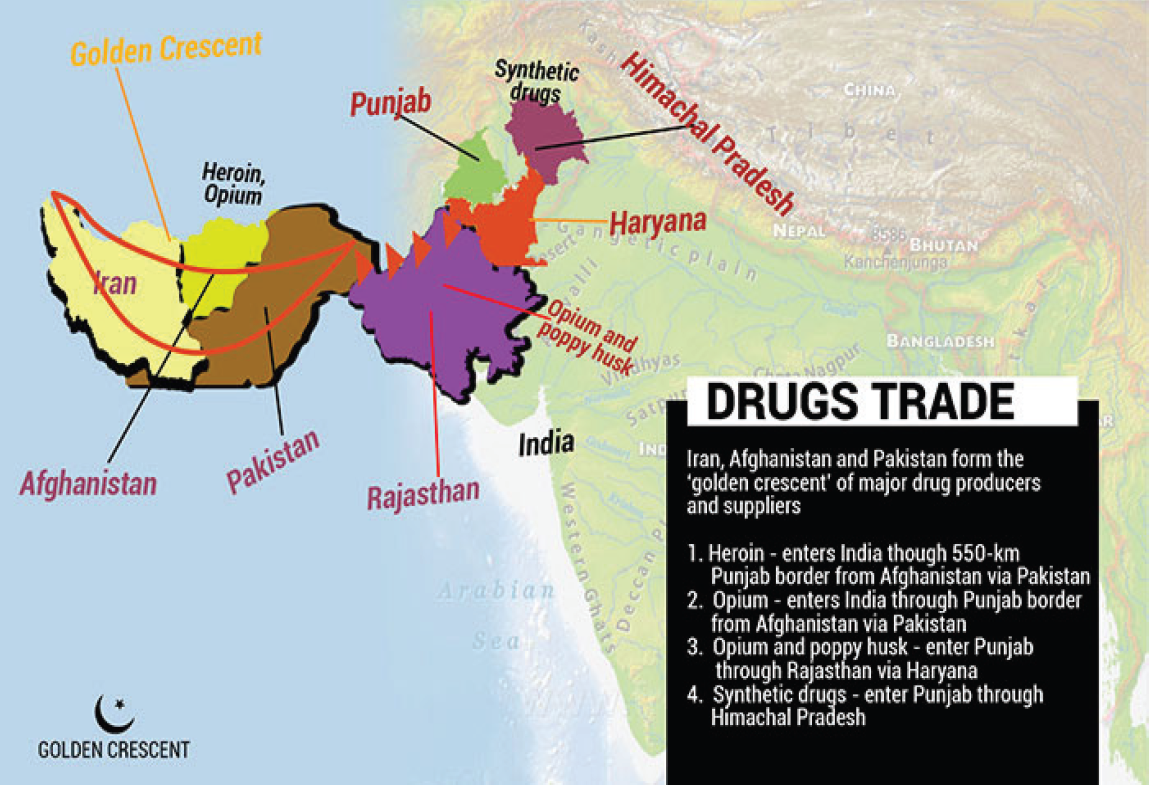

The routes through which Afghanistan’s opiates enter India are highlighted and explained in the detailed infographic below.

Dabas, Maninder (2016) The Golden Crescent – the route through which drugs are making their way into Indian Punjab, India Times, 10 June, 2016.

Dabas, Maninder (2016) The Golden Crescent – the route through which drugs are making their way into Indian Punjab, India Times, 10 June, 2016.

Along the new maritime routes, in September, Indian authorities in Gujarat discovered almost 3 tons of heroin that had been smuggled from Afghanistan and routed through the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas75. Heroin shipments also infiltrate India once it has made its way from Afghanistan to Iran’s port of Chabahar as confirmed by India’s Directorate of Revenue Intelligence (DRI) which routinely gains intelligence that shipments from the Kandla Port in Kutch District of Gujarat or Bandar Abbas Port in Iran (originating in Afghanistan) carry narcotics through to India. Intelligence through the years reveals that these shipments are imported from Iran often by companies in India’s South, including cities like Vijaywada.

Gujarat’s Anti-Terrorist Squad (ATS) confirm that Gujarat’s coast is a transit route for mafias to smuggle drugs into India from Iran and Afghanistan.

Iran’s growing narcotics menace

The 3 April poppy ban does not, however, imply that the Taliban have totally taken their eyes off lucrative Western and European markets. On the contrary, the long-term goal seems to be covertly moving toward centralization of the narcotics industry into the government’s broader networks and ultimately revenue maximization flowing from that industry into state coffers.

As an insurgent group, the Taliban had hardly any choice but to work with local drug distributors and regional smugglers focusing on the heavily patrolled Iranian border as the most practical route to deliver tons of heroin, opium and meth to high-paying European markets. Under mounting security and law enforcement pressure within Afghanistan and along the sensitive border with Iran, the Taliban-backed traffickers occasionally went as far as to rely on equipment that catapulted drug consignments across the Iranian border or on heavily drugged unmanned cattle plodding non-suspiciously into Iran76.

In December 2021, police in southeast Iran reported that over 103 tons of drugs were seized in 8 months, while over 14 tons of narcotics were intercepted in Bushehr province over the past 9 months, representing a 25 percent increase from the same period in 2020-

1. Iranian law enforcement authorities are actively identifying and dismantling drug-smuggling groups, especially in Zahedan, Sistan and Balūchestān provinces in southeastern Iran, which are notorious hubs for trafficking and smuggling.

Being a neighbor to the biggest producer of drugs in the world (Afghanistan) has caused Iran to shoulder a heavy burden as one of the main routes for drug transport.

Though Iran spent more than $700 million on sealing its borders and preventing the transit of narcotics destined for European, Arab, and Central Asian countries77, few mistakenly believe the various border walls and fences constructed between Iran and Afghanistan will contain the flow of lethal drug supply chains. There are ample gaps78 within such structures, corruption and tentative routes (encompassing catapults) that allow large numbers of people and drugs to pass through. The drugs trade is irreversibly cross-border, trans-national and global in nature.

Source: Drug smuggling (2021) Potential catapult site, Iran-Afghanistan border, Iran-Afghanistan border.

Source: Drug smuggling (2021) Potential catapult site, Iran-Afghanistan border, Iran-Afghanistan border.

Iranian smugglers are increasingly opting for maritime routes for trafficking. In December 2021, the US Navy seized 385 kg heroin and arrested Iranians on a vessel in the Arabian Sea that came from Iran. Earlier in the month large amounts of meth and heroin were found while rescuing Iranian sailors from a burning vessel in the Gulf of Oman. The Arabian Sea and Gulf of Oman are increasingly being used as drug conduits.

Narcotics illicitly permeate from Afghanistan into Iran and Pakistan through Zahedan, city and capital of Sistan in Balūchestān province, southeastern Iran, near the borders of Afghanistan and Pakistan.

All along the ‘Balkan Route’, narcotic seizures are through the roof. Iran regularly intercepts tons of opium, meth and hashish in the southeastern town of Zahedan.

From Afghanistan to Iran, many lethal substances are destined for Western Europe; from Iran via Azerbaijan, Georgia and Ukraine (less so since Russia’s invasion). Iranian and Azeri organized-crime narcotics networks are highly involved, these are the networks who dominate the Balkans route for Afghan opiates.

Very large seizures over the past few years imply that the Caucasus and the wider Black Sea region are playing an increasingly instrumental role as a route and conduit for heroin originating from Afghanistan. Despite Western European law-enforcement assertions to the contrary, the Black Sea route is resurfacing as a prominent corridor for processing heroin and shipping it to Western Europe and Russia79.

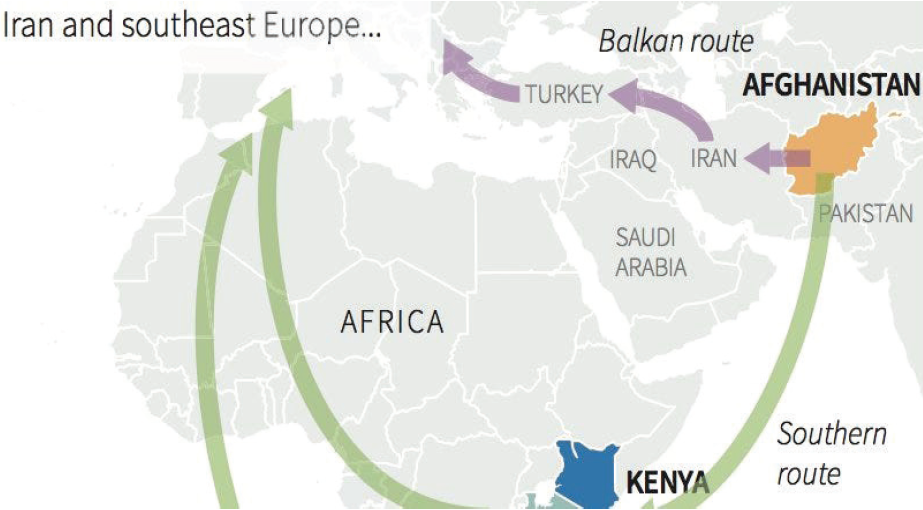

Sterbenz, Christina (2015) Here`s how Afghanistan`s record opium harvest is flowing to the West through Iran and Southeast Europe, Business Insider, 8 March, 2015.

Sterbenz, Christina (2015) Here`s how Afghanistan`s record opium harvest is flowing to the West through Iran and Southeast Europe, Business Insider, 8 March, 2015.

It is also unsurprising that the Taliban government currently has initiated draconian procedures to crack down on opiate addiction in society and regulate demand and supply domestically. The emerging status quo has grave implications for Iran, which has conventionally acted as a key transit route for Afghanistan-sourced global drug trade. Tehran has, unlike Kabul, refrained from using narcotics as a state instrument of revenue generation or a strategic source of leverage against the West.

The Trump administration’s “maximum pressure campaign” against Iran threatened to subvert Iran’s narcotics policy. In July 2018, shortly after President Donald Trump’s administration pulled out of the JCPOA (Iran nuclear deal) and reinstituted wide-ranging sanctions against Tehran, Iranian Interior Minister Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli80 confirmed the growth of drug production in Afghanistan to over 9,000 tons per annum and warned that if Tehran “looked the other way, over 5,000 tons of narcotics would leave Iran’s borders for the West.”

Iran did not end up making a major policy shift for a variety of political and practical calculations81, including the Iranian government’s profound interest in conserving the reputational gains of a well- functioning rapport with the U.N. on counter-narcotics.

Tehran faces intense pressure on its borders due to illicit narcotics penetration, however, it is no longer the most essential regional gatekeeper for Afghanistan’s narcotics trade into Europe. That role now largely falls on Turkey’s82 shoulders.

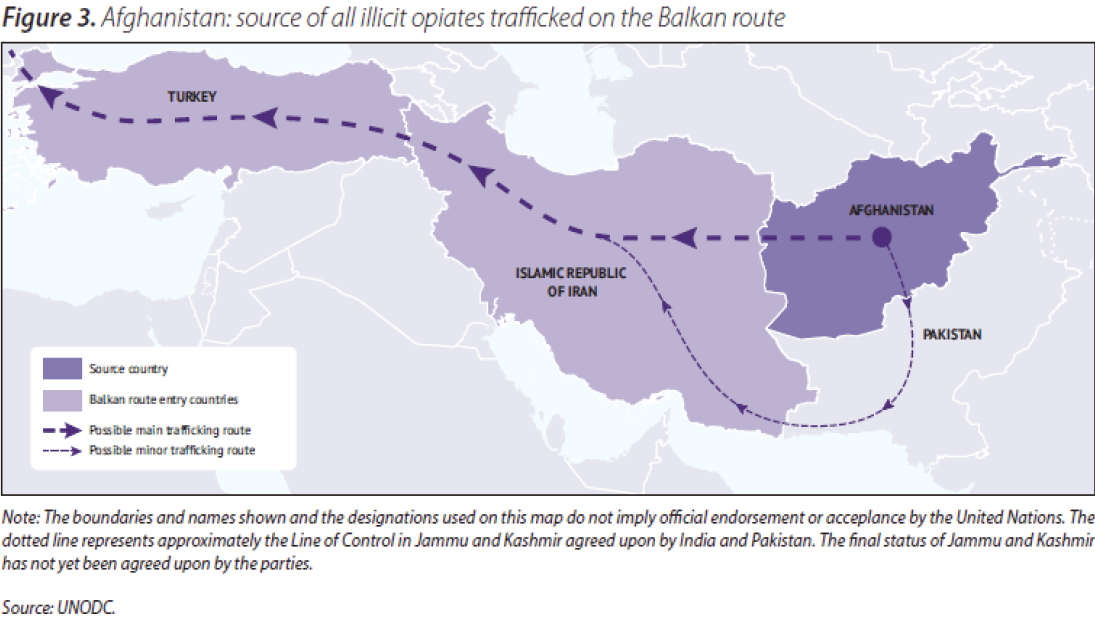

Turkey’s cross-border drug challenges

Afghan narcotics are trafficked into Turkey mostly through the Balkan route (trafficking route from Afghanistan to Iran into Turkey). The Balkan route has traditionally been the primary route for trafficking heroin out of Afghanistan, especially via the Turkey-Iran land borders (the Gurbulak – Bazargan and Dogubayazit – Tabriz border crossings).

Afghan drugs also enter Turkey through Georgia (via the Sarpi border crossing on the Black Sea coast usually emanating from Batumi and Hopa) and, to a lesser extent, Syria (Southeast of Anatolia, Turkey, has five provinces straddling the border with Syria: Hatay, Gaziantep, Kilis, Mardin and Şanlıurfa via the Bab al-Hawa Border Crossings (“Gate of the Winds”) the international Syria-Turkey border between the cities of İskenderun and Idlib).

Afghan opiates and heroin also worm their way into Turkey through multiple seaports along the Mediterranean, the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara.

Source: Crabtree, Ben (2020) Black Sea – a rising tide of illicit business. The Black Sea region may be experiencing a resurgence in the trafficking of Afghan heroin. Global Initiative against transnational organized crime, 1 April, 2020.

Source: Crabtree, Ben (2020) Black Sea – a rising tide of illicit business. The Black Sea region may be experiencing a resurgence in the trafficking of Afghan heroin. Global Initiative against transnational organized crime, 1 April, 2020.

Formally, the Turkish National Police (TNP) Department of Fighting Against Drugs, the Gendarmes, and the Turkish Coast Guard are responsible for combating against the supply side of drug trafficking83. The Ministry of Finance is tasked with money laundering investigations involving contraband and drugs.

Launched in 2018, Turkey’s National Strategy and Action to Combat Illegal Drugs84 (2018-2023) is the country’s fifth official strategic drug policy document. The action plan is based on the twin pillars of drug supply and demand reduction respectively85.

Turkey’s interest in narcotics augmented substantially during the course of the protracted Syrian civil war86, where opiates were heavily consumed by front-line soldiers engaging in close combat. During the civil war, Turkey supported an unconventional constellation of militants and paramilitary entities in Syria, which gradually needed to mature an indigenous economy of their own to bankroll their war initiative. These groups resorted to illicit business in fuel and narcotics smuggling.

Turkey’s close control and monitoring of Afghanistan’s outbound opiate supply lines offer it an additional advantage: it gives Turkey a strategic lever of influence for future talks on Turkey’s inclusion in the EU, it also brings influence to bear for Ankara over European rivals in times of heightened crisis, as was the case with Ankara’s stance regarding Syrian war refugees and migration flows. “We believe that some [Afghan methamphetamine87] has gone to Turkey,”88 stated an analyst. “And if it reaches Turkey, then we assume that some will get to Europe.”

Drug seizures in Turkey increased in 2021 as per the Turkish ministry of interior89. In 2021 Turkish security forces conducted 215,000 anti-drug operations across the country. Nearly 294,000 people were detained in those crackdowns and over 26,000 suspects were arrested and drug-related deaths were down by approximately 9 % in 2021.

Security forces seized some 58,000 tons of marijuana, 5,300 tons of skunk, 20,500 tons of heroin, 614 tons of cocaine and 4,800 tons of methamphetamine as well as nearly 6 million ecstasy pills.

The ministry also noted that directives were sent to the governor’s offices in the country’s 81 provinces seeking cooperation in demolishing or rehabilitating idle buildings where drug use occurs90.

Turkey’s Interior Ministry also confirmed that more than 11,200 drug awareness events were organized, and officials reached 449,000 mothers and expectant mothers as part of the programs designed to raise awareness against drug use.

Source: UNODC (2021)

Source: UNODC (2021)

Source: Task and Purpose (2018) the U.S spent USD 8.6 billion fighting the Afghan drug trade and failed miserably.

Source: Task and Purpose (2018) the U.S spent USD 8.6 billion fighting the Afghan drug trade and failed miserably.

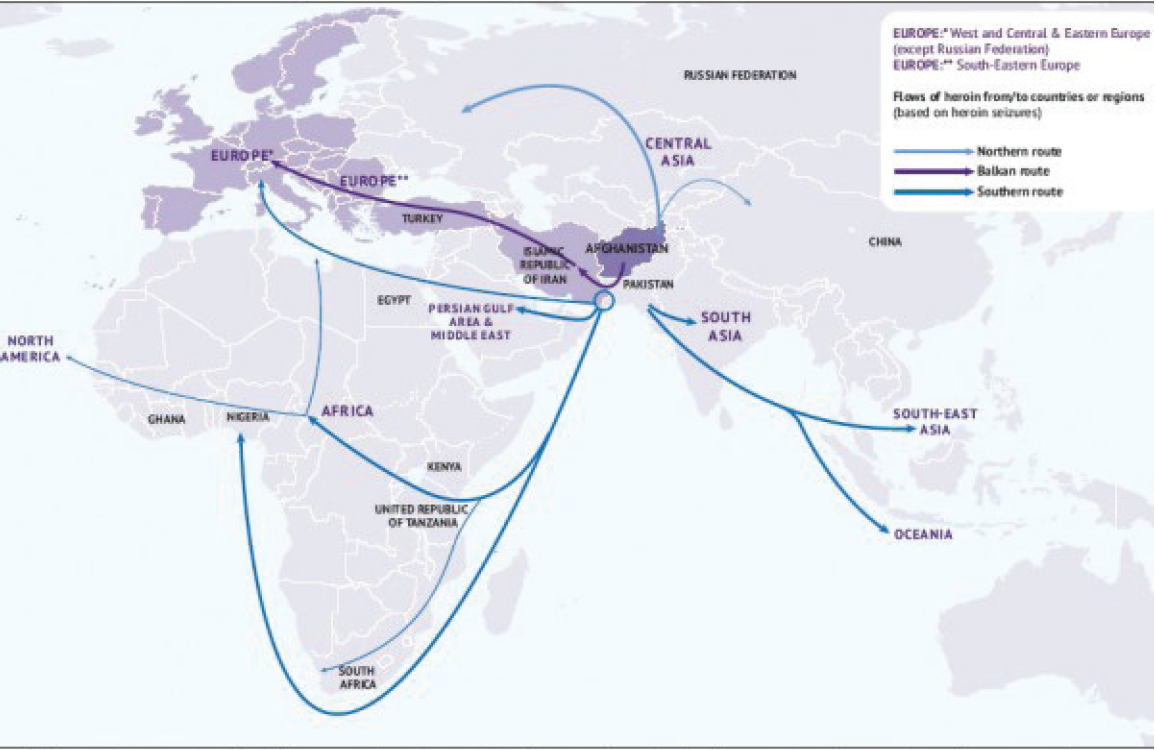

Trafficking continues along various long-established smuggling routes: the ‘Balkan Route’, courses through Iran and Turkey. The Balkan Route (view the figures and maps below) is a crucial path for the delivery and distribution of opiates from Afghanistan into Western and Central Europe through the Balkan states of South-Eastern Europe.

The Balkan Route transfers illicit drugs from Afghanistan to Iran through to Turkey onto the Black Sea routes (including Istanbul) into Bulgaria and onto Western and Central Europe’s hinterland. An alternative Balkan route is also from Afghanistan to Iran to Azerbaijan over to Georgia, often leveraging the Georgian ports of Poti and Batumi over the maritime Black Sea, into either Bulgaria’s port cities of Burgas and Varna or Romania’s Constanta or Ukraine’s port cities of Odessa, Sevastopol and Mariupol91 (blocked since the Russia Ukraine war).

A UNODC research estimates that the total monetary value of illicit opiates trafficked along the Balkan route is estimated to be USD 28 billion per annum.

Source: Routes of heroine flows through the Black Sea Region (2021) Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime

Source: Routes of heroine flows through the Black Sea Region (2021) Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime

The next major narcotics route is termed the ‘Northern Route’, which goes from Afghanistan through either Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan in Central Asia over to Russia or Pakistan into China and beyond.

Source: Supply routes from Afghanistan to Russia (2021) Stratfor.

Source: Supply routes from Afghanistan to Russia (2021) Stratfor.

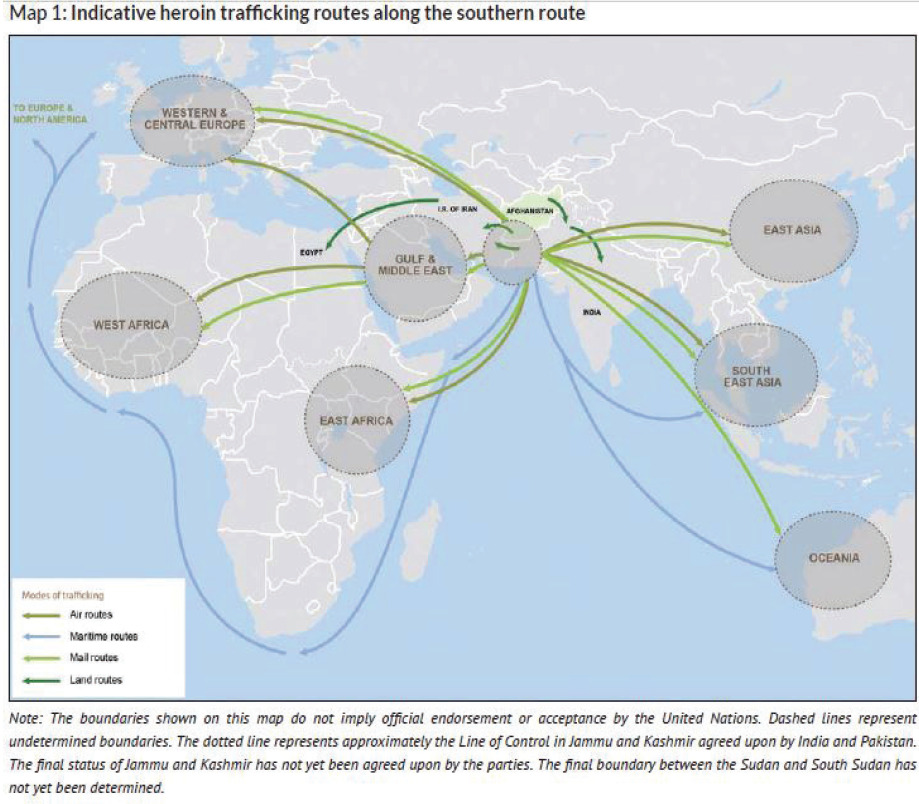

Finally there is the ‘Southern Route’.92 (view below for details) coursing through Pakistan and the Indian Ocean to Africa.

Source: Indicative Heroin trafficking along the Southern Route (2021) by the UNODC`s Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS) as well as the Annual Report Questionnaire (ARQ).

Source: Indicative Heroin trafficking along the Southern Route (2021) by the UNODC`s Drug Monitoring Platform (DMP) and Individual Drug Seizures (IDS) as well as the Annual Report Questionnaire (ARQ).

Future recommendations

A unremittingly creative and flexible narcotics market, with innumerable methods to hide and smuggle drugs each year, illustrates that the illicit drug trade is a transnational challenge requiring innovative out-of-the-box solutions and concentrated cooperation between all affected states.

Drug trafficking, smuggling and consumption are complex cross- border issues that must be combated on multiple fronts. South Asia’s drug policy must encompass a broader concept of security that integrates the region. Intense regional cooperation is mandatory, as is stricter region- wide border policing and law enforcement.

Drug addiction coupled with a growing regional HIV crisis (due to dirty needles being exchanged when addicts shoot up heroin and other drugs) will touch endemic levels in the future if it continues to be swept under the carpet. Demonizing and dehumanizing users implies that addicts will not seek treatment and will remain alienated and marginalized.

Criminalization of addicts has not and will not reduce the demand for drugs. Better long-term treatment and harm (self-abuse) reductions services are required, especially in jurisdictions where opioid substitution therapy remains forbidden93.

Nurturing more humane counter-narcotics policies seems, at the moment, more feasible than tackling the systemic causes of the drug trade in South and Central Asia. The latter requires a robust long- term strategy that transcends anti-drug operations and border control. Regional actors must step up their cooperation both at home and abroad.

A practical and actionable policy in Afghanistan would not prioritize but would mount a multi-pronged attack, integrating: intensive stealth diplomacy; a reshaped more inclusive military and intelligence strategy; urgent police94, judicial, and economic reforms; and key performance indicator based targeted development initiatives.

Instead of nation building, the “drugs epidemic” firstly requires region building where Pakistan has already (and must carry on) taken the lead in revitalizing the international community’s strategy towards Afghanistan. The recent 2022 OIC conference in Islamabad pledging humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan is an instructive case in point.

Region-building must integrate counter-terrorism with counter- narcotics as both are inexorably wedded to one another. Region-building can be further intensified through regional entities and fora such as the Russian led Greater Eurasian Partnership (GEP), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO)95. The Sino-Russian led SCO’s 2018-2023 anti-drug strategy births the creation of an efficient anti- drug protocol within the organization. It must be extended, amplified and complemented with full support from the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB).

The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO)96 the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO)97 military alliance, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC)98 and the Central Asian Regional Information and Coordination Center (CARICC) can be used for tackling illicit narcotics trafficking.

The anti-narcotics potential of regional organisations such as those mentioned can be better coordinated and have not been fully exploited as they are limited in terms of capacity and political will. Until the political will and capital is leveraged and deepened there can be only short-term solutions to a much more endemic challenge. More cooperation with the EU (deeply affected by the drug trade) is also the need of the hour.

More co-operation amongst all the above with a view to deeper collective intelligence-sharing on narcotics, capacity-building, centralizing database repositories, knowledge workshops, carrying out joint interdictions, raids and forensic testing of narcotics seizures and documenting and automating drug seizure operations conducted collectively is required. The largest drug smugglers and traffickers should be added to the Global Terrorist Database (GTD) as this research has proven the nexus between narcotics, terrorism and transnational threats.

All this, with key buy-in from the Taliban, the EU, US and UN, can lead to more earnest results. Such a dynamic, consultative, integrated approach to anti-narcotics will go a long way in realistically containing illicit funds and substances world-wide.

Multifaceted roles and cross-cutting anti-narcotics mandates of various national stakeholders can be leveraged as a force-multiplier to mitigate and contain the perils and challenges of drug trafficking in South and Central Asia.

Given the intensely mounting insecurity, demand reduction measures in Afghanistan, like treatment and prevention, have for years been the most promising and constructive medium for drug policy interventions. However, such treatment and prevention measures were never substantively funded or prioritized, either by international donors or the Afghan government. The time is ripe to rethink drug policy intervention funding modalities in South Asia.

Another major challenge will be winning back the “hearts and minds” of Afghan citizens, especially villagers whose lives and livelihoods have been devastated by the drug trade, crippling poverty, drought, Covid-19 and non-ending economic woes with ripple effects for Pakistan and the region.

Farmers, communities and traders need to be incentivized to start micro-enterprises (Bangladesh model) and to switch to alternate subsidized Afghan cash crops like profitable pomegranate trees, aloe vera, saffron, wheat, rice, maize, barley and cotton. Economically engaging more Afghans with lucrative mining, especially lithium, over the medium to long term, are steps in the right direction.

The global community should initiate endeavours to devise legal alternatives and “regulated financial networks”. More specifically, it should deepen assistance to the Afghan government by building a farm support network via funding rural development programs (such as those achieved by the Agha Khan Rural Support Program and the Rural Support Programmes Network in Pakistan) enhancing Afghan farmers’ access and connectivity to regional markets and subsidizing legal crops.

Certain analysts observe that totally stamping out the drug trade will make the Afghan economy too fragile. That might be true in the short run and is something the donor and diplomatic corps should accommodate. However, once drugs are substituted with legal commerce, the total opposite is true.

For millions of rural Afghans, the greatest perceived threat is economic instability, not drugs per se. The recommendations in this CQ report will require international aid and donor assistance, which is contingent upon an international recognition of the Taliban government which does not seem imminent in the near future. This catch-22 dilemma will remain a constraining conundrum.

References

- Mansfield, David (2022) Drugs and departures: coping with the economic collapse in Afghanistan. Alcis, January 4, 2022.

- ISSI Islamabad (2022) CAMEA (ISSI) FES International Conference, Working Session 1, “Perspectives on the Evolving Situation in Afghanistan”, Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad (ISSI) and the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES), 28 March, 2022.

- 97 percent of Afghans could plunge into poverty by mid-2022, 9 September, 2021, United Nations Development Project (UNDP), 2021.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2019). Opiate Trafficking. For access https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/AOTP/UNODC_AOTP_VOL3_BALKANS_2020_web.pdf

- U.S. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan (SIGAR) report, May 2021.

- The Newspaper’s (2022(-02-07). “Five soldiers martyred as Afghan-based terrorists target post in Kurram”. 7 February, 2022, Dawn.

- As per the UNODC`s 2022 report on opium, Helmand still remains the country’s major opium poppy cultivating province at 109,778 hectares, followed by Kandahar (16,971 hectares) and Farah (11,461 hectares). Alarmingly, the number of poppy-free provinces in Afghanistan decreased from 12 to 11 in 2021 under Taliban rule.

- Whitlock, Craig (2019) Overwhelmed by opium – the U.S. war on drugs in Afghanistan has imploded at nearly every turn, Washington Post, 9 December, 2019.

- Felbab-Brown, Vanda (2021) The Taliban and drugs from the 1990s into its New Regime, Small Wars Journal, 15 September, 2021.

- The Taliban’s poppy ban redux (2022), Global Initiative against transnational organized crime, 13 April, 2022.

- Opiate examples include the highly addictive heroin, morphine (a pain- killer), codeine, hydromorphone, oxycodone (OxyContin), meperidine, diphenoxylate, hydrocodone (Vicodin), fentanyl (which is a synthetic opioid pain reliever) and propoxyphene. Synthetic versions are also abundant. Each opiate ranges in potency and ability to bind in the brain. For more on addictive pain-killers: Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, Davies MC (2013) Associations of Nonmedical Pain Reliever Use and Initiation of Heroin Use in the United States. CBHSQ Data Review SAMHSA. August 2013.

- According to the Research and Trend Analysis Branch, of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC hereafter) (2022) Afghanistan Opium Survey 2021, Cultivation and Production, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, March 2022.

- Martyr, Kate (2021) Afghanistan opium trade booms since Taliban takeover, DW, 2021.

- Dawi, Akmal (2022) Explaining U.S sanctions against Taliban, Voice of America, 5 February, 2022.

- U.S. Treasury Issues General License to Facilitate Economic Activity in Afghanistan, press release by the U.S Department of the Treasury, 25 February, 2022.

- Ahmadi, Belquis and Asma Ebadi (2022) Taliban`s ban on girl`s education in Afghanistan, United States Institute of Peace, 1 April, 2022.

- Aslam, Azlan (2022) an official at the Excise, Taxation and Narcotics Control Department in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province. TRT World. January, 2022.

- Stone, Rupert (2021) “Business as usual’: Afghan drug trade continues under Taliban, TRT, November, 2021.

- Felbab-Brown, Vanda (2022) Director of the Initiative on Non-state Armed Actors at the Brookings Institution.

- Watkins, Andrew (2020) Taliban fragmentation – fact, fiction and future, United States Institute of Peace, Number 160, March, 2020.

- Felbab-Brown, Vanda (2021) Order from chaos, Will the Taliban regime survive? Brookings, August 31, 2021.

- Sareen, Sushant (2021) Apocalypse Afghanistan, Observer Research Foundation, 3 July, 2021.

- Berry, A Philip (2021) what is the future of UK drugs policy for Afghanistan? RUSI News brief, Volume 41, Issue 7, 10 September, 2021.

- Kilmer B, Everingham S, Caulkins JP et al. (2014) What America’s Users Spend on Illicit Drugs: 2000-2010 RAND Report RR-534-ONDCP. Santa Monica, CA: 2014.

- Horowitz J. (2001) Should the DEA’s STRIDE data be used for economic analyses of markets for illegal drugs? Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001; 96: pp. 1253–1261.

- Graeme Smith and David Mansfield (2021) “The Taliban Have Claimed Afghanistan’s Real Economic Prize.” New York Times. 18 August 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/18/opinion/taliban-afghanistan-economy.html https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/18/opinion/taliban-afghanistan-economy.html

- Northern Afghan provinces submit to lure of opium poppies (2017) France 24, 1 December, 2017.

- Dave D. (2006) The effects of cocaine and heroin price on drug-related emergency department visits. Journal of Health Economics. 2006; 25: pp. 310–334 and Gallet C. (2014) Can price get the monkey off our back? A meta- analysis of illicit drug demand. Health Economics. 2014; 23: pp 54–69.

- French M, Taylor D and Bluthenthal R. (2006) Price elasticity of demand for malt liquor beer: findings from a US pilot study. Social Science & Medicine. 2006; 62: pp. 2100–2112.

- Jofre-Bonet M, and Petry N (2008) Trading apples for oranges? Results of an experiment on the effects of heroin and cocaine price changes on addicts’ polydrug use. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 2008; 66: pp. 279–312.

- Office of National Drug Control Policy (2012) What America’s Users Spend on Illegal Drugs, 2000-2006. Executive Office of the President; Washington, DC: 2012